By Pam Martens: November 11, 2014

Apparently, not one of the global regulators pushing the latest plan to prevent another taxpayer bailout of the over-leveraged, globe-trotting banking behemoths that crashed the financial system in 2008 ever worked a day on Wall Street or sat behind a trading terminal during the crisis. If one had, he would have exposed this plan immediately as an exercise in illusory thinking – effectively, the same framework on which global banking currently exists.

Yesterday, the Financial Stability Board, established in 2009 to coordinate financial regulatory proposals on behalf of the Group of 20 major economies (G-20), released a proposal that is being promoted as a means of ending taxpayer bailouts of too-big-to-fail banks. These 30 banks are known as G-SIBs, or Global Systemically Important Banks. But the proposal does nothing to address the “systemic” danger of these banks, thus the proposal is nothing more than captured regulators floating another useless trial balloon for reform because they lack the political courage to admit the only solution is to break up these bloated financial institutions that regularly function variously as crime syndicates and institutionalized wealth transfer systems.

Mark Carney, head of the Bank of England, who also chairs the Financial Stability Board, touted the plan as a “watershed” moment.

The plan calls for the 30 global banks to hold somewhere between 16 to 20 percent of their risk-weighted assets in loss absorbing capital. In addition to issuing additional equity (which would be dilutive to existing shareholders), the plan calls for at least one-third of the new funding to consist of unsecured long-term debt held at the holding company level so that bond investors would experience the losses while other parts of the bank remain functioning if regulators have to place the bank in resolution.

Among the Global Systemically Important Banks are those the public continues to read about being charged with functioning in crime cartels: JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, and Barclays – adding an unaddressed dimension of systemic.

Under the plan, the global banks would have until 2019 to comply with the new requirements – which each country has the right to adopt, strengthen or reject outright. Right now, it’s all just a tentative proposal with public comment being solicited by emailing fsb@bis.org. The full proposal can be read here.

To fully grasp the magical thinking of this proposal, let’s reexamine what actually happens when a “systemic” bank begins to fail: (1) its counterparties, the other major banks, cut off lending and demand more liquid collateral to back the over-the-counter swap deals that the public and the regulators know nothing about. (2) Word of the bank’s troubles spread like wildfire and the share price (equity) goes into a collapse, burning rapidly through that layer of so-called “loss-absorbing capital.” (3) Because the bank has too much leverage on its balance sheet, it can’t raise cash rapidly enough to meet all of the collateral calls, leading to spreading concerns about the soundness of its trading parties, i.e., the other global banks. (4) All banks connected with it see a sell-off in their equity prices, bringing in the short sellers, who spread real, imagined or trumped-up rumors to drive prices lower. (5) In short order, the most bloated and troubled behemoths have no more liquid funds to pay depositors who make a demand for their demand deposits – which among the three largest banks in the U.S. are in the trillion dollar range, each. When you start to talk about trillions of dollars, there is no one but the taxpayer and the government who has that kind of an immediate backstop to stem the crisis.

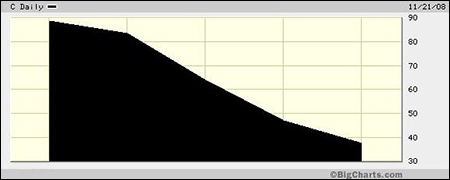

No better evidence exists of this indisputable reality than the meltdown of Citigroup’s equity capital, like a snow cone in July, during five trading sessions from November 17 through November 21, 2008. At that point, the bank had already borrowed $25 billion from the U.S. taxpayer along with the other usual bank suspects. In just five trading sessions, the bank (and its shareholders) lost 60 percent of their market value. (See the chart below for how too-big-to-fail actually functions in the real world.) By Friday, November 21, 2008, Citigroup’s market cap was worth $20.5 billion, which was $4.5 billion less than it already owed the taxpayer.

Citigroup’s bonds were no help because as Reuters reported at the time, “Prices of investment-grade bonds have fallen so far that their spreads already compensate for default rates worse than the Great Depression.”

These Wall Street mega banks are now holding hostage our nation, its economy, and the living standard of the next generation who will be left to deal with the mountains of debt taken on to deal with the financial collapse and its overhang. When six years of near zero interest rates can’t revive an economy to normal job creation and economic growth, it’s time to call our monetary policy what it is: a political masquerade to artificially prop up a failed, global banking business model.

It’s long past the time to break up the banks, restore the Glass-Steagall Act, and return sanity to deposit-taking banks.