By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 2, 2019 ~

There is a little noticed audio tape of an interview conducted on August 5, 2010 by investigators for the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC), a body convened under the Fraud Enforcement Recovery Act of 2009 to investigate the 2008 financial collapse on Wall Street. The interview is with Rodgin (Rodge) Cohen, Senior Chairman of Sullivan & Cromwell, the preeminent go-to lawyer on Wall Street.

Cohen makes a number of eyebrow-raising admissions during his interview. First, in response to a question, Cohen concedes that he was personally involved in the amendment contained in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (FDICIA) that changed the Fed’s emergency lending powers under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act.

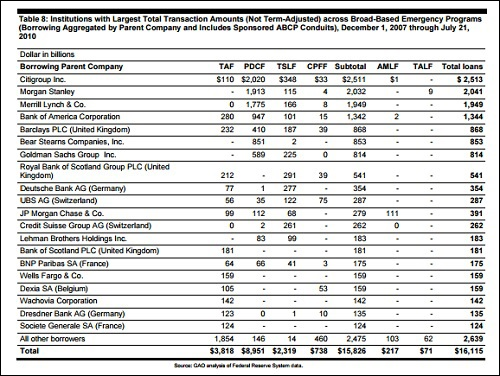

That one-sentence amendment to Section 13(3) was interpreted by the Federal Reserve from December 2007 to mid-2010 as giving it carte blanche to shovel $29 trillion in cumulative loans for as long as 2-1/2 years to Wall Street banks, broker-dealers, investment banks, hedge funds and foreign global banks, backstopped in many cases by dodgy collateral. In one of the Fed’s lending programs, the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), it made revolving loans totaling $8.95 trillion, a significant portion of which was based on accepting stocks and junk bonds as collateral at a time when the prices of both were in freefall. (See chart below.)

Cohen also admits that during his negotiations on behalf of the Board of Bear Stearns, he effectively provided a legal interpretation of the law to the Fed. Cohen stated during the interview: “We did say that we thought 13(3) provided broad power; that the ability was there if the Fed could satisfy itself on the collateral.”

In fact, all that the amendment to Section 13 says in the FDICIA legislation is this: “Section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. 343) is amended in the third paragraph by striking ‘of the kinds and maturities made eligible for discount for member banks under other provisions of this Act.’ ”

Cohen also concedes in the interview that his law firm represented major Wall Street beneficiaries of his interpretation of the law. In addition to the Fed’s extraordinary assistance to Sullivan & Cromwell clients Bear Stearns and AIG, other Sullivan & Cromwell clients that received extraordinary loans from the Fed under the Primary Dealer Credit Facility and other programs included Morgan Stanley, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs. (Just Morgan Stanley and Citigroup received revolving loans from the Fed totaling more than $4.5 trillion. See chart below from the audit conducted by the Government Accountability Office. The GAO audit did not cover all of the Fed’s secret lending programs. See the $29 trillion report from the Levy Economics Institute for the full panoply of assistance.)

The Federal Reserve, followed by a consortium of Wall Street firms, battled the media in court to prevent the public disclosure of those vast sums of lending by the Fed, which creates its money electronically at the push of a button. (See The Official Video from the Federal Reserve on How It Creates Electronic Money.)

In a preliminary draft report issued by the FCIC, it specifically mentions the involvement of Rodgin Cohen in the 13(3) amendment as follows: (The reference to Cohen was removed in the final report from the FCIC.)

“In 1991, Goldman Sachs and other large securities firms sought legislation that would give them greater access to the Fed’s emergency lending facility under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. Goldman and the other firms were concerned about ‘the absence of a safety net beneath Wall Street firms’ in light of (i) the reluctance of some commercial banks to provide credit to securities broker-dealers during the 1987 stock market crash, and (ii) the failure of Drexel in 1990. At the suggestion of H. Rodgin Cohen, a banking lawyer with Sullivan & Cromwell in New York City, the securities firms urged Congress to include an amendment to Section 13(3) in FDICIA.

“The enacted 1991 amendment to Section 13(3) authorized the Fed to make emergency loans to nonbanking firms as long as those loans are ‘secured to the satisfaction of the [Fed],’ and the amendment also gave the Fed broad discretion to accept almost any type of collateral from the borrowing firms.”

That last sentence above is a highly suspect interpretation of what the amendment to 13(3) actually allowed the Fed to do.

At the height of the financial crisis, the Wall Street Journal profiled Rodgin Cohen as follows on October 9, 2008:

“With virtually all of Wall Street as his client, [Cohen] has solidified his role as one of the most influential private-sector players in the financial crisis. Over the past five weeks alone, Mr. Cohen and his team have advised Fannie Mae, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., Wachovia, Barclays PLC, American International Group Inc., J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in a blitz of mergers, rescues and cash infusions.”

The year after the Section 13(3) amendment became part of the FDICIA, Anna Schwartz, then a Senior Research Fellow at The National Bureau of Economic Research, wrote a seminal paper on the dangers of this kind of tinkering. Schwartz wrote:

“Despite the restraint in the Act with respect to recapitalizing the FDIC, restraint is absent from another provision. The Act amended Section 13 of the Federal Reserve Act that deals with the Federal Reserve’s authority to discount for nonbanks. The amendment eliminated the requirement that the notes, drafts or bills tendered by nonbanks be eligible for discount by member banks. As interpreted by Sullivan & Cromwell, a New York law firm, for its clients in a memorandum of December 2, 1991, this provision enables the Fed to lend directly to security firms in emergency situations. Traditionally, commercial banks, knowing they had access to the discount window, have lent to brokerage firms and others short of cash in a stock market crash. It is not clear why the traditional practice was deemed unsatisfactory. In my view, the provision in the FDIC Improvement Act of 1991 portends expanded misuse of the discount window.”

Anna Schwartz passed away in 2012, after the details of the Fed’s $29 trillion interpretation of a one sentence amendment had come to light, giving new meaning to her concerns of 1992.

During Cohen’s interview with the FCIC, he is asked if the Fed’s financial assistance with Bear was the first time the Fed had used its 13(3) authority to help a nonbank. Cohen states that “To my knowledge it is the first time and the initial but fleeting reaction was we’ve never done it before, what sort of precedent are we creating for ourselves.”

It was not the first time the Fed had used 13(3) to assist a nonbank. It was simply the first time the Fed had showered money like a drunken sailor with an unlimited ATM card to the Fed’s discount window. According to a history provided by David Fettig, a Senior Advisor to the Minneapolis Fed, Section 13(3) “was used sparingly, and just 123 loans were made” from 1932 to 1936. The loans totaled $1.5 million – that’s $27.3 million in today’s dollars. The 1936 loans were the last time 13(3) was invoked until 2007.

It’s pretty easy to see that $27.3 million is to $29 trillion what a Treasury Note is to a CDO Squared. One is sane. The other is insane. Which might explain why the former Chairman of the Fed, Ben Bernanke, the former U.S. Treasury Secretary a/k/a the former Chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs Hank Paulson, and the former President of the New York Fed, Tim Geithner, who oversaw the majority of that $29 trillion binge, are currently on a roadshow with a pitchbook to the major media outlets portraying their actions as heroic firefighters during the crisis. Oh, and by the way, they want to remove the restraints that the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation placed on the Fed’s 13(3) ability to throw money at Wall Street in the next crisis.