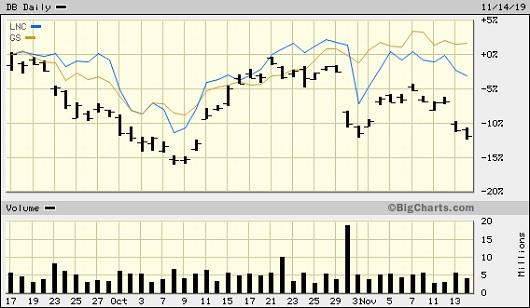

Stock Price of Deutsche Bank, Lincoln Financial and Goldman Sachs Since September 17, 2019 When the Fed Began Pumping Money Into Wall Street

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 15, 2019 ~

Yesterday, for the second day in a row, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, gave testimony and took questions before a Congressional Committee. On Wednesday it was the Joint Economic Committee; yesterday it was the House Budget Committee. On both days, only one member of the Committee dared to ask a question about the hundreds of billions of dollars the Fed is hurling at Wall Street each week in repo loans.

The crisis in the repo loan market, where financial institutions make overnight loans to each other, began on September 17 when the interest rate spiked from the typical range of 2 percent to 10 percent. For the first time since the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve had to step in with lots of cash to ease the liquidity stresses. The Fed has continued to offer that cash every business day since that time and is now supplementing its overnight loans, which can run as high as $120 billion per day, with $35 billion in 14-day term loans twice a week. In total, the Fed is offering $670 billion each week in revolving loans to securities firms it will not name for a crisis it cannot define.

It’s seems to be only Republicans from Texas who have the guts to confront the issue when Powell appears before Congress. On Wednesday it was Congressman Kenny Marchant who questioned Powell on the issue; yesterday it was Congressman Bill Flores, another Republican from Texas, who raised the subject. Here’s how the exchange went yesterday:

Flores: “The Federal Reserve had engaged in some substantial repurchase market activities beginning in mid September and then the Fed was actively involved earlier this week. Can you tell us what’s causing the liquidity issues that are causing the Fed to intervene. You said they’re technical and I’m not disputing that but I’m just wondering can you tell us what’s underneath that, that’s causing that activity.”

Powell: “I want to stress that these are not things that will affect economic outcomes.”

Flores: “Right, I’m not implying that. I think you’re trying to do the right thing, I just need to know what’s causing it, underlying.”

Powell: “So one big thing is we’ve been allowing the balance sheet to decline in size and we stopped that process back in July. Really it comes down to the supply of reserves, which are something that we create. We surveyed all the banks and said what’s your lowest comfortable level of reserves. We added that up, we put a buffer on top of it and we felt we were probably well above the level of scarcity. And then in early September we had a situation where the liquidity – where banks had much more liquidity than they said they needed and yet it didn’t flow into the repo market.”

Let’s pause right here for a moment. Asking the mega banks on Wall Street, which blew themselves up in 2008 because they would much rather gamble in high risk derivatives and convoluted investment products with their depositors’ money, how much they would be comfortable holding in liquid reserves at the Fed is like giving a four-year old the choice between a pony or a book for Christmas. Naturally the Wall Street banks are going to want to yank as much liquidity as they can get from the Fed to enrich their trading books. And since when does the regulator of the most serially charged bank holding companies in America seek the opinion of the serially-charged miscreants?

As an example of what we mean, JPMorgan Chase was found by the U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations to have used its bank depositors’ money to make hundreds of billions of dollars of high-risk wagers in derivatives in London in 2012 and lose $6.2 billion. The Subcommittee found that JPMorgan Chase “piled on risk, hid losses, disregarded risk limits, manipulated risk models, dodged oversight, and misinformed the public.” And now the Fed is going to ask the same bank how much liquidity it would like to keep locked up at the Fed and not have available to trade (read “gamble”) with? JPMorgan Chase proceeded to pull $145 billion from its reserves at the Fed. On October 15, during an earnings call with analysts, JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said the bank has just $120 billion now in reserves at the Fed and that amount wasn’t enough to allow it to assist in the repo loan market on September 17 and still meet its regulatory requirements for keeping adequate liquid reserves on hand for an emergency.

Throughout Powell’s exchange with Congressman Flores he appeared nervous and fidgety and was waving his hands around. This is not Powell’s normal behavior under questioning in Congress. We found out why when Powell appeared to admit that the Fed is not completely confident that it understands “why” the liquidity crisis is happening.

Powell: “We’re doing a lot of forensic work to understand why. Some of that may be reserves – the level of reserves needs to be higher than we thought, which means our balance sheet a little bigger. There may also be aspects of our supervisory and regulatory practice that we can look at that would allow the liquidity that we have, that we think is the appropriate level, to flow more freely in the system. Without, though, undermining safety and soundness.”

Perhaps if Chairman Powell had been sitting at a trading desk on Wall Street on October 19, 1987 he would be able to come up with a far more realistic assessment of what stopped the mega banks on Wall Street from jumping at the opportunity to make loans at 10 percent on September 17. It’s called “backing away” and it’s what Wall Street trading houses (which now own federally-insured commercial banks) do when they are not sure about which of their counterparties might have a money problem. On October 19, 1987, as the Dow Jones Industrial Average proceeded to plunge by 508 points (22.6 percent in one day), some Wall Street trading houses simply stopped answering their phones because they did not want to be on the hook for a losing trade or engage in trading with counterparties who might not be around the next day because they had suffered enormous losses.

All one needs to look at is the stock price chart of Deutsche Bank to figure out what counterparty Wall Street is worried about today. Deutsche Bank is tied to Wall Street and other global banks as a derivatives counterparty – to the tune of tens of trillions of dollars in notional (face amount) of derivatives. And while other big Wall Street bank stocks have rallied since the Fed began pumping hundreds of billions of dollars a week into Wall Street, Deutsche Bank has not. Two other firms which have not rallied are Goldman Sachs and Lincoln Financial – also heavily exposed to derivatives. (See chart above.)

Chairman Powell might do himself and the country a big favor by carefully reading a February 2015 report from the federal agency created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation to alert regulators like the Fed to rising financial stability dangers. That’s the Office of Financial Research (OFR) and this is what its researchers said in that report:

“The larger the bank, the greater the potential spillover if it defaults; the higher its leverage, the more prone it is to default under stress; and the greater its connectivity index, the greater is the share of the default that cascades onto the banking system. The product of these three factors provides an overall measure of the contagion risk that the bank poses for the financial system. Five of the U.S. banks had particularly high contagion index values — Citigroup, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Goldman Sachs.”

Powell could further expedite his forensic work by reading the 2016 report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). That report found that Deutsche Bank is heavily interconnected as a financial counterparty to JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America as well as to big European banks. The IMF researchers found that Deutsche Bank posed a greater threat to global financial stability than any other bank as a result of these interconnections.