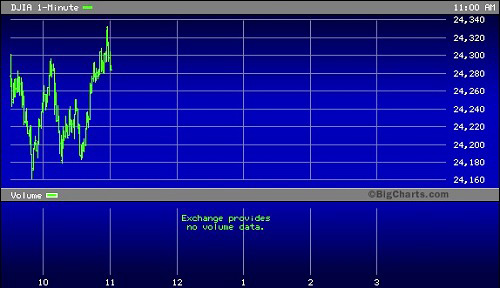

Trading in the Dow Jones Industrial Average Components on the Morning of Tuesday, March 27, 2018 Was Extremely Erratic

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: March 28, 2018

After experiencing carnage at the end of last week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 344.8 points yesterday or 1.43 percent of its value. But the tech-heavy Nasdaq closed down with a percentage loss of more than twice that amount at minus 2.93 percent.

Individual tech stocks far outpaced the losses in the broader market with Facebook closing down 4.90 percent; Alphabet (parent of Google) closing down 4.57 percent; Microsoft ending the session with a loss of 4.60 percent; Amazon down 3.78 percent; and Apple losing a more modest 2.56 percent.

Wall Street’s love affair with tech is rapidly turning into a “stormy” relationship. Back on August 27, 2015, we quoted Tan Teng Boo, the founder and CEO of Capital Dynamics, saying that just five U.S. stocks — Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon — are worth more than the Frankfurt, Germany stock market, which represents the fourth largest economy in the world.

At that time we checked his math and found on that day of August 27, 2015 the following market caps for the five stocks: Apple $625.532 billion; Google, $440.767 billion; Microsoft, $341.594 billion; Facebook, $245.795 billion and Amazon, $234.215 billion. The total market cap for the five — $1.889 trillion.

Since that time, a period of less than three years, Amazon has more than tripled in stock market value; Microsoft has more than doubled and the other three stocks have all added at least $200 billion each to their market value. The group stacks up as follows, resulting in a market cap at yesterday’s close of an astronomical $3.409 trillion for just five U.S. companies.

Closing Market Cap on August 27, 2015 versus March 27, 2018

Facebook: $245.795 billion versus $442.199 billion

Apple: $625.532 billion versus $854.159B

Google: $440.767 billion versus $699.436 billion (Alphabet, parent of Google)

Microsoft: $341.594 billion versus $688.90 billion

Amazon: $234.215 billion versus $724.733 billion

That $3.409 trillion market cap of those five companies is more than 10 percent of the total market capitalization of all 3,000 stocks in the Russell 3000. That index consists of the largest publicly traded companies in America as measured by market capitalization and represents approximately 98.5 percent of total market cap of all U.S. publicly held stocks.

According to the research from the Bespoke Investment Group, as of January 8, 2018 the market cap of the Russell 3,000 was $29.99 trillion. Bespoke also reports the following:

“From the low point of the Financial Crisis on March 9th, 2009, US stock market cap has grown from $7.6 trillion up to $29.99 trillion — easily the biggest creation of stock market wealth in history.”

The central question is how solidly was that wealth created? Was it created on the back of dubious tactics like borrowing billions of dollars to inflate a company’s stock through stock buybacks? Rana Foroohar’s book from 2016 comes to mind: In “Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Fall of American Business, Foroohar provides multiple examples of how “finance has transitioned from an industry that encourages healthy risk-taking, to one that simply creates debt and spreads unproductive risk in the market system as a whole.” In one case study, Foroohar examines Apple, and its use of share buybacks built on borrowed money. Foroohar writes:

“…Apple’s behavior is no aberration. Stock buybacks and dividend payments of the kind being made by Apple – moves that enrich mainly a firm’s top management and its largest shareholders but often stifle its capacity for innovation, depress job creation, and erode its competitive position over the longer haul – have become commonplace. The S&P 500 companies as a whole have spent more than $6 trillion on such payments between 2005 and 2014, bolstering share prices and the markets even as they were cutting jobs and investment.”

Economist Michael Hudson also looked at stock buybacks in his 2015 book, Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy. Hudson wrote:

“Instead of warning against turning the stock market into a predatory financial system that is de-industrializing the economy, [business schools] have jumped on the bandwagon of debt leveraging and stock buybacks. Financial wealth is the aim, not industrial wealth creation or overall prosperity. The result is that while raiders and activist shareholders have debt-leveraged companies from the outside, their internal management has followed the post-modern business school philosophy viewing ‘wealth creation’ narrowly in terms of a company’s share price. The result is financial engineering that links the remuneration of managers to how much they can increase the stock price, and by rewarding them with stock options. This gives managers an incentive to buy up company shares and even to borrow to finance such buybacks instead of to invest in expanding production and markets.”

The share buyback binge has continued in recent years, leading to an explosion in corporate debt which could make the next downturn particularly dicey. In April of last year, the International Monetary Fund released a study showing that the U.S. corporate sector had added $7.8 trillion in debt and other liabilities since 2010.

Last December, the Financial Times reported on a study from a Wall Street trade group, the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). The study found that if you added short-term company borrowings such as those found in money market funds to outstanding corporate debt, the total comes to a whopping $11.3 trillion. The article noted the following:

“Much of the debt sold by companies in recent years has been used to buy back their own shares, pay out higher dividends or finance big mergers and acquisitions. While these buybacks funded by cheap borrowing have boosted earnings, a missing ingredient has been spending on investment to build their businesses.”

Some of the smartest minds on Wall Street, like Nomi Prins, have concluded that this is not going to end well for investors. Wall Street On Parade has also cautioned, time and again, that this is no time for investors to be complacent about how much risk they have in their portfolios. We’d like to restate that position, strongly, again today.