By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 4, 2014

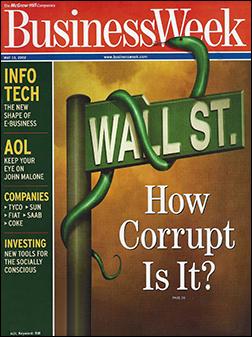

Yesterday, Wall Street on Parade reported on how the corrupt tentacles of Wall Street have engulfed the mindset of our newly minted law school graduates.

Getting one’s resume noticed from those of a stack of competitors previously meant using a good grade ivory linen stock instead of cheap white copy paper. Today, the word is apparently out that getting one’s resume noticed at a major Wall Street bank requires advertising one’s special knack, inside track, or secret sauce for ripping off society for the profit advantage of the big dogs on Wall Street.

On November 20, Senator Carl Levin and the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations released a 396-page report and 8-inch stack of exhibits exposing more shocking Wall Street secrets that have been heretofore protected from daylight by timid or captured regulators. Among the exhibits was a resume submitted to JPMorgan Chase by a young, recent graduate of George Washington University Law School – a man that society might rightfully expect to conduct himself in an honorable and professional manner in the business world.

This young man, instead, attempted to set himself apart from the pack of recent law grads applying for jobs at JPMorgan by advertising at the very top of his resume that during his job in power procurement at Southern California Edison, he had “identified a flaw in the market mechanism Bid Cost Recovery that is causing the CAISO [the California grid operator] to misallocate millions of dollars.” In case that was too subtle, the young job applicant went on to note that he had “showed how units in reliability areas can increase profits by 400%.”

There are a number of troubling assumptions this young man appears to be making: first, he appears to assume that no lawyer at JPMorgan will show this resume nor report the “flaw” to a Federal regulator. He also appears to believe that his ability to exploit electricity markets in California will be quickly embraced by JPMorgan personnel and cue his resume to the front of the line. And, finally, he seems to intuitively perceive that this is how Wall Street operates in general.

Stunningly, the new law grad was right on every one of his assumptions. Part of the same exhibit 76 is a JPMorgan email from the person who would become this young man’s boss, Francis Dunleavy, advising: “Please get him in ASAP.”

All of these related internal emails and the resume have been stamped by either JPMorgan or its lawyers as requesting confidential treatment if the public should file a Freedom of Information Act request, because the information is “privileged.”

Fortunately, Senator Levin is among a handful of Senators in Washington who understands that public scrutiny and a free press is all we have left as safeguards against Wall Street’s serial crimes and its captured regulators. Senator Levin placed the documents in the public domain, likely to the angry howls of multiple white shoe law firms employed by Wall Street.

Within three months of JPMorgan hiring the new law grad in July 2010, he was actively engaged in developing manipulative bidding strategies for JPMorgan in California electric markets. A few months later, the plan was deployed. By fall of the same year, JPMorgan was estimating that the strategy “could produce profits of between $1.5 and $2 billion through 2018.”

Three years later, on July 30, 2013, the gambit was exposed in a scathing report by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which included the names of JPMorgan personnel who were involved – effectively consigning their future career choices to companies with a penchant for exploiting flaws – in energy markets as well as human character.

Adding to the public’s cynicism of our current system of justice, no individual was charged in the matter and JPMorgan, which had company-wide profits of $18 billion in 2013, was let off the hook by FERC for $410 million in penalties and disgorgement.

The idea that FERC didn’t have enough evidence to charge individuals stood in stark contrast to what the government was alleging in a confidential 70-page internal document. In a May 3, 2013 front page article by Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Ben Protess of the New York Times, the reporters revealed that the government had stated in a written summary of its investigation that Cambridge University-educated Blythe Masters, the woman to whom Dunleavy reported and the ultimate head of JPMorgan’s Global Commodities Group, had “knowledge and approval” of the schemes that were carried out and that she had “ ‘falsely’ denied under oath her awareness of the problems.” According to the Times, the document also alleged that JPMorgan had “ ‘planned and executed a systematic cover-up’ of documents that exposed the strategy, including profit and loss statements.”

This recent Senate peek into the jaded atmosphere inside the expensive mahogany corridors of power on Wall Street comes on the heels of an endless stream of evidence that the Wall Street culture is decaying further rather than improving under the so-called Dodd-Frank reforms.

As Senator Levin’s two days of hearings were playing out on November 20 and November 21, Senator Sherrod Brown was receiving testimony as Chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection on how the New York Fed, a key Wall Street regulator, looked the other way at a Goldman Sachs deal that a Fed employee described as “legal but shady,” and then fired a bank examiner, Carmen Segarra, who refused to water down her critical examination of Goldman Sachs.

On Wednesday, March 14, 2012, Greg Smith, an Executive Director of Goldman Sachs, tendered his resignation to the firm in an OpEd in the New York Times, writing: “It makes me ill how callously people talk about ripping their clients off. Over the last 12 months I have seen five different managing directors refer to their own clients as ‘muppets,’ sometimes over internal e-mail,” Smith said. He called the current environment at Goldman “as toxic and destructive as I have ever seen it.”

Smith was far from the first to find the Wall Street culture untenable and make his findings public. In 2004, Nomi Prins, a highly respected former Managing Director at Goldman Sachs, wrote in her book, Other People’s Money: The Corporate Mugging of America:

“When I left Wall Street, at the height of a wave of scandals uncovering scores of massively destructive deceptions, my choice was based on a very personal sense of right and wrong…So, when people who didn’t know me very well asked me why I left the banking industry after a fifteen-year climb up the corporate ladder, I answered, ‘Goldman Sachs.’ For it was not until I reached the inner sanctum of this autocratic and hypocritical organization – one too conceited to have its name or logo visible from the sidewalk of its 85 Broad Street headquarters [now relocated to 200 West Street] that I realized I had to get out…The fact that my decision coincided with corporate malfeasance of epic proportions made me realize that it was far more important to use my knowledge to be part of the solution than to continue being part of the problem.”

Author Michael Lewis, who on March 30 of this year took to 60 Minutes to expose how Wall Street banks, stock exchanges and high frequency traders are rigging the stock market, wrote about his tenure at investment bank Salomon Brothers in the 1989 bestseller Liar’s Poker. According to Lewis, “It was assumed that I might well put a customer or two out of business. That was part of being a geek. There was a quaint expression when a customer went under. He was said to have been ‘blown up.’ ”

And in his 1997 bestseller, F.I.A.S.C.O. – Blood in the Water on Wall Street, Frank Partnoy sized up the culture of another Wall Street powerhouse, Morgan Stanley, where he had worked as a derivatives structurer, writing:

“…my ingenious bosses became feral multimillionaires: half geek, half wolf. When they weren’t performing complex computer calculations, they were screaming about how they were going to ‘rip someone’s face off’ or ‘blow someone up.’ Outside of work, they honed their killer instincts at private skeet-shooting clubs, on safaris and dove hunts in Africa and South America, and at the most important and appropriately named competitive event at Morgan Stanley: the Fixed Income Annual Sporting Clays Outing, F.I.A.S.C.O. for short. This annual skeet-shooting tournament set the mood for the firm’s barbarous approach to its clients’ increasing derivatives losses. After April 1994, when these losses began to increase, John Mack’s [President of Morgan Stanley] instructions were clear: ‘There’s blood in the water. Let’s go kill someone.’ ”

Corporations and financial systems that foster a culture of corruption are doomed to eventual collapse under the weight of that corruption. Shady schemes and outright crimes become the norm to seek profits and competitive advantage rather than honest ingenuity and innovation. Our country saw that clearly in 2008. What does it say about our collective sense of right and wrong or our nation’s staying power as a world leader when we seem to have learned nothing from the epic financial collapse that occurred just six years ago.