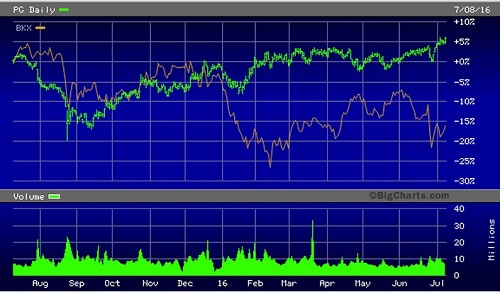

Procter and Gamble, a Consumer Staples Stock (Green Line), Versus KBW Bank Index, Stock Symbol: BKX (Orange Line), Over the Past 12 Months

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: July 11, 2016

If it’s any comfort, and it likely won’t be, markets are now even more bizarre than the situation of the two presumptive candidates for the President of the United States: one is escaping indictment for treating above Top Secret material with the seriousness of a drunken frat boy at an all-night party while the other is hurling adolescent insults on his Twitter page. This in a country where the Commander in Chief will oversee more than 7,000 nuclear warheads.

On Friday, the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index traded intraday at a new high of 2131.71, beating its prior closing high of 2130.82. It closed a tad lower at 2129.9 but still up 1.53 percent on the day. A rally in the stock market would normally drain money from U.S. Treasury notes, since a stock rally means confidence in a growing economy while a rally in Treasury securities would normally suggest a flight to safety over fears of a weakening economy. But that didn’t happen Friday.

As the S&P 500 flirted with an all-time high, the 10-Year U.S. Treasury note also rallied in price, dropping its yield to a record low of 1.366 percent. To fully contemplate what a record low yield on the 10-year Treasury is suggesting, one needs to reflect on the fact that during the Civil War when the country was torn in half, the 10-year T-Note yielded above 5 percent; during the Great Depression, with over 20 percent unemployment and raging deflation, the 10-year T-Note yielded over 2 percent.

According to corporate media headlines, we are not in a Great Depression so why are we plumbing the depths of historic low yields? We won’t know what this era will be called until the history books are written many years from now, but we have a strong suspicion about what those history books will say. (We’ll get to that in a moment.)

Much ado was made on Friday by corporate media headline writers about the “blockbuster” or “upbeat” jobs report released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics showing that 287,000 new jobs were created in June. But averaged together with April and the frighteningly-low job growth in May (May was revised down to a shocking 11,000 jobs) and you’re looking at a tepid average of 147,000 jobs growth per month in the second quarter.

Adding to the speciousness of this big stock rally on Friday, with the Dow up 250.8 points, is what is happening in the financial sector, which we have been reporting for some time now. (See here, here and here.) As the overall market flirts with new highs, capital is bleeding from the mega banks – which are normally viewed as bellwethers for the health of the overall market and economy.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal tallied up the losses and ran this sobering headline: “The Big-Bank Bloodbath: Losses Near Half a Trillion Dollars.” According to the author of the article, David Reilly: “Since the start of 2016, 20 of the world’s bigger banks have lost a quarter of their combined market value. Added up, it equals about $465 billion, according to FactSet data.”

Hasn’t the Federal Reserve been reassuring the public that the capital is just fine at the big Wall Street banks? If things are not fine, why is the Federal Reserve allowing banks to spend their dough buying back their own shares and paying out dividends? The continuing sell off in banks may represent a sell off in confidence in central banks’ ability to understand global banking behemoths. Which brings us to the next Alice in Wonderland aspect of the market.

According to a research note from Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, there is now $13 trillion in global bonds yielding less than zero, i.e., a negative yield. What does it say about investors’ view of risk in the stock market when they are willing to accept less than zero on government bonds to avoid being in stocks?

On Thursday and Friday of this week, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Wells Fargo will report their second quarter earnings. Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America will follow next week. According to Zacks Investment Research, the consensus of analysts expect bank earnings to be down significantly from the second quarter of 2015.

The big six Wall Street banks and/or their bank holding companies have a total of more than $200 trillion in notional (face amount) of derivatives. The investing community has no clarity on exactly what institutions are on the hook for derivative losses as counterparties to these trades. In times of market turmoil, as with the uncertainty brought on by the Brexit vote in the U.K., sophisticated investors tend to head to the safety of government bonds and avoid the dark corners of the market.

The United States has now been growing at two percent or less since the Wall Street crash of 2008. That’s eight long years. The Fed promised on December 16, 2015 with its first rate hike since the crisis to begin normalizing rates and exiting its zero-interest-rate-policy (ZIRP). Here’s the Alice in Wonderland aspect of the Fed’s promise of normalization: on December 16, 2015, at the time of the Fed rate hike, the yield on the 10-year T-Note stood at 2.29 percent. Last Friday, the 10-year T-Note closed with a yield of 1.366 percent. Senior citizens hoping to invest for safety and use the income to buy groceries and pay bills, are receiving 40 percent less when they buy the 10-year T-Note today than seven months ago. There’s simply nothing normal about that.

A political system ruled by two party machines financed by the one percent; a financial system ruled by six Wall Street banks who are major political financiers and government lobbyists; and a corporate media concentrated in six large corporations, is not likely to confess to the public that the United States is on a glide path of more economic pain because of the concentrated wealth of the one percent.

But that’s exactly what the disease is. Everything else you are witnessing represents the symptoms of the disease.

The late Lester Thurow, the prominent MIT economist, explained the problem in crisp layman’s prose in a forward he wrote in Ravi Batra’s book, “The Great Depression of 1990.” Batra obviously got his date wrong but Thurow was spot on with his analysis on concentrated wealth. Thurow wrote:

“Depression is seen as a product of systematic tendencies for the distribution of wealth to become concentrated among a few. When this happens, demand eventually sags relative to supply and long cyclical downturns commence. Unlike some cyclical analysts, Batra believes that such cycles are not inevitable and can be controlled with social policies essentially designed to stop undue concentration of wealth from developing.

“Essentially, the economic problem is like that of the wolf and the caribou. If the wolves eat all the caribou, the wolves also vanish. Conversely, if the wolves vanish, the caribou for a time multiply but eventually their numbers become too great and they die for lack of food. Producers need consumers, and if producers deprive workers of their fair share of production income they essentially deprive themselves of the affluent consumers they need to make their facilities profitable. One could think of Batra’s argument as a kind of economic ecology where there is a ‘right’ environmental balance.”

Presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders, former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, and Batra have each written about the fact that the U.S. now has the greatest wealth and income inequality since the period just prior to the 1929 crash and the Great Depression. Senator Sanders has explained further:

“There is something profoundly wrong when the top one-tenth of one percent owns almost as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent. There is something profoundly wrong when 58 percent of all new income since the Wall Street crash has gone to the top one percent.”

The Alice in Wonderland quality of markets and yields and presidential candidates all stems from a simple understanding of the wolves and the caribou.