By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 26, 2016

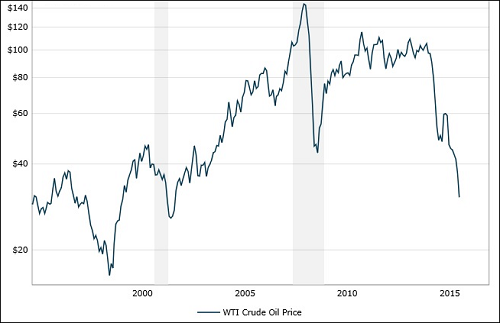

From June 2008 to the depth of the Wall Street financial crash in early 2009, U.S. domestic crude oil lost 70 percent of its value, falling from over $140 to the low $40s. But then a strange thing happened. Despite weak global economic growth, oil went back to over $100 by 2011 and traded between the $80s and a little over $100 until June 2014. Since then, it has plunged by 72 percent – a bigger crash than when Wall Street was collapsing.

The chart of crude oil has the distinct feel of a pump and dump scheme, a technique that Wall Street has turned into an art form in the past. Think limited partnerships priced at par on client statements as they disintegrated in price in the real world; rigged research leading to the dot.com bust and a $4 trillion stock wipeout; and the securitization of AAA-rated toxic waste creating the subprime mortgage meltdown that cratered the U.S. housing market along with century-old firms on Wall Street.

Pretty much everything that’s done on Wall Street is some variation of pump and dump. Here’s why we’re particularly suspicious of the oil price action.

Americans know far too little about what was actually happening on Wall Street leading up to the crash of 2008. The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission released its detailed final report in January 2011. But by July 2013, Senator Sherrod Brown, Chair of the Senate Banking Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection had learned that Wall Street banks had amassed unprecedented amounts of physical crude oil, metals and other commodity assets in the period leading up to the crash. This came as a complete shock to Congress despite endless hearings that had been held on the crash.

On July 23, 2013, Senator Brown opened a hearing on this opaque perversion of banking law, comparing today’s Wall Street banks to the Wall Street trusts that had a stranglehold on the country in the early 1900s. Senator Brown remarked:

“There has been little public awareness of or debate about the massive expansion of our largest financial institutions into new areas of the economy. That is in part because regulators, our regulators, have been less than transparent about basic facts, about their regulatory philosophy, about their future plans in regards to these entities.

“Most of the information that we have has been acquired by combing through company statements in SEC filings, news reports, and direct conversations with industry. It is also because these institutions are so complex, so dense, so opaque that they are impossible to fully understand. The six largest U.S. bank holding companies have 14,420 subsidiaries, only 19 of which are traditional banks.

“Their physical commodities activities are not comprehensively or understandably reported. They are very deep within various subsidiaries, like their fixed-income currency and commodities units, Asset Management Divisions, and other business lines. Their specific activities are not transparent. They are not subject to transparency in any way. They are often buried in arcane regulatory filings.

“Taxpayers have a right to know what is happening and to have a say in our financial system because taxpayers, as we know, are the ones who will be asked to rescue these mega banks yet again, possibly as a result of activities that are unrelated to banking.”

The findings of this hearing were so troubling that the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations commenced an in-depth investigation. The Subcommittee, then chaired by Senator Carl Levin, held a two-day hearing on the matter in November 2014, which included a 400-page report of hair-raising findings.

Of particular interest was the jaw-dropping physical oil assets owned by Morgan Stanley, an institution that most people viewed as an investment bank advising on mergers and acquisitions and a retail brokerage firm with over 15,000 brokers advising moms and pops and institutions on their investment portfolios. Levin’s Subcommittee unearthed the following about Morgan Stanley:

Morgan Stanley had purchased massive physical oil holdings, including the purchase of TransMontaigne, which managed almost 50 oil sites within the United States and Canada. It also had a majority ownership stake in Heidmar, which “managed a fleet of 100 vessels delivering oil internationally.” Morgan Stanley also owned Olco Petroleum, “which blended oils, sponsored storage facilities, and ran about 200 retail gasoline stations in Canada.”

The report raised further concerns as to just what Morgan Stanley had morphed into with this finding:

“One of Morgan Stanley’s primary physical oil activities was to store vast quantities of oil in facilities located within the United States and abroad. According to Morgan Stanley, in the New York-New Jersey-Connecticut area alone, by 2011, it had leases on oil storage facilities with a total capacity of 8.2 million barrels, increasing to 9.1 million barrels in 2012, and then decreasing to 7.7 million barrels in 2013. Morgan Stanley also had storage facilities in Europe and Asia. According to the Federal Reserve, by 2012, Morgan Stanley held ‘operating leases on over 100 oil storage tank fields with 58 million barrels of storage capacity globally.’ ”

Let that sink in for a moment. With financial derivatives and 58 million barrels of physical storage capacity, it might not be so hard to manipulate the oil market.

The Subcommittee got its hands on an internal Federal Reserve memo from 2011, which acknowledged that the Fed knew what a sprawling industrial octopus Morgan Stanley had become, even though the Fed had granted it bank holding company status during the 2008 crash and injected a cumulative total of $2 trillion in below market-rate loans into Morgan Stanley to help it survive the crash. The Fed memo said that Morgan Stanley “controls a ‘vertically-integrated model’ spanning crude oil production, distillation, storage, land and water transport, and both wholesale and retail distribution.”

According to the Subcommittee’s finding, Morgan Stanley “used its storage facilities to build inventories with millions of barrels of different types of oil.”

Morgan Stanley was not the only mega Wall Street bank singled out in the study. Among its numerous findings of fact were the following:

“Incurring New Systemic Risks. Due to their physical commodity activities, Goldman, JPMorgan, and Morgan Stanley incurred increased financial, operational, and catastrophic event risks, faced accusations of unfair trading advantages, conflicts of interest, and market manipulation, and intensified problems with being too big to manage or regulate, introducing new systemic risks into the U.S. financial system.

“Using Ineffective Size Limits. Prudential safeguards limiting the size of physical commodity activities are riddled with exclusions and applied in an uncoordinated, incoherent, and ineffective fashion, allowing JPMorgan, for example, to hold physical commodities with a market value of $17.4 billion – nearly 12% of its Tier 1 capital – while at the same time calculating the market value of its physical commodity holdings for purposes of complying with the Federal Reserve limit at just $6.6 billion.”

At another hearing on January 15, 2014, Norman Bay, the Director of the Office of Enforcement at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), explained how the rigging of the commodities markets might be conducted:

“A fundamental point necessary to understanding many of our manipulation cases is that financial and physical energy markets are interrelated…a manipulator can use physical trades (or other energy transactions that affect physical prices) to move prices in a way that benefits his overall financial position. One useful way of looking at manipulation is that the physical transaction is a ‘tool’ that is used to ‘target’ a physical price…The purpose of using the tool to target a physical price is to raise or lower that price in a way that will increase the value of a ‘benefitting position’ (like a Financial Transmission Right or FTR product in energy markets, a swap, a futures contract, or other derivative).

“Increasing the value of the benefitting position is the goal or motive of the manipulative scheme. The manipulator may lose money in its physical trades, but the scheme is profitable because the financial positions are benefitted above and beyond the physical losses.”

Wall Street mega banks are able to leverage their oil trades in the futures market by a factor of 95 to 1 or greater. Typically, margin of 5 percent or less is required of large oil speculators on the major commodity futures exchanges. If you know the direction of prices, you can make a killing using very little of your own firm’s capital. And if you also own the physical commodities, you can call yourself a bona fide hedger and avoid rules meant to rein in risky or manipulative trading.

Morgan Stanley has reduced its holdings of oil assets and storage capacity in recent years. Exactly how much remains is not known. In a November 2, 2015 press release, Morgan Stanley announced that it had completed the sale of its Global Oil Merchanting unit of its Commodities division to Castleton Commodities International LLC. The financial terms were not disclosed, however, the Financial Times reported that its Heidmar assets were not part of the deal.

The Federal Reserve, the sole regulator in the United States of bank holding companies, has known since at least 2009 that the mega Wall Street banks were building massive positions in physical commodities. It was that year that 60 Minutes revealed that Morgan Stanley had the capacity to store and hold 20 million barrels of oil and Goldman Sachs had taken stakes in companies that owned oil storage terminals – while both firms’ oil analysts made public statements that oil would reach $150 and $200 per barrel, respectively.

Now that Morgan Stanley has shed significant exposure to oil, its analysts are singing a different tune. Earlier this month on January 11, Bloomberg News reported that Morgan Stanley was predicting that “Oil is particularly leveraged to the dollar” and could potentially fall to $20.”