By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 21, 2016

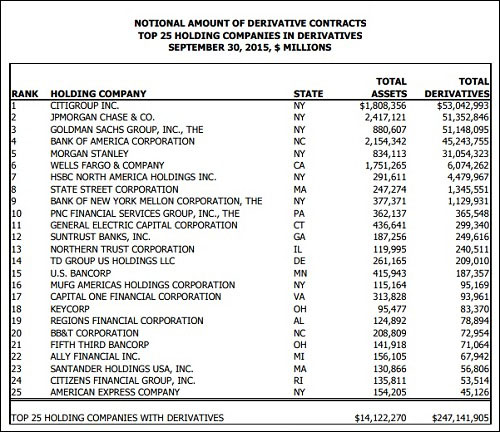

According to a report from one of the regulators of national banks, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, as of September 30, 2015, insured U.S. commercial banks and savings associations had exposure to $192.2 trillion notional (face amount) of derivatives. (Yes, that’s trillion with a “t”.) The report goes on to terrify with the revelation that only four banks hold 90.8 percent of all derivatives: Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America.

But that’s far from an accurate picture. Buried deep in the report is Table 2, which broadens the landscape beyond just the commercial banking units of the mega Wall Street firms to what is lurking in the holding companies. In Table 2 we learn that Morgan Stanley ranks right up there with the other big boys on Wall Street, holding $31 trillion notional in derivatives. (See chart below.)

Adding in Morgan Stanley’s derivatives, the total rises to $247 trillion in notional derivatives with just these five banks holding 93 percent of the total. Equally noteworthy, the table shows that within Morgan Stanley’s $31 trillion in derivatives there are $1.6 trillion in notional credit derivatives – those pesky instruments that took down the big insurer AIG in 2008 and almost took down Morgan Stanley.

Since July of last year, Morgan Stanley’s share price has been on a slow bleed, closing yesterday at $25.24 – a loss of 38 percent from its July high of $41.04. That’s not the kind of trading action that one wants to see from financial institutions holding hundreds of billions of dollars in the life savings of Americans.

Who and what exactly is Morgan Stanley and why should its derivatives concern us? Morgan Stanley was created in 1935 after the Glass-Steagall Act barred JPMorgan from holding insured deposits while simultaneously operating an investment bank to engage in underwriting and speculating in stocks. The massive losses experienced by banks after the 1929 crash was blamed on reckless speculations in the stock market and a leading cause of the Great Depression. Prior to the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933, there was no FDIC insurance on bank deposits, thus millions of people lost everything that had been in the failed banks as a result of the crash. JPMorgan chose to remain a commercial bank accepting newly insured deposits while other partners left the firm to form the investment bank, Morgan Stanley.

In 1997, investment bank Morgan Stanley, which was primarily engaged in acquisition and merger activity and other advisory services to large corporations and institutions, merged with Dean Witter, Discover & Co., a retail brokerage firm with 9,000 brokers managing mom and pop investment accounts in 361 offices across America. In 2009, its retail brokerage and mom and pop accounts became exponentially larger when Morgan Stanley took over the retail broker, Smith Barney. (Smith Barney had consumed another brokerage firm, Shearson Lehman Brothers Inc., in 1993.)

Last July Morgan Stanley reported that it now has 15,771 retail brokers. In its third quarter report for 2015 it reported that it had $404 billion in assets under management – that means how much it is managing of other people’s money, much of which are accounts for moms and pops, retirees and pension and retirement accounts.

Could Morgan Stanley’s derivatives pose a problem for it? Why does the composite wisdom of the stock market view its stock value at 38 percent less than it was in July? Two words may help answer that question: Howie Hubler.

You won’t see Howie Hubler paying a role in the movie The Big Short but you will find a great deal about him in the book on which the movie is based, Michael Lewis’s The Big Short. Lewis says Hubler was the star bond trader at Morgan Stanley, making $25 million in one year prior to the subprime mortgage market crash. Hubler was one of those who bet early on that lower rated subprime bonds would fail, using credit default swaps (derivatives) to make his bets. But because he had to pay out premiums on these bets until the collapse came, he placed $16 billion in other bets on higher rated portions of the subprime market, according to Lewis in his book. When those bets failed, Morgan Stanley lost at least $9 billion.

To survive the 2007-2009 Wall Street crash and Hubler’s losses, Morgan Stanley received an injection of $9 billion from the Japanese bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group; a $10 billion injection from the U.S. government and over $2 trillion in secret, cumulative, below-market-rate loans from the Federal Reserve. According to data obtained by Bloomberg News following a multi-year court battle to obtain the information from the Federal Reserve, Morgan Stanley’s one-day secret outstanding loans from the Fed peaked at $107.3 billion on September 29, 2008.

The public would have never known about these secret loans shoring up Wall Street’s reckless conduct and hubris and obscene bonuses except for the court battle of Bloomberg News and legislation secured by Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont requiring a Fed accounting.

Wall Street On Parade decided to see if Wall Street’s regulators have become more obliging and transparent with the public’s right to know following the greatest Wall Street collapse since the Great Depression. We emailed the SEC and inquired as to why it was allowing a bank holding millions of brokerage accounts for moms and pops across America to simultaneously be housing $31 trillion in derivatives. We received an email back from Judith Burns in the SEC’s Public Affairs office with this: “Decline comment, thanks.”

If you are counting on the SEC to have your back in the next crisis, our opinion is — don’t.

Related Article:

Warren: Citigroup, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch Received $6 Trillion Backdoor Bailout from Fed