By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 17, 2015

In a properly functioning, rational, and efficient market, any form of Fed tightening after seven years of filling the punch bowl with an elixir of easy money should have been viewed by the markets as a contraction of monetary policy and sent both stocks and risky bonds plunging. But what we saw in the markets yesterday can only be described as bizarre.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, composed of 30 large cap stocks which are viewed as a barometer of the overall U.S. economy, soared 244 points by the close of trading. The Nasdaq, made up mostly of smaller companies than those in the Dow, which would have a harder time in a higher interest rate environment because their debt is rated lower generally, also soared and closed up 75.77 points.

A rise in interest rates should have sent utility stocks plunging since it is their dividend yields that attract investors and a hike by the Fed will make Treasuries and high grade corporate bonds more competitive to utility stocks. Instead of dropping, the Dow Jones Utilities Average closed up 2.73 percent.

Dow Transports, which have lost 1500 points in the past year as the economy lost steam and energy prices plunged, decided a Fed tightening is just the thing the economy needs to revive itself and closed up 1.80 percent.

But for whacko market reaction, nothing can compete with what junk bond (high yield) Exchange Traded Funds did yesterday. Flipping logic on its head, investors in two of the most popular junk bond ETFs decided that the perilous state of junk bonds would be enhanced by tighter credit conditions. (Just last week a junk bond mutual fund and a junk bond hedge fund shut down investor withdrawals of their money because of a lack of liquidity in the market.) Yesterday, the iShares iBoxx High Yield Corporate Bond ETF closed up 0.76 percent while the SPDR Barclays High Yield Bond ETF closed up 0.86 percent.

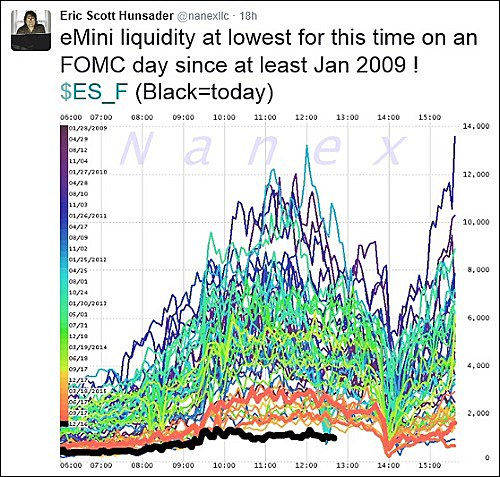

One possible explanation for the bizarre rally is that there was an overall absence of liquidity in the stock market yesterday as traders stood on the sidelines watching to see which way the market would react. In that void, it takes very little upside movement to frighten investors that are short the market, creating a big up spike from panic short covering. (We have previously reported on market moves of this nature in advance of Fed announcements.)

Eric Hunsader, the wise sage of this kind of behind the scenes action, posted a Tweet in advance of the Fed announcement yesterday, acknowledging that liquidity in the eMini futures contract on the Standard and Poor’s 500 index was the lowest on any Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announcement day since at least January 2009. With that kind of illiquidity, a few determined players can turn a market into their own special plaything.

In crazy market times like these, it’s comforting to do a reality check with those who have demonstrated an unwavering commitment to telling the public the truth, regardless of how unpopular truth might be on Wall Street. Fortunately for the public, James Grant, financial writer and founder of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, appeared on CNBC late yesterday afternoon to politely eviscerate the gushing headlines suggesting that the market rally meant confidence in the Fed and the U.S. economy.

Grant dropped these gems in answer to questions from Kelly Evans, co-host of CNBC’s “Closing Bell.” (Evans exudes a breath of fresh air on CNBC, feeding guests the tough questions that the public, rather than sponsors, would like answered. Evans had a previous career as a financial journalist at the Wall Street Journal where she penned the “Ahead of the Tape” column.)

Grant said that what the Fed had masterminded thus far with its zero-interest rate policy was the ability to push business failure out into the future, adding that “ultra low interest rates distort the allocation of capital, not just theoretically but in bricks and mortar and on Main Street.” As to why the Fed was raising rates now, Grant said it was to “save institutional face” since it had promised this move for so long and failed to act.

Grant likely stunned CNBC viewers with the assessment that the Fed will likely be moving rates back to zero, stating the following:

“I think that business activity which has been dwindling will continue to dwindle. And, it seems to me that the Fed will come face to face with the recognition that the stark fact is that it has raised its rate in the midst of the lowest growth environment in the past three rates hikes…I think there’s a chance that the Fed will be seen to have raised this rate at the start of a recession – that’s one possibility…It seems to me that as the evidence begins to mount that the economy is not in fact lifting off but rather continuing to dwindle, you’ll be seeing more talk and speeches from the Fed throwing up the possibility of due bouts of unconventional monetary action and some possibility for a move back to zero and I think that move will come.”

We are completely in the James Grant camp on the above points and we’d like to expand on his analysis above. Yellen and Company did not hike rates yesterday because they have any conviction that the U.S. economy is on the mend. The Fed, and particularly Yellen, who has to handle the tough questions from the Senate Banking and House Financial Services Committees, does not want to be excoriated by the Republicans on those Committees when the recession arrives and the Fed’s monetary gun is devoid of bullets.

To get an idea of what Yellen is thinking in that regard, consider this exchange that occurred between the Fed Chair and the Vice Chair of the Joint Economic Committee of Congress on December 3 of this year. Congressman Pat Tiberi, the newly appointed Vice Chair of the Joint Economic Committee asked Yellen what tools she would have if the U.S. enters a recession. At that point on December 3, the Fed could not cut rates because it was already at zero and its ability to engage in a new round of quantitative easing is highly problematic because it has already taken the hair-raising step of ballooning its balance sheet to $4.5 trillion as a result of its past three rounds of quantitative easing to resuscitate the economy to a subpar growth rate of between 1.5 and 2 percent. Despite this reality, Yellen responds as follows (see video clip below):

Yellen: “So, we have all of the tools that we’ve previously used to try to combat a recession. Uh, first of all if we had raised rates, we would have the possibility of lowering rates. Uhm, important to markets in setting or determining longer term yields is expectations about the future path of policy. For a number of years after rates had hit zero, uh, we discussed the reasons that we thought it would be appropriate to keep rates at low levels. As it turned out, seven years almost, now with zero rates. We discussed why we thought we would be keeping rates at low levels for a long time. And as the market absorbed the notion that they will stay low for a long time, longer term yields came down. Of course, we had asset purchases, we undertook substantial asset purchases in order to stimulate the economy. I think those purchases were successful as well in conjunction with that forward guidance and bringing down longer term rates and those tools are still available.”

While Yellen may be now talking rubbish to Congress, it’s important to remember that it was her predecessor chairs at the Fed, Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, who landed this mess in her lap, leaving her no choice but to talk rubbish to Congress and the American people in order to avoid a panic. But it’s not the job of business media to perpetuate this nonsense, unless they actually see their job as a propaganda medium. For example, the Wall Street Journal has this jewel of an assessment this morning:

“Global stocks surged on Thursday as investors around the world reacted positively to the Federal Reserve’s decision to raise interest rates and the confidence in the U.S. economy that underpinned the move.”

Investors and savers searching for the comfort of happy talk will likely come out of this unprecedented era both sadder and poorer — and angrier than ever at Wall Street and the Fed.