By Pam Martens: September 22, 2014

In 30 years of watching Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) debut on Wall Street, I have to say that I’ve never seen anything remotely resembling the Alibaba episode on Friday. It’s one for the record books not just in size but in opacity.

Alibaba is a Chinese e-commerce company whose large investment haul in the U.S. is not likely to brighten the tepid job prospects in this country one little bit. According to news out this morning, Wall Street underwriters exercised their option to boost stock in the deal by an additional 48 million American depository shares, bringing the IPO to the largest ever at $25 billion.

The company began trading publicly for the first time on Friday on the premier stock exchanging in the U.S., the New York Stock Exchange, which is supposed to exercise some degree of regimen over what it allows to be offered to the public under its shingle. The stock was priced at $68 and finished at $93.89 – a 38 percent gain on the day.

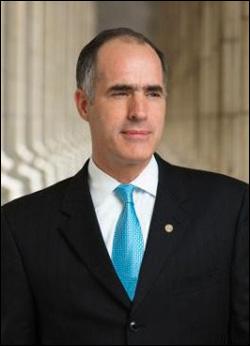

The concerns about this Chinese company’s opaque structure as a Variable Interest Entity (VIE) in the Cayman Islands are so serious that a U.S. Senator, Bob Casey (D-Pa), issued two letters this year to Mary Jo White, SEC Chair, demanding answers.

In a July 11, 2014 letter, Senator Casey drilled down to the core of the stock ownership problem, writing:

“…American investors in Chinese companies often do not enjoy the same protections and legal guarantees that they are afforded when they invest in American firms. Most Chinese firms that list in the U.S. use a structure known as a variable interest entity (VIE). VIEs are shell companies that give investors contractual claims to a firm’s profits but do not legally grant them ownership of the company. For example, according to Alibaba’s securities filing, Americans who invest in the company will not be buying stakes in Alibaba’s profitable e-commerce business, but in a related Cayman Islands shell company. These structures allow companies to circumvent Chinese regulatory restrictions on foreign investment.

“More concerning, given the Chinese government’s interest in restricting foreign ownership in certain industries, it is far from clear that the contractual claims underlying VIEs are enforceable. In fact, in recent years Chinese courts and arbitration boards appear to have invalidated VIE contracts and similar arrangements. As a result, VIE structures pose significant risks to American investors accustomed to the idea that shares sold on stock exchanges amount to legally sound ownership stakes in revenue-generating companies.”

The VIE structure for Chinese companies trading in the U.S. sounds more like an international lawsuit waiting to happen than an ownership piece of the corporate pie. If you think VIE shareholders have any right to elect the Board of Directors of this company, think again. Here’s a revealing section from the Alibaba prospectus:

“Risks Related to Our Corporate Structure

“The Alibaba Partnership and related voting agreements will limit your ability to nominate and elect directors.

“Our articles of association, as we expect them to be amended and become effective upon completion of this offering, will have the effect of allowing the Alibaba Partnership to nominate a simple majority of our board of directors…

“The interests of the Alibaba Partnership may conflict with your interests.

“The nomination rights of the Alibaba Partnership will limit your ability to influence corporate matters, including any matters to be determined by our board of directors. The interests of the Alibaba Partnership may not coincide with your interests, and the Alibaba Partnership or its director nominees may make decisions with which you disagree, including decisions on important topics such as compensation, management succession, acquisition strategy and our business and financial strategy.”

The history of Chinese companies listing here in the U.S. hasn’t exactly been a rose garden for investors either. Senator Casey notes the following in his July 17 letter:

“In the past three years alone, the SEC has charged a number of China-based companies with fraud, including China Sky One Medical Inc., AutoChina, SinoTech Energy Limited and China MediaExpress. The sheer number of fraud cases involving China-based companies listed in the U.S. reveals systemic problems with many Chinese companies’ legal structures and accounting practices. Indeed, earlier this year, SEC Administrative Law Judge Cameron Elliot ruled that the Chinese units of several large accounting firms could not audit U.S.-listed companies due to their willful failure to disclose information to U.S. financial regulators.”

In January of this year, Wall Street on Parade wrote about the frauds being perpetrated by Chinese reverse merger operators against U.S. investors. We ended the article with this question: “…if Chinese-based auditors will not honor U.S. laws for cooperating with securities fraud investigations and turning over audit documents, why do we still have $1.4 trillion of Chinese shares trading on U.S. exchanges?”

Just two days before Alibaba went public, Senator Casey wrote again to SEC Chair Mary Jo White, calling attention to the following:

“Like the reverse merger structure, the VIE structure is, by design, an opaque regulatory workaround. Paul Gillis, an expert on Chinese accounting practices at Peking University, has written that VIEs are ‘trying to tell Chinese regulators that the business is owned by Chinese and [tell] foreign investors that it is owned by foreigners.’ The nature of this structure puts Americans’ investment in VIEs at risk. Alibaba’s own SEC Form F-1 filing notes that if Chinese regulators deem their VIEs to be in non-compliance with Chinese law, the company could be ‘forced to relinquish our interest’ in those VIEs.”

Alibaba’s prospectus has this to say on the subject – not particularly reassuring, to put it mildly:

“It is uncertain whether any new PRC [People’s Republic of China] laws, rules or regulations relating to variable interest entity structures will be adopted or if adopted, what they would provide. If we or any of our variable interest entities are found to be in violation of any existing or future PRC laws, rules or regulations, or fail to obtain or maintain any of the required permits or approvals, the relevant PRC regulatory authorities would have broad discretion to take action in dealing with such violations or failures, including revoking the business and operating licenses of our PRC subsidiaries or the variable interest entities, requiring us to discontinue or restrict our operations, restricting our right to collect revenue, blocking one or more of our websites, requiring us to restructure our operations or taking other regulatory or enforcement actions against us. The imposition of any of these measures could result in a material adverse effect on our ability to conduct all or any portion of our business operations.”

And then there are the prospectus disclosures on potential conflicts of interests:

“The equity holders, directors and executive officers of the variable interest entities, as well as our employees who execute other strategic initiatives may have potential conflicts of interest with our company.

“…conflicts of interests for these individuals may arise due to dual roles both as directors and executive officers of the variable interest entities and as directors or employees of our company, and may also arise due to dual roles both as variable interest entity equity holders and as directors or employees of our company.

“We cannot assure you that these individuals will always act in the best interests of our company should any conflicts of interest arise, or that any conflicts of interest will always be resolved in our favor.”

The U.S. financial market, which collapsed just a mere six years ago under the weight of its own hubris, seems incapable of properly pricing risk. That should concern all Americans whose mutual funds and/or pensions are loading up right now on Alibaba with no idea of exactly what it is they’re buying.