By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 1, 2018 ~

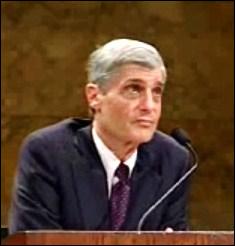

Robert Rubin, Former Treasury Secretary and Chair of the Citigroup Executive Committee for Almost a Decade

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary, Robert Rubin, has decided he wants to rewrite his resume, removing the ugly warts from his days at Citigroup. That mega bank started as a financial supermarket that Rubin helped to make possible behind the scenes in the Bill Clinton administration, followed by a giant crash and the largest bank bailout in U.S. history from 2007 to 2010. Rubin strolled out the door of Citigroup in early 2009 $120 million richer than when he originally rolled his shopping cart into the well-stocked aisles of hubris at Citigroup almost a decade earlier.

The New York Times has apparently decided to help Rubin exorcise Citigroup from his past. In an OpEd in the New York Times New York edition today, neither he nor the New York Times in its bio mentions so much as a syllable about Rubin’s infamous tenure at Citigroup. The uninformed reader would assume that Rubin is a veteran of Goldman Sachs and a former U.S. Treasury Secretary and there’s nothing more to see here.

But there’s plenty that the public needs to remember about Rubin and Citigroup –and that history makes the thrust of Rubin’s OpEd akin to a Saturday Night Live satire.

Rubin’s curious point in the OpEd is that it wasn’t “courses in economics or finance” from his days at Harvard that prepared him “for working at Goldman Sachs and in the government” (notice the almost decade-long stretch at Citigroup is completely missing) but instead “the key was Professor Demos’s philosophy course and the conversations about existentialism in coffee shops around campus.”

The shareholders of Citigroup who are still nursing stock losses of 85 percent from the bank’s pre-crash days aren’t going to be too comforted by reading about Rubin’s musings about existentialism in coffee shops around Harvard when he should have been cramming for finance courses that might have led to his questioning the more than $1 trillion bucks that Citigroup held off its balance sheet in the leadup to its crash.

Rubin would like us to believe that one of the scariest moments in his career came at Goldman Sachs where he showed calm, steely resolve and “weathered the storm.” Rubin writes:

“There was a point in the early 1980s when the Goldman Sachs arbitrage department, which I led, lost more money in one month than it had made in almost any one year, driven by severe declines in the equity markets. Given the vicissitudes of markets, there was no way to tell whether we’d reached the nadir and recovery was around the corner — or whether we were about to go over a cliff. Despite the immense pressure, and the emotional state of the markets, I drew on an existential perspective, and my colleagues and I made careful, probabilistic decisions to adjust our portfolio, and we weathered the storm.”

What the public learned in Senate hearings after the 2008 crash and Justice Department charges is that Goldman Sachs wasn’t so much about existential thinking as it was about selling off its toxic holdings to customers as good investments and then shorting the hell out of them.

But, to be fair, Rubin wasn’t at Goldman Sachs in the leadup to the epic 2008 Wall Street crash which was the most financially devastating event in the U.S. since the Great Depression. Rubin went directly from U.S. Treasury Secretary to become Chair of the Executive Committee at Citigroup in 1999. He remained in that position until he stepped down in January 2009 as the bank was imploding. In the leadup to the financial crisis, Rubin was briefly named Chairman of the Board of Directors of Citigroup in 2007.

Rubin’s decision to share his story about financial losses at Goldman Sachs where he “weathered the storm” using his magical existential thinking stands in contrast to Citigroup’s condition with Rubin as the long-tenured Chair of the Executive Committee. On November 28, 2008 we wrote the following about Citigroup’s condition:

“Citigroup’s five-day death spiral last week was surreal. I know 20-something newlyweds who have better financial backup plans than this global banking giant. On Monday came the Town Hall meeting with employees to announce the sacking of 52,000 workers. (Aren’t Town Hall meetings supposed to instill confidence?) On Tuesday came the announcement of Citigroup losing 53 per cent of an internal hedge fund’s money in a month and bringing $17 billion of assets that had been hiding out in the Cayman Islands back onto its balance sheet. Wednesday brought the cheery news that a law firm was alleging that Citigroup peddled something called the MAT Five Fund as ‘safe’ and ‘secure’ only to watch it lose 80 per cent of its value. On Thursday, Saudi Prince Walid bin Talal, from that visionary country that won’t let women drive cars, stepped forward to reassure us that Citigroup is ‘undervalued’ and he was buying more shares. Not having any Princes of our own, we tend to associate them with fairytales. The next day the stock dropped another 20 percent with 1.02 billion shares changing hands. It closed at $3.77.

“Altogether, the stock lost 60 per cent last week and 87 percent this year. The company’s market value has now fallen from more than $250 billion in 2006 to $20.5 billion on Friday, November 21, 2008. That’s $4.5 billion less than Citigroup owes taxpayers from the U.S. Treasury’s bailout program.”

As a result of an amendment tacked on to the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation by Senator Bernie Sanders, a General Accountability Office report eventually revealed in 2011 that the Federal Reserve had pumped $16 trillion in almost zero interest secret loans to Wall Street to save it from its own hubris. Citigroup received $2.5 trillion of those loans from late 2007 to the middle of 2010. In addition, Citigroup received $45 billion in capital from the U.S. Treasury; the Federal government guaranteed over $300 billion of Citigroup’s assets; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits. This was the largest bank bailout in global banking history.

There’s another critical reason that Rubin wants to cleanse his resume from the tarnish of Citigroup. In March of 2016, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) released thousands of documents that indicated that it had made multiple referrals to the Department of Justice to pursue potential criminal charges against individuals. In September of 2016, Senator Elizabeth Warren sent a 20-page letter to the Inspector General of the Department of Justice, Michael E. Horowitz, asking for an investigation into why the DOJ had failed to indict any of the Wall Street executives that had been referred to it by the FCIC. In a separate letter, Warren asked then FBI Director James Comey for his related files. In her letter to the Inspector General of the DOJ, Warren wrote:

“A review of these documents conducted by my staff has identified 11 separate FCIC referrals of individuals or corporations to DOJ in cases where the FCIC found ‘serious indications of violations[s]’ of federal securities or other laws. Nine individuals were implicated in these referrals (two were implicated twice). The DOJ has not filed any criminal prosecutions against any of the nine individuals. Not one of the nine has gone to prison or been convicted of a criminal offense. Not a single one has even been indicted or brought to trial. Only one individual was fined, in the amount of $100,000, and that was to settle a civil case brought by the SEC.”

The two individuals Warren refers to who were “implicated twice” in the FCIC’s criminal referrals are Robert Rubin and Chuck Prince, Citigroup CEO during its implosion. A third Citigroup executive was also on the list, Gary Crittenden, the CFO at Citigroup at the time of its crash. Crittenden is the person who was fined $100,000 by the SEC for grossly misstating to the public the amount of Citigroup’s subprime debt exposure.

The public heard nothing further about Senator Warren’s inquiries over the next year. Wall Street On Parade decided to file a Freedom of Information Act request on the matter with the Justice Department in October 2017. (You can read the full response we received and our reporting on the matter here.) The DOJ effectively stiffed us in receiving any meaningful response.

Existential thinking did actually come in handy when Rubin was hauled to testify before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission on March 11, 2010. (Read the full transcript here.) Rubin responded “I don’t remember” 41 times during the interview. Rubin didn’t rely solely on existentialism, however. Some invisible hand had comfortably arranged for Rubin to forego taking an oath prior to his testimony. Perhaps it was his team of six lawyers from two of the most powerful corporate law firms in America: Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and Williams & Connolly. One of Rubin’s lawyers from Paul, Weiss was Brad Karp, the lawyer who has gotten Citigroup out of serial fraud charges in the past.

America is still living through the crippling ravages left in the wake of the 2008 financial crash. The country has the greatest wealth inequality since the late 1920s and trust in American institutions, including media and Congress, is hovering near all-time lows. Surely the New York Times can find something better to do with its newsprint than help Robert Rubin write a preposterous resume of his days on Wall Street.