By Pam Martens: August 25, 2014

The time and effort spent by members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors debating the timing of rate hikes is an utterly wasted exercise in futility – and the historically astute members of the Fed know it. After eight solid months of blathering about when rate hikes might occur, the real muscle in the bond market – the bond vigilantes – are drawing their own conclusions about what is coming down the pike.

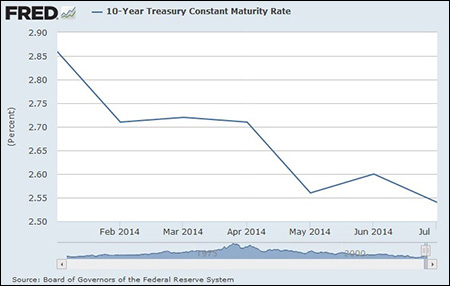

The benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note has moved from a yield of 2.85 percent at the beginning of the year to close last week at 2.38 percent. That’s the reaction of a market more worried about constrained income dispersal in the U.S. causing deflation than a market bidding up yields in anticipation of a rate hike.

In early August, the Fed’s own scholars released a report showing just how fragile the U.S. economy remains as a result of Wall Street’s continuing, institutionalized wealth transfer system. The Fed’s Division of Consumer and Community Affairs found that 52 percent of Americans would not be able to raise $400 in an emergency by tapping their checking, savings or borrowing on a credit card which they would be able to pay off when the next statement arrived.

As we have argued repeatedly at Wall Street On Parade, there is a finite equilibrium of income distribution at which the U.S. economy, or any other economy, can sustain momentum without artificial stimulus. In the U.S., 70 percent of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is consumption. When workers are stripped of an adequate share of the nation’s income, they cease to be the levers of economic growth.

Not a week goes by that we don’t hear about another retail chain closing stores; last week it was Staples announcing the closing of 140 stores while Sears reported it had lost $975 million in just the first six months of the year.

Wall Street’s institutionalized wealth transfer system is a core component of the crisis in income equality but the decimation of unions is a companion problem.

The late Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said it best: “Strong, responsible unions are essential to industrial fair play. Without them the labor bargain is wholly one-sided. The parties to the labor contract must be nearly equal in strength if justice is to be worked out, and this means that the workers must be organized and that their organizations must be recognized by employers as a condition precedent to industrial peace.”

According to 2013 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, union membership for all wage and salary workers stands at 11.3 percent but among private-sector workers it is a disastrously low 6.7 percent. According to an article last year by David Madland and Keith Miller at the Center for American Progress Action Fund, between 1967 and 2012, union membership in the U.S. fell from 28.3 percent of all workers to the current 11.3 percent “with significant drops observed in all 50 states.” The authors note further:

“This trend has been mirrored by the steady decline in the share of the nation’s income going to the middle 60 percent of households, which fell from 52.3 percent to 45.7 percent over the same time period. According to the newly released Census figures, neither measure showed any signs of reversing these troubling trends last year. Between 2011 and 2012, union membership declined even further, by 0.6 percentage points, while the middle class’s share of national income remained stagnant at 45.7 percent, its lowest level since data were first reported.”

On February 19, the International Monetary Fund warned of the risk of deflation, writing: “Low inflation raises the likelihood of a deflation in case of a serious adverse shock to activity.” Data from Bloomberg shows that the Personal Consumption Price Index, minus food and energy, rose a meager 1.2 percent in 2013, “matching 2009 as the smallest gain since 1955.”

Another great tragedy today is that the legions of academics flooding the Fed with research on which to base monetary policy have no historical perspective on Wall Street. They have never intensively studied the deflation of the Great Depression or Wall Street’s wealth transfer devices used then – and now – to concentrate the income of the nation in the hands of the top 5 percent.

And, based on all observable evidence, President Obama understands little about these matters either. That’s a dangerous condition for a President serving a nation in the aftermath of the greatest economic slump since the Great Depression.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on the other hand, had an immense grasp of the crisis of the 1930s, explaining publicly the root causes:

“…our basic trouble was not an insufficiency of capital. It was an insufficient distribution of buying power coupled with an over-sufficient speculation in production. While wages rose in many of our industries, they did not as a whole rise proportionately to the reward to capital, and at the same time the purchasing power of other great groups of our population was permitted to shrink. We accumulated such a superabundance of capital that our great bankers were vying with each other, some of them employing questionable methods, in their efforts to lend this capital at home and abroad. I believe that we are at the threshold of a fundamental change in our popular economic thought, that in the future we are going to think less about the producer and more about the consumer. Do what we may have to do to inject life into our ailing economic order, we cannot make it endure for long unless we can bring about a wiser, more equitable distribution of the national income.”

Amen.