By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 16, 2016

On December 6, the Gallup organization together with the U.S. Council on Competitiveness published a jolting study demonstrating that the pervasive sense among Americans that the U.S. is in economic decline isn’t imagined. It’s real and it’s dangerous.

The study was conducted by Gallup’s Senior Economist, Jonathan Rothwell, with other Gallup experts and external scientists serving as reviewers to “ensure statistical and theoretical accuracy and objectivity,” according to Gallup Chairman and CEO Jim Clifton.

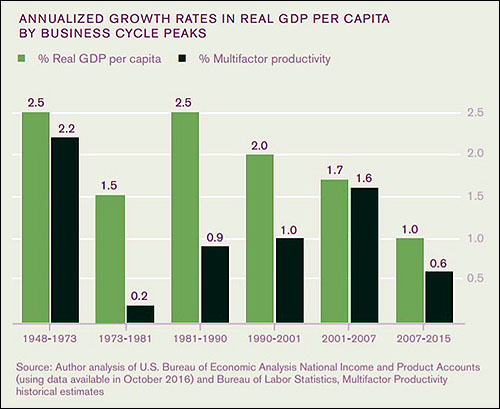

The problem, in a nutshell, is this: real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita ran at a rate of 2.4 percent per year from 1929 to 1979. But since 2007, real GDP per capita has been a negligible 1 percent. Since the depths of the Wall Street crash in 2009, it has been a paltry 1.4 percent. (GDP per capita is the value of all goods and services produced in a country, divided by the number of people living in the country at the time.)

Jim Clifton adds this perspective in a letter attached to the report to drive home the point that America “is dangerously running on empty”:

“Think of our country as a company, America Inc., which has more than 100 million full-time employees, with about $18 trillion in sales and $20 trillion of debt. The most serious problem facing it is no growth.”

The study places the bulk of the blame for shrinking productivity on three sectors: healthcare, education and housing. Soaring costs and inefficiencies in these sectors are barriers to innovation and entrepreneurship, which in turn is holding back growth in GDP, according to the study. This analysis is offered:

“…the deterioration clearly links to specific regulations and inefficiencies created by government and industry practices that are entirely reversible. There is no inherent reason, for example, that the U.S. healthcare system needs to devote hundreds of billions of dollars to administrative expenses related to billing and claims processing, or that higher education now employs more professionals and executives than it does teachers, or that municipalities with the highest demand for housing refuse to allow multi-family housing to be built on under-utilized land. Eliminating these market barriers and the related waste and inefficiency would return the United States to rapid growth even without a spike in invention.”

Rothwell concedes in the study that there are widely divergent opinions among economists as to what is causing the low growth rate, writing:

“Another theory for why productivity growth has slowed is that demand for investment has fallen. Reviving a theory from the 1930s, Larry Summers has argued that the fundamental problem is a lack of investment opportunities. Summers provides few details as to why he thinks investment demand has fallen, but he argues that large-scale government-funded investment is a potential cure. Yet, weak demand for investment may be an effect of a still more fundamental change. Lower real wage growth, for example, would depress opportunities for businesses to form or expand, depressing investment. So, if Summers is right, the question remains: Why has investment demand become so weak? If consumers could afford to buy new goods and services, then businesses would have a strong incentive to invest in providing them.

“Macroeconomist Kenneth Rogoff has taken almost the opposite view of Summers, arguing that excessive debt is dragging down growth, resulting from the collapse of the housing bubble. Whereas Summers recommends increased government borrowing to fund investments, Rogoff argues this will exacerbate long-term problems.”

In our opinion, the one sector that should be singled out in any study of declining GDP growth in the U.S. is Wall Street. It has sacked the current and future prospects for the country in so many ways that it is beyond comprehension that any economic study on subpar growth wouldn’t first look in its direction.

In a study in November 2009, two researchers did take a cold, hard look. David Weild and Edward Kim authored a study for the accounting firm, Grant Thornton LLP titled “A Wakeup Call for America.” The study found that since 1991, the number of U.S. exchange-listed companies is down more than 22 percent, and when adjusted for real GDP growth (inflation-adjusted), that percentage balloons to a stunning 53 percent.

The authors trace the decline in IPOs to the disappearance of the Four Horsemen, four boutique investment banks which played an outsized role in bringing innovative companies to market: Alex. Brown & Sons, Robertson Stephens, Montgomery Securities, and Hambrecht & Quist. These super job creators were gobbled up by the same Wall Street behemoth banks that have eviscerated so much else that was good in America – like the separation of insured banks from speculating dark pools and derivative desks.

As we reported in 2012:

“Alex Brown’s roots dated back to 1808. It was involved in the IPO of Microsoft and Oracle Systems. It was acquired by Bankers Trust in 1997 and two years later merged into the German behemoth Deutsche Bank.

“Robertson Stephens was a much younger firm, starting out in 1978. The firm was involved in the IPOs of Sun Microsystems, Excite and Chiron. Before being sold to BankAmerica for $540 million in 1997, the company was lead or co-manager on 10 of the top 25 best IPO performers in 1997. (The firm was resold several times after that, each time to a large commercial bank and eventually liquidated.)

“Montgomery Securities, heavily involved in high-tech issues, was sold to Nationsbank for $1.2 billion in 1997. Nationsbank would acquire BankAmerica the following year, but keep the name BankAmerica as the legal entity. In 2008, during the financial crisis, BankAmerica purchased the large retail brokerage firm, Merrill Lynch, which was teetering near insolvency.

“Boutique investment bank, Hambrecht & Quist, was the final of the Four Horsemen. The firm was founded by Bill Hambrecht and George Quist in 1968. The firm was the underwriter of the following well known firms: Apple Computer, Genentech, Adobe Systems, Netscape, and Amazon.com. In September 1999, Chase Manhattan Bank acquired the firm for $1.35 billion. The firm is now part of the largest U.S. bank, JPMorgan Chase.”

Each of the behemoth banks mentioned above (Deutsche Bank, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase) that gobbled up the super productive investment boutiques, have been repeatedly charged with frauds against the public and added enormously to the U.S. national debt by forcing the government to enact fiscal stimulus measures to compensate for the 2008 to 2010 economic collapse — which these and other Wall Street banks triggered through their corruption.

Another major problem is that when Wall Street investment banks were partnerships, they had to put the partners’ own money at risk in the deals they engaged in or brought to market. Today, every major Wall Street firm is publicly traded and owns a commercial bank holding the insured deposits of Moms and Pops across the country, thanks to the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999. Instead of worrying about losing their own principal if they bring “crap” or “dogs” to market as IPOs, they have been caught actually bragging about doing just that. They are now, in many cases, simply selling companies with a sexy story rather than companies with solid prospects for innovation or job creation potential. Equally problematic, much of what these banks do today is to facilitate high frequency trading in a quest for outsized profits. This trading provides no meaningful benefit to society or the overall economy. It is pure casino capitalism.

More recently, economist Michael Hudson delivered a powerful critique on how Wall Street is crippling America in his 2015 book “Killing the Host.” Hudson explains how these financial parasites have tricked our society into accepting them as a normal, productive part of our economy. This depraved financial model which imploded in 2008 in the worst crash since the Great Depression should have brought an end to itself as a result. Instead, says Hudson, “Any given development crisis is said to be a natural product of market forces, so that there is no need to regulate and tax the rentiers.”

Chapter 8 of “Killing the Host” begins with this quotation from John Maynard Keynes: “When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.” Hudson explains further:

“Instead of warning against turning the stock market into a predatory financial system that is de-industrializing the economy, [business schools] have jumped on the bandwagon of debt leveraging and stock buybacks. Financial wealth is the aim, not industrial wealth creation or overall prosperity. The result is that while raiders and activist shareholders have debt-leveraged companies from the outside, their internal management has followed the post-modern business school philosophy viewing ‘wealth creation’ narrowly in terms of a company’s share price. The result is financial engineering that links the remuneration of managers to how much they can increase the stock price, and by rewarding them with stock options. This gives managers an incentive to buy up company shares and even to borrow to finance such buybacks instead of to invest in expanding production and markets.”

We suggest the Gallup folks and the U.S. Council on Competitiveness seriously delve into the issues raised by David Weild, Edward Kim and Michael Hudson. No meaningful conversation about what is holding back America can take place without a comprehensive understanding of Wall Street’s broken, corrupt business model.