By Pam Martens: July 21, 2014

The U.S. stock market looks more and more like that box of pasta on the grocer’s shelf. There’s less of it but it costs more.

According to data from Birinyi Associates, for calendar years 2006 through 2013, corporations authorized $4.14 trillion in buybacks of their own publicly traded stock in the U.S.

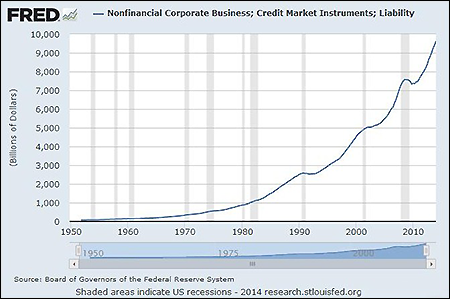

That should be good, right? Earnings are boosted on a per share basis because of fewer shares, making corporate prospects look brighter. Unfortunately, according to Standard and Poor’s, net equity issuance (the difference between buybacks, leveraged buyouts, etc. and Initial Public Offerings or secondary offerings) has been shrinking as corporate debt has been rising to fund those stock buybacks.

In 2013 alone, corporations authorized $754.8 billion in stock buybacks while simultaneously borrowing $782.5 billion from credit markets. Jeffrey Kleintop, Chief Market Strategist for LPL Financial reports that corporations are now the single largest buying source for all U.S. stocks and the swift pace of buybacks has continued into this year with Standard and Poor’s 500 companies buying back approximately $160 billion in the first quarter.

In addition to concerns over taking on corporate debt for reasons other than growing the franchise, investing in innovation, upgrading technology, etc. – there are also growing concerns over the use of dark pools to conduct these gargantuan share buybacks.

A dark pool is a private, unregulated trading venue that functions like a stock exchange by matching buyers with sellers – but it does so in the dark, without showing its bids and offers on stocks to the public. That has the potential for a great deal of price manipulation.

Starting with the week of May 26, 2014, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) began releasing weekly dark pool trading data to the public. That sliver of sunlight shows that some of the corporations with the largest share buyback programs are also among the heaviest traded stocks within the dark pools.

Several dark pools, also known as ATS or Alternative Trading Systems, openly woo stock buyback programs. Barclays, the firm that was just charged by the New York State Attorney General with falsifying data to customers about what was really going on in its dark pool, told Traders Magazine in September 2013 that its dark pool pitches its execution franchise to corporations with buyback programs:

“…when companies buying back shares meet with institutions in the firm’s alternative trading system, both sides of the transaction benefit. Having corporate buybacks handled by the electronic trading side of the firm gives Barclays an advantage over competitors…”

It’s safe to say that if Barclays is handling corporate share buybacks in its dark pool, other major investment banks are doing the same. Which raises yet another concern. How many hats can one Wall Street bank wear before it becomes a quagmire of conflicts?

Take the case of Apple Computer. According to FINRA data, in the five weekly periods of May 26 through June 23, dark pools traded over 103.6 million shares of Apple stock. The heaviest week was the week of June 9, 2014 when 39.9 million shares traded in dark pools. Goldman Sachs was responsible for trading 2,444,350 shares of Apple that week in its dark pool, Sigma-X, and has been in the top tier of dark pools trading Apple stock in all subsequent weeks reported by FINRA. (On July 1 of this year, FINRA administered a very mild wrist slap to Goldman Sachs for some very serious pricing irregularities in its dark pool.)

In addition to trading millions of shares of Apple stock each week behind a dark curtain, Goldman Sachs was the co-lead manager with Deutsche Bank in April of last year when Apple launched a $17 billion corporate debt offering in order to buy back its shares and increase its dividend. Apple’s $17 billion debt deal was the largest in history at that point. Later in the year, its debt record was dramatically overtaken when Verizon issued a $49 billion debt deal.

Goldman was also Apple’s advisor in 1996 when the company was warding off bankruptcy and Goldman managed its $661 million convertible debt offering.

At the time of Apple’s debt deal last year, its stock price had lost around 40 percent over the prior seven months as iPhone sales and other Apple products weakened. According to CNBC, referring to 2013, “Apple bought the largest number of shares ever in a single quarter, when it spent $16 billion on stock buybacks in the second quarter. It bought $4.9 billion in the third quarter.” Apple’s share price, which did a 7-for-1 stock split in June of this year, has almost fully regained its lost ground.

The problem with pampering shareholders with sweets financed by debt is that it can become a habit. One year after the April 2013 $17 billion debt deal, Goldman Sachs and Deutsche Bank co-led another $12 billion debt offering for Apple this year in April.

Goldman Sachs, under current market structure, can underwrite stocks and bonds for its customers; trade stocks in its own private stock exchange it runs behind a dark curtain; put out buy and sell recommendations that move stock prices up or down; co-locate its computer servers next to the computers of the regulated stock exchanges in order to get a speed advantage and an early peek at other traders’ orders; and, to round out the picture, it’s allowed to own and operate an FDIC-insured commercial bank where it can dole out lines of credit.

And, despite all this, Mary Jo White, Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, wants to be sure all Americans understand one thing – the stock market is not rigged.

Growth of Credit Market Debt at Non-Finance Related Corporate Businesses, October 1, 1949 to January 1, 2014