By Pam Martens: February 19, 2013

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has released a devastating appraisal of the financial toll the 2007 to 2009 Wall Street financial crisis has had on the U.S. economy and workers. According to the GAO, cumulative output losses could exceed $13 trillion with another $9 trillion in losses in household wealth through declines in home equity, bringing just those two areas of losses to potentially $22 trillion. The study notes that it can’t quantify losses in financial assets since the stock market has regained much of its lost ground but many people as well as portfolio managers of pensions and retirement assets locked in their losses by selling as the market dived.

The report indicates that the steep decline in home values during the financial crisis left homeowners collectively holding home mortgage debt in excess of the equity in their homes, marking a first since the data began being compiled in 1945. As of December 2011, the report said national home equity was approximately $3.7 trillion less than total home mortgage debt.

A key concern expressed throughout the study is whether the U.S. economy and many older workers can ever recover from the crisis. According to the report:

“Some studies describe reasons why financial crises could be associated with permanent output losses. For example, sharp declines in investment during and following the crisis could result in lower capital accumulation in the long-term. In addition, persistent high unemployment could substantially erode the skills of many U.S. workers and reduce the productive capacity of the U.S…CBO [Congressional Budget Office] reported that recessions following financial crises, like the most recent crisis, tend to reduce not only output below what it otherwise would have been but also the economy’s potential to produce output, even after all resources are productively employed…

“In a June 2012 working paper, International Monetary Fund (IMF) economists estimated the cumulative percentage difference between actual and trend real GDP for the 4 years following the start of individual banking crises in many countries. They found a median output loss of 23 percent of trend-level GDP for a historical set of banking crises and a loss of 31 percent for the 2007-2009 U.S. banking crisis. Other researchers who assume more persistent or permanent output losses from past financial crises estimate much larger output losses from these crises, potentially in excess of 100 percent of pre-crisis GDP.”

In contrasting this crisis to that of the Great Depression, the study notes that the monthly unemployment rate peaked at around 10 percent in October 2009 and remained above 8 percent for over 3 years, making it the longest stretch of unemployment above 8 percent in the U.S. since the Great Depression.

The toll on workers comes from a multitude of crisis-related outcomes: displaced workers — those who permanently lose their jobs through layoffs or plant closings – may experience an initial decline in earnings as well as longer-term losses in earnings. One study found that workers displaced during the 1982 recession earned 20 percent less, on average, than their non-displaced peers 15 to 20 years later. This can be a result of the stigma that some employers attach to long-term unemployment or the erosion of skills during the long period of unemployment. (Common sense suggests it might also be a result of accepting a lower wage job out of desperation.)

On April 25 of last year, the GAO released a study specifically looking at just the toll on workers. (GAO-12-445.) Among the findings:

-

Long-term unemployment rose substantially, and at a greater rate for older than younger workers. By 2011, 55 percent of unemployed older workers had been actively seeking a job for more than half a year (27 weeks or more).

-

Long-term unemployment can put older workers at risk of deferring needed medical care, losing their homes, and accumulating debt.

-

The GAO identified out-of-date skills, discouragement and depression, and inexperience with online applications as reemployment barriers for older workers.

-

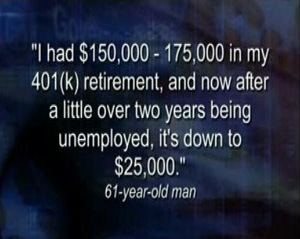

Long-term unemployment can substantially diminish an older worker’s future retirement income in several ways. First, it can force a worker to stop working and stop saving for retirement earlier than the worker had planned. Second, long-term unemployment can lead individuals to draw down their retirement savings to cover living expenses while they are unemployed, which was a common life experience described by GAO’s focus group participants.

-

GAO illustrated how a hypothetical worker who had $70,000 in retirement savings at age 55 and withdrew 50 percent of those savings during a 2 year period of unemployment, would need about another 5 ½ years of work and saving to rebuild the retirement account to the level it had been before unemployment began.

-

Long-term unemployment can motivate older workers to claim early Social Security retirement benefits, which will result in lower monthly benefits for workers and their survivors for the rest of their lives.

(You can listen to the actual audio clips from the GAO’s interviews with older workers and how they were impacted financially by the crisis here.)

There are many self-help techniques that older workers and retirees can implement to shore up their finances. We have a Personal Finance section devoted to educating Americans, without the hype and fictions from Wall Street. We also devised a 10-step plan to help yourself while helping your country recover.

The GAO study also looked at the potential cost of enacting the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation versus the cost of another financial meltdown. Since the dysfunctional structure of Wall Street prevents it from being adequately regulated, the GAO was wasting taxpayer money looking at this, in my opinion. Until the Glass-Steagall Act is restored, separating Wall Street casinos from insured deposit banks, the next $22 trillion crisis is an ever present danger no matter how much money is dumped into well-intentioned studies.

Dodd-Frank was passed in 2010 and yet many of the most important reforms, including the so-called Volcker Rule banning proprietary trading (trading for profits for the house) have yet to be implemented. GAO failed to place a figure on the overall cost of implementing Dodd-Frank but opined that the financial services industry may simply transfer the costs to their customers. The GAO also raised the old, reliable canard used so often by New York politicians like Chuck Schumer, worrying that the U.S. might lose its competitiveness in the global financial marketplace.

Given the open money funnel the U.S. government hooked up to Wall Street from 2008 through 2010, pumping trillions into insolvent, shady operators, it seems quaint to worry that Wall Street might leave these shores and move to London. Who else has an open purse the size of the New York Fed and allows Wall Street CEOs to sit on its Board.