By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 2, 2015

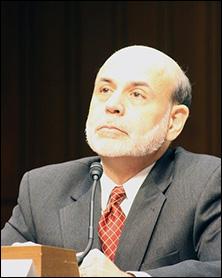

Last March, Wall Street On Parade reported that the appointment calendar of Ben Bernanke during his Chairmanship of the Federal Reserve in the years of the greatest financial crash since the Great Depression, showed 84 redactions of meetings he conducted with unnamed persons between January 1, 2007 through the collapse of Bear Stearns on the weekend of March 15-16, 2008.

According to the “official” record, those months were far from the core months of the financial crash, which are said to have been triggered with the collapse of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008 and the quick implosion of other major financial institutions that Fall.

Last month, Bernanke released a 600-page tome on the crash, The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and its Aftermath. (It’s not every day that an author credits himself with courage in a book title.) What particularly stands out in Bernanke’s telling of the crash is what he has chosen to leave out that would clearly challenge the “courage” narrative and infuse instead a hubris narrative.

Most Americans believe that the massive bailout of Wall Street began with the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), authorized by Congress after a second attempt and signed into law by President George W. Bush on October 3, 2008.

What few Americans remember is that a full year before TARP, Ben Bernanke’s Federal Reserve encouraged the largest banks in the U.S., and one foreign bank, to borrow from the Fed’s discount window – a source of borrowing traditionally reserved for desperate banks who cannot obtain cheaper sources of borrowing. The Fed provided the loans as 30-day, renewable loans rather than the traditional one-day loans. This action occurred on or about August 22, 2007. Bernanke writes as follows in his book:

“On Wednesday, August 22, Citi [Citigroup] announced it was borrowing $500 million for 30 days; JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and Charlotte, North Carolina-based Wachovia also announced that they had each borrowed $500 million. Our weekly report the next day showed discount window borrowing of $2.3 billion on August 22, up from $264 million a week earlier.”

What Bernanke does not mention in his book, as reported at the time by Reuters and the Financial Times of London, is that a foreign bank, Deutsche Bank of Germany, was at the same time borrowing from the U.S. Fed’s discount window.

This is a highly relevant topic today because a Presidential Candidate, Hillary Clinton, along with a raft of reporters and columnists, are arguing against the need to restore the Glass-Steagall Act (which would break up the largest banks and separate them from securities firms) because, they say, these commercial banks didn’t cause the 2008 financial collapse. Clearly, as even Bernanke concedes in his book, the financial crisis did not start with Lehman’s bankruptcy in September 2008 but with a spiraling global credit crisis that gathered steam beginning in August 2007.

Bernanke has also chosen not to include in his book as much as a whisper about the Federal lawsuit filed by Bloomberg News to unclench the details of that discount window borrowing during the crisis from the tight fist of the Fed. Only after the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation was signed into law, which left the worst aspects of Wall Street’s banking structure in place, were the details of the staggering sums the Fed was secretly loaning to banks made public – as a result of the Bloomberg lawsuit and legislation introduced by Senator Bernie Sanders. Senator Sanders is running against Clinton in the Democratic primary and arguing for the reinstatement of the Glass-Steagall Act.

Bloomberg News noted in this 2011 article the following:

“Bankers didn’t disclose the extent of their borrowing. On Nov. 26, 2008, then-Bank of America Corp. Chief Executive Officer Kenneth D. Lewis wrote to shareholders that he headed ‘one of the strongest and most stable major banks in the world.’ He didn’t say that his Charlotte, North Carolina-based firm owed the central bank $86 billion that day.

“JPMorgan Chase & Co. CEO Jamie Dimon told shareholders in a March 26, 2010, letter that his bank used the Fed’s Term Auction Facility ‘at the request of the Federal Reserve to help motivate others to use the system.’ He didn’t say that the New York-based bank’s total TAF borrowings were almost twice its cash holdings or that its peak borrowing of $48 billion on Feb. 26, 2009, came more than a year after the program’s creation.”

And, of course, there was Citigroup, parent of Citibank, which received the largest total sums of bailout assistance and which, insiders say, did not qualify for the loans because it was insolvent at the time. Newsweek wrote in December of last year that new details are still emerging as to how the New York Fed secretly propped up Citigroup, in part to cover up its own hubris as a regulator. The article notes further:

“The backdoor deal appears to have helped keep Citigroup, now America’s third-largest bank in terms of assets, out of the grave. Since the mortgage meltdown, it has managed to grow earnings and shed some toxic assets even though it continues to struggle with probes into its role in manipulating foreign currencies. But Citigroup has also ramped up its dealings in derivatives, a complex, risky bet that fueled the credit crisis during the 2008 collapse; the company had some $62 trillion in such contracts as of end-June 2014, up from $37 trillion in June 2009, according to data from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, another regulator.”

Tragically, as financial quakes begin to surface once again around the globe, the U.S. still finds itself with the Fed at the helm, regulating the largest and most systemically interconnected banks in the world.