By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 7, 2019 ~

One or more U.S. or foreign banks that are primary dealers to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is in need of longer-term loans that they are unable to get anywhere else – at least at an affordable rate of interest. That’s the only reasonable conclusion that can be drawn from the Fed’s announcement on Friday that it is extending its money pumping program to Wall Street until at least November 4 and will be offering an additional $310 billion cumulatively in term loans (most for 14-days at a time) as well as offering at least $75 billion daily in overnight loans.

The Fed’s money sluicing operation that began abruptly on September 17 is taking on the distinct appearance of its machinations during the early days of the 2008 crash – a time when it also refused to name the banks that were receiving the money until a multi-year court battle and congressional legislation forced its hand.

The open money spigot at the Fed comes at a time when global banks, including many that are among the Fed’s 24 primary dealer banks that are able to borrow from the New York Fed under its current repo (repurchase agreement) operations, have announced large job cuts. The most recent news came from the Financial Times over the weekend in a report that says HSBC is planning another 10,000 job cuts on top of the 4,700 it had previously announced.

Another European bank that is heavily interlinked via derivatives with Wall Street, Germany’s biggest lender, Deutsche Bank, has seen its stock set new historic lows all year. (See Lordy, Deutsche Bank Is Having a Helluva Bad Month.) In July, it confirmed plans to cut 18,000 jobs.

According to a chart published by Bloomberg News on September 24, job cuts planned by global banks at that point tallied up to 58,200. That was before the Financial Times reported this past weekend another 10,000 job cuts at HSBC. Securities units at both HSBC and Deutsche Bank are among the Fed’s primary dealers that are eligible to participate in its current repo loan program.

A major U.S. bank, Citigroup, is also culling hundreds of employees in its fixed income and stock-trading operations, according to a July 31 report in Fortune. The publication explained at the time that “Trading revenue at the five biggest U.S. banks on Wall Street dropped 8% in the second quarter, following a 14% slide in the first three months of the year — setting up global banks for their worst first half in more than a decade.”

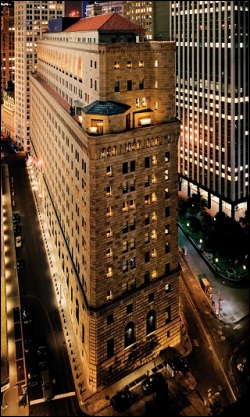

The loans currently being pumped out to Wall Street by the New York Fed (the most powerful of the Federal Reserve’s 12 regional banks) are being offered only to its primary dealers. What most Americans don’t realize is that a large number of these primary dealers are the securities units of foreign banks. (See primary dealer list below.)

The primary dealers not only conduct open market operations with the New York Fed but they must also agree to be contractually bound to make purchases in every auction of U.S. Treasuries. Before the U.S. Department of Justice went into a multi-decade hibernation on the issue of anti-trust and allowed mega banks to buy up other mega banks and thereby become too-big-to-fail, there were 46 primary dealers in 1988. By 1999, that number had shrunk to 30. Today, it stands at 24.

The New York Fed must be desperate to boost its number of primary dealers because in May of this year it added a tiny brokerage firm to its roster, Amherst Pierpont, that pretty much no one outside of Wall Street has ever heard of, and possibly not even there. According to the firm’s website, it has “more than 200 employees.” The big Wall Street banks like JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Bank of America have over 200,000 employees.

The Fed’s money pumping operation today is reminiscent of the controversial program it set up in 2008 known as Single Tranche Open Market Operations or ST OMO. The name was cleverly designed to make it sound like part of the New York Fed’s routine open market operations when it was actually a massive bail out program to teetering Wall Street investment banks that the Fed refused for years to name. On July 7, 2011, Bloomberg News, following a Freedom of Information Act request, reported that Lehman Brothers “borrowed as much as $18 billion in four separate loans…three months before its parent filed the biggest bankruptcy in U.S. history.”

While today’s New York Fed operation is making 14-day term loans, the ST OMO program made 28-day term loans. In a paper published by Levy Economics Institute in March 2013 titled “How the Fed Reanimated Wall Street: The Low and Extended Lending Rates that Revived the Big Banks,” Nicola Matthews explained how ST OMO worked:

“The Single-Tranche Open Market Operations (ST OMO) was implemented shortly after the TAF as a temporary measure to address the continuing risks within the financial markets, specifically the repurchase agreement market or repo and was designed to support primary dealers. The Fed engaged in a series of term repurchasing transactions that spanned from March 2008 to December 2008, approximately nine months with a total of 375 transactions. Along with the TSLF, these operations would contain some of the lowest interest rates for individual banks in the course of the Fed’s response to the crisis. However, the overall mean would be higher than the TAF at 1.93 percent…

“Nineteen primary dealers participated in the ST OMO. The top eight borrowers, comprising 87 percent of the cumulative total with $745 billion, would have a slightly lower borrowing rate from the total average with 1.8 percent. After reaching a peak in October at 3.51 percent, the rates began to decrease dramatically, with two investment banks, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, receiving a rate as low as .01 percent in December 2008 for $50 million and $200 million, respectively. The top three cumulative borrowers, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, and BNP Paribas, would borrow roughly $457 billion at a combined average rate of 1.8 percent.”

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) was forced to perform an audit of the Fed’s crisis era lending programs to Wall Street and global banks as a result of an amendment tacked onto the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation by Senator Bernie Sanders. When the GAO released its audit report in July 2011, it didn’t include monies loaned under the ST OMO. The report stated simply this in a footnote:

“In addition, this report does not cover the single-tranche term repurchase agreements conducted by FRBNY [Federal Reserve Bank of New York] in 2008. FRBNY conducted these repurchase agreements with primary dealers through an auction process under its statutory authority for conducting temporary open market operations.”

According to our sources, the New York Fed is using the same strategy today to deny Congress the names of the banks receiving these hundreds of billions of dollars in revolving loans. Its position is that these loans are not being made as “emergency” loans under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (which under Dodd-Frank clearly requires full disclosure to the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee) but are just plain ole vanilla open market operations that routinely happen all the time. The problem with that position is that this is the first time the Fed has intervened in this manner since the financial crisis of 2007-2008, so it would certainly appear that there is some kind of “emergency” taking place.

It was one of Wall Street’s go-to lawyers, Rodge Cohen of Sullivan & Cromwell, who influenced how the New York Fed would interpret the use of Section 13(3) during the financial crisis. In a preliminary draft report issued by the FCIC, it mentions the involvement of Rodgin Cohen in a Section 13(3) amendment as follows: (The reference to Cohen was removed in the final report from the FCIC.)

“In 1991, Goldman Sachs and other large securities firms sought legislation that would give them greater access to the Fed’s emergency lending facility under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Goldman and the other firms were concerned about ‘the absence of a safety net beneath Wall Street firms’ in light of (i) the reluctance of some commercial banks to provide credit to securities broker-dealers during the 1987 stock market crash, and (ii) the failure of Drexel in 1990. At the suggestion of H. Rodgin Cohen, a banking lawyer with Sullivan & Cromwell in New York City, the securities firms urged Congress to include an amendment to Section 13(3) in FDICIA.

“The enacted 1991 amendment to Section 13(3) authorized the Fed to make emergency loans to nonbanking firms as long as those loans are ‘secured to the satisfaction of the [Fed],’ and the amendment also gave the Fed broad discretion to accept almost any type of collateral from the borrowing firms.”

The Federal Reserve was created in 1913 and throughout its history until the 2007-2008 financial crisis its role was seen as lender of last resort to the commercial banks of the United States, not high-risk securities firms on Wall Street. According to a history provided by David Fettig, a Senior Advisor to the Minneapolis Fed, Section 13(3) “was used sparingly, and just 123 loans were made” from 1932 to 1936 during the prior great crash on Wall Street. The loans totaled $1.5 million or approximately $27.3 million in today’s dollars. The 1936 loans were the last time 13(3) was invoked until 2007.

The GAO report tallied up just over $16 trillion in cumulative loans that the Federal Reserve had made to Wall Street and global banks from late 2007 until the middle of 2010 under a labyrinth of expansive programs. But the GAO failed to report numerous Fed operations like the ST OMO and its dollar swap lines to foreign central banks. When all of the programs were added up by academic researchers, the Levy Economics Institute reported the cumulative tally of $29 trillion.

Despite this irresponsible and unaccountable history by the Fed, Congress has failed to hold one hearing on what the Fed is doing today.

Federal Reserve’s 24 Primary Dealers as of October 7, 2019 (Source — Federal Reserve Bank of New York)

Related Articles:

New Documents Show How Power Moved to Wall Street, Via the New York Fed

Two Key Execs at New York Fed Head for the Exits – Two Business Days After Sharp Cut in GDP Estimate

The Contagion Deutsche Bank Is Spreading Is All About Derivatives

Who is Morgan Stanley and Why Its $31 Trillion in Derivatives Should Concern You

Financial System of U.S. Rests on Health of Just Five Mega Banks