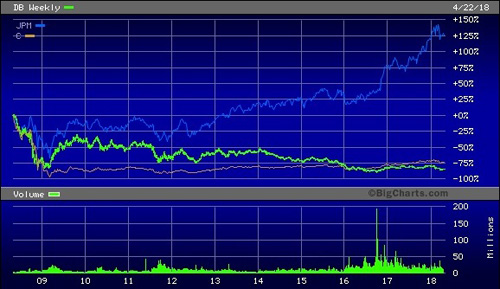

Deutsche Bank Chart (Green Line) Versus Citigroup (Orange Line) and JPMorgan Chase (Blue Line) Since 2008

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 26, 2018 ~

There is a great deal of hand-wringing in the U.S. media today over the plight of Deutsche Bank, the big German financial firm that has a hefty presence on Wall Street. Its first-quarter net profit slumped by 79 percent, it replaced its CEO of less than three years, John Cryan, this month with new CEO Christian Sewing whose game plan revolves around “painful” cuts.

On September 15, 2008, a key moment in the 2008 financial collapse on Wall Street when Lehman Brothers filed bankruptcy, Merrill Lynch was forced into the arms of Bank of America and Citigroup teetered toward insolvency, Deutsche Bank’s shares closed the day at $58.80 (equivalent price adjusted for a subsequent stock split). Yesterday, its shares closed at $14.60 on the New York Stock Exchange. Not only has it not recovered from the financial crash but it’s losing ground. Its shares are down a dramatic 21 percent in just the past 12 months.

With so much attention on Deutsche Bank’s woes, it’s curious that so little has been written about our own U.S. problem child – Citigroup (although we have certainly tried to make up for that here at Wall Street On Parade).

In 1998, with much media fanfare and cheerleading from the editorial page of the New York Times (for which it has since apologized) Citicorp CEO John Reed and Travelers Group CEO Sandy Weill announced they were merging the two firms. Citicorp at the time was the parent of the FDIC-insured Citibank while Travelers Group owned insurance companies, investment bank Salomon Brothers and the large retail brokerage firm, Smith Barney. At the time, the deal was in violation of the Glass-Steagall Act, the Depression era Federal law which barred firms that were primarily engaged in underwriting securities to affiliate with insured banks. The Bill Clinton administration would obligingly repeal the Glass-Steagall Act the year after the Citigroup merger and Clinton’s Treasury Secretary, Robert Rubin, would go on to make over $120 million sitting on the Board of the dysfunctional Citigroup over the next decade.

The Citigroup merger also forced the gutting of the provision in the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 that prohibited insurance companies from merging with insured depository banks. Removing those necessary banking walls proved lethal to the U.S. taxpayer, the U.S. economy, the U.S. housing market and the U.S. stock market. Just nine years after the repeals, Citigroup was on taxpayer life support, receiving the largest banking bailout in U.S. history. The U.S. Treasury infused $45 billion in capital into Citigroup; the Federal government guaranteed over $300 billion of Citigroup’s assets; the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits; and the Federal Reserve secretly funneled at least $2.5 trillion in cumulative, almost zero-interest-rate loans to units of Citigroup between 2007 and 2010.

When the Citigroup merger was announced in 1998, Reed and Weill were to function as Co-CEOs. That lasted until April 18, 2000 when Reed was forced out in a boardroom coup, leaving Weill the sole Chairman and CEO and on his way to becoming a billionaire from the lavish stock option grants he received from his head-in-the-sand Board of Directors.

On April 18, 2000, the day Reed stepped down, 100 shares of Citigroup were worth $6,212. Today, 18 years later, that 100 shares has shrunk to 13.33 shares with a value of $924.57. (Share count has shrunk because to bolster its trading price, Citigroup did a 1 for 10 reverse split on May 9, 2011, leaving shareholders with 1 share for each 10 shares previously held. It also did a 4 for 3 stock split on August 25, 2000.) Citigroup’s shareholder value has been decimated by 85 percent from Reed’s retirement to yesterday’s close, courtesy of those two men, both of whom were able to retire to luxurious lives and country estates despite putting together the worst banking concept of the century.

The rapidity with which Citigroup’s share price plunged during the financial crash in 2008 is likely a key reason that Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari is pounding the table for today’s Wall Street banks to hold more equity capital. We reported the following on November 28, 2008 regarding Citigroup’s price plunge: “Altogether, the stock lost 60 per cent last week and 87 percent this year. The company’s market value has now fallen from more than $250 billion in 2006 to $20.5 billion on Friday, November 21, 2008. That’s $4.5 billion less than Citigroup owes taxpayers from the U.S. Treasury’s bailout program.”

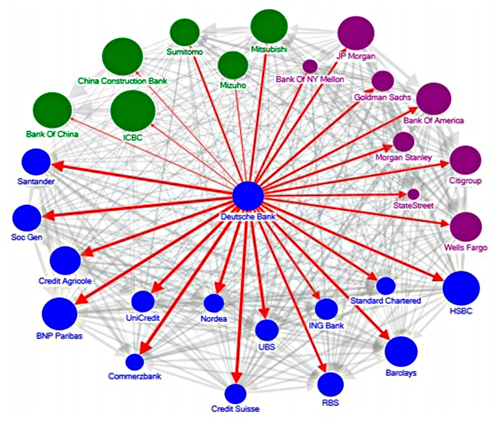

We saw in 2008 how weak links in the mega banking chain spilled out across Wall Street because of the invisible linkages to other banks and financial firms unknown to the public – like the fact that the big insurer, AIG, was the backer for tens of billions of dollars of credit default swaps while having no money to pay off the bets it had accepted from the biggest Wall Street firms. There is one report that raises similar alarm bells regarding Deutsche Bank.

In June of 2016 the International Monetary Fund (IMF) issued a report on the “Financial System Stability” of German financial institutions. The report specifically singled out Deutsche Bank as “the most important net contributor to systemic risks” and indicated that it had the potential to spill over to the U.S. The authors wrote:

“Notwithstanding moderate cross-border exposures on aggregate, the banking sector is a potential source of outward spillovers. Network analysis suggests a higher degree of outward spillovers from the German banking sector than inward spillovers. In particular, Germany, France, the U.K. and the U.S. have the highest degree of outward spillovers as measured by the average percentage of capital loss of other banking systems due to banking sector shock in the source country…

“Among the G-SIBs [Global Systemically Important Banks], Deutsche Bank appears to be the most important net contributor to systemic risks, followed by HSBC and Credit Suisse…The relative importance of Deutsche Bank underscores the importance of risk management, intense supervision of G-SIBs and the close monitoring of their cross-border exposures, as well as rapidly completing capacity to implement the new resolution regime.”

The chart below from the IMF report shows that Deutsche Bank spillover would impact every one of the largest banks on Wall Street, including Citigroup.

The IMF has not been the only entity to issue warnings about the continuing interconnectedness of the mega banks. The U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research was sounding similar alarm bells during the Obama administration – but it has gone strangely quiet under Trump who is pushing for deregulation.

Raising further questions about how competently and seriously Trump’s banking regulators will be attending to their duties comes the report yesterday that the head of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Joseph Otting, who is the primary regulator of national banks, was trading in financial stocks after he was nominated to that post.

Systemic Risk Among Deutsche Bank and Global Systemically Important Banks (Source: IMF — “The blue, purple and green nodes denote European, US and Asian banks, respectively. The thickness of the arrows capture total linkages (both inward and outward), and the arrow captures the direction of net spillover. The size of the nodes reflects asset size.”)