By Pam Martens: February 6, 2014

Some of the Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee sounded more like Wall Street lobbyists than legislators yesterday as they whined and moaned about the Volcker Rule, a provision of the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act; financial reform legislation that was enacted into law in 2010 by a duly held vote of their august body following the greatest financial collapse since the Great Depression. The Volcker Rule bans proprietary trading – trading for the house – unless it is a legitimate market making activity or a specifically aligned hedge.

While Wall Street On Parade is no fan of the revolving door executives at some of the key regulators, it has to be said that the patience exhibited by the regulators yesterday to suffer fools on this Congressional panel was, at least, a testament to their professionalism when appearing before the American public.

The regulators were regularly insulted by arrogant, self-serving questions showing fealty to the political campaign funders on Wall Street by a number of Republicans on the panel.

Setting the low mark for both arrogance and cluelessness was Congressman Bill Huizenga, a Republican from Michigan who, according to NPR, was elected to the House in 2010 with support from the Tea Party.

Huizenga lectured the regulators at length on his position that the Volcker Rule puts the U.S. at a competitive disadvantage globally. Huizenga made the incredibly uninformed statement that “there hasn’t been a problem with it here in the United States. I heard someone brought up the London Whale; alright, that’s a completely separate issue from what we’re dealing with here in the United States…”

Huizenga’s business background is in gravel pits in Michigan – it is clearly not in the commodities pits in Chicago or the trading floors of London and New York. Huizenga has been in the U.S. Congress for just three years. And, it was clear from his testimony that he has failed to read the exhaustive report on JPMorgan’s London Whale episode released by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in March of last year.

Huizenga’s sum total of knowledge about the London Whale appeared to be that it occurred in London, thus making it a “separate issue from what we’re dealing with here in the United States.” Perhaps Huizenga does not even know that JPMorgan Chase, the bank that carried out the disastrous London Whale trading, is a U.S. bank – the largest U.S. bank by assets residing at the top of the heap for another bailout if it fails.

Here’s the London Whale for Dummies version for Huizenga and his fellow head-in-the-sand colleagues:

According to testimony by Senator Carl Levin before the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations which conducted an in-depth investigation of the matter and issued a 300-page report, JPMorgan “piled on risk, hid losses, disregarded risk limits, manipulated risk models, dodged oversight, and misinformed the public.”

Each of those charges leveled by Levin has been occurring on a regular basis over the past decade in the proprietary trading divisions of the largest Wall Street investment banks. What elevated JPMorgan’s London Whale episode to DEFCON 1 by Senate investigators was the fact that JPMorgan was not gambling with its own money in its investment banking division. It was using insured deposits inside its commercial bank to carry out its high-risk, illiquid, do-or-die trading strategies.

JPMorgan has owned up to losing $6.2 billion on these failed trades. We don’t know the full extent of the losses because it simply stopped reporting them to the public.

According to exhibits released by the U.S. Senate along with its 300-page report on the London Whale episode, as of the close of business on January 16, 2012, JPMorgan’s Chief Investment Office, inside its commercial bank, held $458 billion notional (face amount) in domestic and foreign credit default swap indices. Of that amount, $115 billion was in an index of corporations with junk bond ratings.

If the London Whale traders had blown up JPMorgan Chase in 2012 by hiding and miss marking their losses (and the jury is out as to whether that might have happened were it not for other trading houses leaking what was going on to Bloomberg News and the Wall Street Journal, whose reporters admirably and aggressively jumped on the story and didn’t let go) Congress would have had another financial crisis on its hands just as the country was attempting to heal from the last disaster just four years prior.

Making Huizenga appear even more out of touch or an unabashed mouthpiece for Wall Street, was the fact that when Congressman Michael Capuano of Massachusetts asked each of the regulators appearing before the panel if they would repeal the Volcker Rule if they could, each of the five regulators present said “No.”

Even more telling, two of the five regulators specifically referred to the London Whale episode as the wakeup call for them.” Daniel Tarullo, a Governor of the Federal Reserve Board, said “no sir and I think, as many people have observed, the London Whale showed why.”

Thomas Curry, Comptroller of the Currency, said “I would agree with Governor Tarullo and for the same reasons. JPMorgan is a national bank. We supervise it. That was an eye opener.”

The exaggerated concern by some of the Republicans on this Committee about the loss of competitive advantage resulting from implementation of the Volcker Rule ignores another exhaustive study conducted at the request of Congress.

In February of last year, the General Accountability Office released a stunning analysis of the financial toll the 2007 to 2009 Wall Street financial crisis had on the U.S. economy and American workers. According to the GAO, cumulative output losses could exceed $13 trillion with another $9 trillion in losses in household wealth through declines in home equity – a combined tab of $22 trillion.

The study raised the serious concern as to whether the U.S. economy and many older workers can ever recover from the crisis. According to the report:

“Some studies describe reasons why financial crises could be associated with permanent output losses. For example, sharp declines in investment during and following the crisis could result in lower capital accumulation in the long-term. In addition, persistent high unemployment could substantially erode the skills of many U.S. workers and reduce the productive capacity of the U.S…CBO [Congressional Budget Office] reported that recessions following financial crises, like the most recent crisis, tend to reduce not only output below what it otherwise would have been but also the economy’s potential to produce output, even after all resources are productively employed…

“In a June 2012 working paper, International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists estimated the cumulative percentage difference between actual and trend real GDP for the 4 years following the start of individual banking crises in many countries. They found a median output loss of 23 percent of trend-level GDP for a historical set of banking crises and a loss of 31 percent for the 2007-2009 U.S. banking crisis. Other researchers who assume more persistent or permanent output losses from past financial crises estimate much larger output losses from these crises, potentially in excess of 100 percent of pre-crisis GDP.”

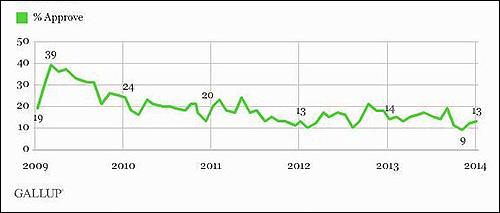

According to Gallup, Congress presently has an approval rating of just 13 percent from the American people. That’s slightly improved from its 9 percent approval rating in November of last year – an all time low.

A few more performances like yesterday from the likes of Huizenga and we’ll be crashing through the November lows in Congressional approval ratings in no time at all.