By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 10, 2015

On Monday, Richard Berner worried aloud at the Brookings Institution about what’s troubling the smartest guys in the room about today’s markets.

Berner is the Director of the Office of Financial Research (OFR) at the Treasury Department. That’s the agency created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation to, according to their web site, “shine a light in the dark corners of the financial system to see where risks are going, assess how much of a threat they might pose,” and, ideally, provide the analysis to the folks sitting on the Financial Stability Oversight Council in time to prevent another 2008-style financial collapse on Wall Street.

Two notable concerns stood out in Berner’s talk. First was a concern about liquidity in bond markets evaporating rapidly for reasons they don’t yet “sufficiently understand.” Berner explained:

“…liquidity appears to have become increasingly brittle, even in the world’s largest bond markets. Although liquidity in these markets looks adequate during normal conditions, it seems to disappear abruptly during episodes of market stress, contributing to disorderly price changes. In some markets, these episodes are occurring with greater frequency. Examples include the mid-2013 sell-off in U.S. fixed-income markets, the October 2014 dislocation in U.S. Treasuries and futures markets, and the sharp moves in euro-area government bonds in early May of this year and in the past few days. None of these episodes disrupted U.S. financial stability, nor do we yet sufficiently understand their causes. But together they highlight a potential weakness in markets that could amplify the impact of financial shocks.”

Another major concern are the bond mutual funds and ETFs that have mushroomed since the 2008 crisis and are stuffed full of illiquid assets or assets which might become illiquid in a financial panic. Berner quoted SEC Commissioner Michael Piwowar on this issue, who has said:

“The growth of bond mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in recent years means that these funds now hold a much higher fraction of the available stock of relatively less liquid assets than they did before the financial crisis…their growth heightens the potential for a forced sale in the underlying markets if some event were to trigger large volumes of redemptions.”

Within 24 hours of Berner delivering his warnings, Bloomberg News was out with this nail biter:

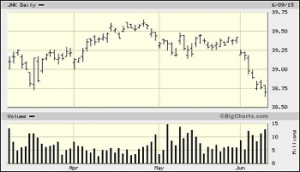

“BlackRock’s $14.3 billion high-yield bond ETF plunged 1.6 percent in the six days through Monday as $940.5 million exited the fund, Bloomberg data show. State Street Corp.’s $10.7 billion junk-debt ETF dropped 1.7 percent, with $571.7 million of withdrawals.”

The Financial Times threw more fresh worry into the bond market disarray this week by noting that the investment grade corporate bond market, which had heretofore held up “reasonably well” during the ongoing tumbles in government debt markets, has now joined the chaos. According to the Financial Times, “The average yield of debt issued by investment-grade companies has jumped from 2.8 per cent in mid-April to about 3.3 per cent, erasing investor gains made earlier this year.” (Bond prices move inversely to interest rates; when yields rise on existing bonds, their value falls in the market place.)

The Financial Times article noted the same concerns as those of the OFR, writing:

“Adding to the concerns of bond bears, the market’s liquidity — the ability of traders to buy and sell securities smoothly and without moving prices excessively — has diminished dramatically. That exacerbates sell-offs and could in the worst case turn a natural correction into a crash — especially if retail investors are frightened by the fact that their supposedly safe bond funds can lose money and dump the asset class.”

According to Bloomberg data, corporations have issued an astounding $9.3 trillion of bonds since the start of 2009 as borrowing costs have plummeted as the Fed cut and maintained its Fed Funds rate in the zero bound range. Much of the proceeds of those corporate bond offerings found their way into the stock market through corporate share buybacks, pushing stock prices artificially higher.

When you put all of these factors together, it’s clear this is an unprecedented era of risk with little visibility on how markets will behave during periods of extreme stress.