By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 4, 2015

The monetary policy arm of the U.S. central bank, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), is getting hammered this week. On Monday, two researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco chastised the FOMC for effectively wearing rose-colored glasses since 2007 and getting the rate of economic growth mostly dead wrong. (More on that later in this article.)

Yesterday, in a speech before the Minnesota Bankers Association, Narayana Kocherlakota, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis said that if one applied a corporate performance measurement to the FOMC’s dual job assignment from Congress of promoting price stability and maximum employment, then the FOMC has “underperformed in the past three years” on both measures.

The reason the FOMC has underperformed according to Kocherlakota is that it did not provide adequate stimulus. The Fed President told the audience:

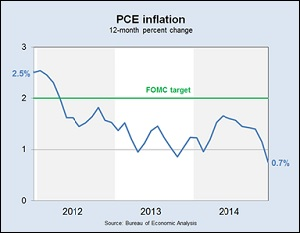

Narayana Kocherlakota, President of the Minneapolis Fed, Used This Graph Yesterday in a Speech to Show How the FOMC Could Have Provided More Stimulus to Increase Employment in Order to Reach Its Goal of 2 Percent Inflation. Instead, the Rate of Inflation Has Been Steadily Declining.

“What concrete actions could the FOMC have taken to provide additional stimulus? I think one concrete action would have been not to reduce stimulus. In mid-2013, the FOMC began communicating about the eventual elimination of its asset purchase program that took place from December 2013 and October 2014. These communications, and the follow-up actions, served as a tightening of monetary policy. Accordingly, they were associated with sharp increases in market interest rates and sharp reductions in the rate of home mortgage refinancing.”

To back up his thesis, Kocherlakota correctly points to how the FOMC has consistently failed to meet its inflation target of 2 percent for the past three years. If employment growth had indeed been adequate, there would have been upward pressure on inflation. Kocherlakota told the crowd:

“Recall that monetary stimulus pushes both employment and prices in the same direction. By providing somewhat more stimulus, the FOMC could have stimulated at least somewhat more employment growth, without creating undue inflation. I am sure that this faster employment growth would have been welcomed by the American public. So, even though employment grew, it seems that there was an improvement opportunity: The FOMC should have facilitated even faster employment growth.”

Kocherlakota delivered one final message to the FOMC: don’t raise rates in 2015. “Raising the target range for the fed funds rate in 2015,” said Kocherlakota, “would only further retard the pace of the slow recovery in inflation. It would also increase the risk of a loss of credibility, in the sense that the public could increasingly perceive the FOMC as aiming at a lower inflation target…Deciding not to reduce stimulus in 2015 would also be consistent with a goal-oriented approach to the employment mandate. Increases in stimulus would push upward on employment. Such an increase in employment is entirely consistent with the pursuit of maximum employment that Congress has mandated for the FOMC.”

The day before the Minneapolis Fed President dropped his underperformance report on the FOMC, Kevin Lansing and Benjamin Pyle, two researchers in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, produced a study showing that since 2007 the FOMC has repeatedly been overly optimistic in forecasting the rate of economic growth in the U.S.

FOMC projections for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are reported in its Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). According to Lansing and Pyle, the FOMC’s SEP “(1) did not anticipate the Great Recession that started in December 2007, (2) underestimated the severity of the downturn once it began, and (3) consistently overpredicted the speed of the recovery that started in June 2009. The SEP growth forecasts have typically started high, but then are revised down over time as the incoming data continue to disappoint.”

The researchers produced a chart showing that the SEP forecast for 2008 never turned negative while the “actual growth rate for 2008 turned out to be –2.8% —the largest annual decline since 1946.”

Equally troubling, the FOMC’s SEP forecasts for 2011 through 2013 started at around 4 percent or higher – a rate of growth not seen in the U.S. since the tech-bubble years of 1996 through 1999. According to the researchers, “The overoptimistic SEP growth forecasts for 2011 through 2013 were eventually cut in half, each ending around 2%. The actual growth rates for those years were 1.7%, 1.6%, and 3.1%.”

Lansing and Pyle believe that a possible explanation for the FOMC’s overly rosy predictions is that the Committee is failing to grasp the inability of monetary policy to deal with a balance-sheet recession. The researchers write:

“Recessions triggered by financial crises are typically preceded by sustained episodes of bubbly asset prices and debt-financed spending booms. When the bubble bursts, the resulting debt overhang forces borrowers to repair their balance sheets via reduced spending or default. Borrowers have too much debt, so monetary policy actions designed to encourage more borrowing by lowering interest rates are less effective. Balance-sheet recessions are typically followed by sluggish recoveries and permanent output losses, that is, real GDP never returns to its pre-crisis path.”

Unfortunately for Americans, the Fed’s FOMC continues to talk about raising interest rates on the basis of “solid” economic growth and “strong job gains” — despite its poor performance in anticipating what’s coming down the pike.