By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 11, 2016

At 8:00 a.m. this morning, futures on the Dow Jones Industrial Average were flashing a 274 point plunge at the open of the stock market at 9:30 a.m. ET, following a selloff of 99.64 points by the close of trading yesterday.

There’s plenty of things rattling this market, not the least of which is the continued weakness in the share prices of the mega Wall Street and European banks. Analysts have started asking on business news outlets if there is something going on that the public can’t see.

Adding to the market angst was the jumble of questions Fed Chair Janet Yellen received during her semi-annual testimony before the House Financial Services Committee yesterday. One particular line of questioning from multiple members of the Committee was on whether the Federal Reserve has the legal authority to use negative interest rates as part of its monetary policy tools. Central banks in Europe and the Bank of Japan have deployed negative rates and financial markets have a built-in assumption that the Fed could do likewise. Yellen threw a bucket of cold water on that assumption with two revealing remarks.

First, Yellen said that the Fed had looked at the possibility of using negative rates in 2010, explaining:

“We got only to the point of thinking it wasn’t a preferred tool. We were concerned about the impact it would have on money markets. We were worried it wouldn’t work in our institutional environment.”

If you’re a hedge fund and you’ve staked a billion dollar bet on the potential for the Fed using negative rates in the U.S., this is not the answer you wanted to hear.

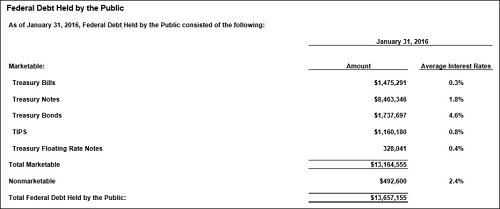

The words “money market” likely sent both a shiver and an epiphany throughout Wall Street. Why would money markets pose an obstacle to the Fed in embarking on negative interest rates? Because there are a multitude of money market funds in the U.S. that are predominantly holdings of U.S. Treasury instruments. Vanguard, T. Rowe Price, Fidelity, Schwab, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo and many more mega institutions have money markets funds that are designated as “U.S. Treasury” Money Market Funds. The concept behind an interest-bearing money market fund, particularly one whose portfolio is filled with U.S. Government backed Treasury securities, is that it will trade at $1 and will not “break the buck,” thus providing a ready source of liquidity when needed. (Some non-Treasury money markets have experienced losses in the past and broken the buck, but it’s a rare occurrence.)

As of this morning, the 3-month, 6-month and 1-year U.S. Treasury bills are yielding 0.28 percent; 0.37 percent and 0.45 percent respectively. The way T-bills work is that you buy them at a discount and the Treasury pays you par at maturity (full face amount at maturity). Here’s how the U.S. Treasury explains how you get your interest on a T-bill:

“For example, a $10,000 bill may be sold at issue for $9,900. In this case, the investor receives $10,000 when the bill matures; therefore, the interest is $100. The interest is determined by the discount rate, which is competitively determined when the bill is auctioned. It is possible for a bill auction to result in a price equal to par, which means that Treasury will issue and redeem the securities at par value.”

Okay. Fair enough. Right now, according to the U.S. Treasury Department, the worst thing that can happen to you is that you could pay par (the full $10,000) and receive back par (the full $10,000). But if the Fed adopted negative interest rates, you could actually get back less principal than you invested.

One can just imagine what the conservative wing would do to the Fed Chair in these semi-annual hearings if a formal Fed policy of negative interest-rates started confiscating T-bill principal from the accounts of widows and orphans and struggling seniors.

Speaking of seniors, lots and lots of them hold their Treasury Bills, Notes and Bonds at TreasuryDirect, a program where you buy directly from the Treasury and it holds your securities (book entry) for you and will credit your interest to a checking account of your choice. Imagine what would happen if seniors who have been using this program for decades without misadventure suddenly learned that it was not paying them interest and shrinking their principal and it was a result of a formal policy by the Fed.

The Fed not being able to deploy negative rates in the U.S. is a scary thought to financial markets on a number of fronts. First and foremost, the Fed is already close to the zero bound range and thus has little in its arsenal in terms of being able to slash interest rates if the U.S. enters recession. Its existing $4.5 trillion balance sheet, resulting from three prior rounds of quantitative easing (QE) to shore up the economy from the effects of the 2008 crash, is another headwind to getting consensus at the FOMC to launch more QE in a serious downturn.

That the Fed is not seriously considering using negative rates gathered further steam when Congressman Patrick McHenry asked Yellen if the Fed actually had the legal authority to do so. Yellen said that as far as she was aware the Fed had not obtained a formal legal opinion on the matter. Surely that step would have been completed if the Fed was seriously considering this avenue.

More than half way into the hearing, Congressman Ed Royce asked if the inclusion of a hypothetical scenario of the 3-month Treasury bill going negative beginning in the second quarter of 2016, which was included in the Fed’s stress tests scenarios for the systemically important banks, was indicative that the Fed might be considering using negative rates as part of its monetary tool kit. Yellen made two key remarks in this regard. First, she correctly explained that T-bills could go negative in the U.S. without the Fed taking any action. Second, she suggested that this could be the outcome of a flight to safety into U.S. government securities. (See video clip below.)

While Yellen was not specific, that flight into U.S. government securities could actually be either a flight for yield from yield-starved foreigners and/or a flight to safety from growing worries about another global banking crisis.