By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 11, 2016

Why are the mega Wall Street banks throwing gasoline on the fire of this stock market rout?

Why are the mega Wall Street banks throwing gasoline on the fire of this stock market rout?

One of the damndest things in Wall Street history happened last week. No, we’re not talking about the Dow and S&P having the largest drop in the first week of the New Year in history, although that was certainly noteworthy. We’re talking about those mega Wall Street banks that can rarely bring themselves to put out a sell rating on a stock they follow, deciding to throw gasoline on a plunging stock market last week by issuing negative outlooks.

A cynical person (like someone who has just seen The Big Short movie) might be inclined to suspect that the Wall Street banks have gotten their short positions in place and are now ready to make some serious fast money.

Bloomberg News ran an article last Tuesday, in the midst of the rout, headlined: “Citi Has Cut U.S. Stocks to Underweight.” Citi is short for Citigroup, the mega Wall Street bank that crashed in 2008 and would have burned to the ground except for the largest taxpayer bailout in U.S. history. The article reveals this:

“In a note published on Monday, a team of Citi analysts led by equity strategist Robert Buckland pointed to the end of easing by the Federal Reserve as a key reason for the bank’s downgrade of U.S. equities.”

Citigroup’s prior executives currently sit as Secretary of the U.S. Treasury who also heads the Financial Stability Oversight Council (Jack Lew) and Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve (Stanley Fischer).

Also on Tuesday, CNBC reported to its wide cable audience that “Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s Stephen Suttmeier said the S&P is in danger of dipping below 1,965, a key technical level that could unleash a torrent of selling…Suttmeier warned that if the S&P 500 sinks below 1,965, then it may not bounce back — as it did in 2011 — and the market could reach lows of 1,870 to 1,820.”

JPMorgan Chase also jumped into the fray on Tuesday. CNBC carried an interview with Mislav Matejka, an Equity Strategist at JPMorgan Chase. Matejka had this to say:

“We were positive on equities for quite a long time. For seven years, we were saying to people, ‘You should be buying any dips.’ But we think structurally, this regime is coming to an end, and the regime that we should be having now is one of selling any rallies.”

It would be so very nice, even quaint, to think that mega Wall Street banks simply can’t bear to see their customers lose money. But then there’s the past seven years of billion-dollar settlements for alleged crimes against their customers not to mention felony counts and the very recent reminder in The Big Short movie that some of the biggest banks on Wall Street were failing to mark down the falling prices of subprime debt until they had gotten their own short bets in place. (Being short means you have made a bet that the security or derivative will lose money.) That part of the movie is based on the following text from the Michael Lewis book by the same name. “Burry” refers to Michael Burry, a real-life hedge fund manager:

“The first half of 2007 was a very strange period in financial history. The facts on the ground in the housing market diverged further and further from the prices on the bonds and the insurance on the bonds. Faced with unpleasant facts, the big Wall Street firms appeared to be choosing simply to ignore them…

“Then something changed – though at first it was hard to see what it was. On June 14, the pair of subprime mortgage bond hedge funds effectively owned by Bear Stearns went belly-up. In the ensuing two weeks, the publicly traded index of triple-B-rated subprime mortgage bonds fell by nearly 20 percent…

“On June 29, Burry received a note from his Morgan Stanley salesman, Art Ringness, saying that Morgan Stanley now wanted to make sure that ‘the marks are fair.’ The next day, Goldman followed suit. It was the first time in two years that Goldman Sachs had not moved the trade against him at the end of the month. ‘That was the first time they moved our marks accurately,’ he notes, ‘because they were getting in on the trade themselves…’

The real Michael Burry had this to say to New York Magazine’s Jessica Pressler in an interview at the end of last month when she asked where we stand economically today:

“Well, we are right back at it: trying to stimulate growth through easy money. It hasn’t worked, but it’s the only tool the Fed’s got. Meanwhile, the Fed’s policies widen the wealth gap, which feeds political extremism, forcing gridlock in Washington. It seems the world is headed toward negative real interest rates on a global scale. This is toxic. Interest rates are used to price risk, and so in the current environment, the risk-pricing mechanism is broken. That is not healthy for an economy.”

Interest rates are not the only mechanism used to price risk. Actual trades occurring in real-time on U.S. stock exchanges are used to price risk. Currently, a significant part of that trading is done in dark pools run by the mega banks rather than on exchanges, leaving the public in the dark about just how those trades are marked.

Then there are the Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) which are also tethered to the biggest banks on Wall Street.

If we took the above text from the Michael Lewis book about what was happening in 2007 and updated it to the facts on the ground today, it would read like this:

The second half of 2015 was a very strange period in financial history. The facts on the ground in the junk bond market, which had ballooned to over $1.8 trillion from about half that amount in 2008, diverged further and further from the prices of the junk bond ETFs. Faced with unpleasant facts, the big Wall Street firms appeared to be choosing simply to ignore them.

Then something remarkable happened. On December 10, 2015, Third Avenue Management announced it was blocking investors from withdrawing their money from its $788 million junk bond mutual fund which it planned to liquidate. The news was reported at 12:47 p.m. on December 10 by Bloomberg News and updated again at 3:06 p.m. In a market pricing junk bonds in real time, this news should have set off a major decline in junk bond ETFs. But it didn’t. For example, the Barclays High Yield Bond ETF (stock symbol JNK) closed down just 0.4 percent from its close the prior day.

There was more havoc in the junk bond market in December 2015 and continued calm pricing in junk bond ETFs. Last week, things got totally bizarre. The U.S. stock market, as measured by the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index and Dow Jones Industrial Index had its worst weekly start to the year in history. (Keep in mind that would include the Great Depression.) Big Wall Street banks did especially poorly with Citigroup off by 9.10 percent from its open on January 4 to its close on January 8 and JPMorgan Chase off by 7.87 percent over the same period.

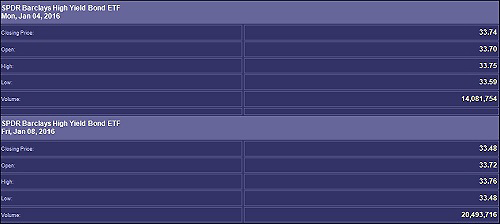

But, amazingly, the Barclays High Yield Bond Fund (JNK) was down by a negligible 0.65 percent from its open on January 4 to its close on January 8. (See charts below.) Are we really to believe that two of the largest Wall Street banks holding a big chunk of Americans’ insured deposits are riskier than junk bonds?

As Morningstar correctly notes, “Junk bonds tend to act more like stocks in their market behavior than other bonds. This is because the strength of junk bonds is connected to the strength of the company that issues them.”

So, in a week of a global stock market rout and economic tremors, we are asked to believe that a junk bond ETF sold off by a mere 0.65 percent.

It would seem that we are back to the mispricing era that exacerbated and deepened the last crash. Raise your hand high in the air and form a zero like Steve Carell in The Big Short movie. That zero represents the statistical probability that we are going to get out of this Frankenbank era without a major market breakdown.