By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 8, 2014

In July 2013 and again this past January, the U.S. Senate’s Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection, part of Senate Banking, convened hearings to get a handle on the extensive physical commodity holdings of Wall Street banks. At the January hearing, Senator Sherrod Brown, chair of the Subcommittee, told hearing participants that “the six largest U.S. bank holding companies have 14,420 subsidiaries, only 19 of which are traditional banks.”

At the time of the July 2013 hearing, Morgan Stanley, one of the nation’s largest retail brokerage firms, an investment bank, as well as an FDIC insured depository bank, owned sprawling crude oil operations. Congress had been aware of Morgan Stanley’s foray into the oil business since at least 2009 when 60 Minutes reported that Morgan Stanley had acquired the capacity to store 20 million barrels of oil.

Ostensibly as a result of the scrutiny, Morgan Stanley announced last December that it was selling its Global Oil Merchanting unit to a 100 percent subsidiary of Rosneft Oil Company, a large Russian crude oil producer. According to the press release Morgan Stanley issued at the time, the sale was to include an “international network of oil terminal storage agreements; inventory; physical oil purchase, sale and supply agreements; equity investments; and freight shipping contracts.”

According to Morgan Stanley, it was also transferring to Rosneft its 49 percent stake in Heidmar Holdings LLC, which manages pools consisting of a fleet of 100 oil tankers.

The deal was originally set to close in this year’s second quarter, then it moved to the third quarter. Now it’s the fourth quarter and the deal still hasn’t closed. In July the U.S. government imposed sanctions on Rosneft as a key player in the Russian economy, hoping to send a message to Moscow over its actions in the Ukraine.

On September 25, Dmitry Zhdannikov reported for Reuters that “Rosneft has enough cash to buy the Morgan Stanley unit, which sources said carries a price tag of between $300 million to $400 million. But to operate day-to-day, the business requires billions of dollars of bank lines of credit, funding that’s difficult to secure given the sanctions.”

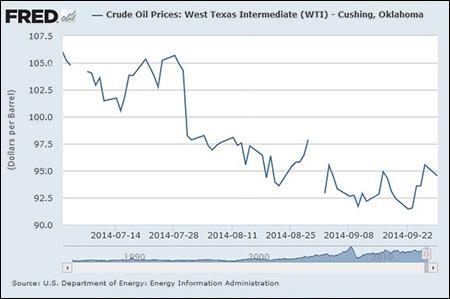

Being stuck in an oil deal that can’t close is not an ideal situation with crude oil in freefall and Saudi Arabia making overtures of waging an oil price war.

The roots of this physical commodities mess on Wall Street lead directly to the front door of the Federal Reserve. On October 2, 2003, the Federal Reserve issued a ruling that allowed Citigroup to massively expand its oil trading business by taking possession of crude oil on tankers. The Fed wrote that its action would “reasonably be expected to produce benefits to the public.” A stampede followed by other Wall Street firms. Federal Reserve Chairman, Alan Greenspan, voted in favor of the directive as did Ben Bernanke, who served on the Fed’s Board at the time.

But two major Wall Street firms are more equal than others in what they are allowed to do in the commodities sphere: Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs. At the Senate hearing in January, Michael Gibson, the Director of the Division of Banking Supervision and Regulation at the Federal Reserve, explained the details:

“Congress included a third provision in the GLB [Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act] Act that is relevant to the commodities trading activities of financial holding companies. Under section 4(o) of the Bank Holding Company Act, a company that is not a bank holding company and becomes a financial holding company after November 12, 1999, may continue to engage in activities related to the trading, sale, or investment in commodities that were not permissible activities for bank holding companies if the company was engaged in the United States in such activities as of September 30, 1997.

“This grandfather provision allows these activities up to 5 percent of the company’s total consolidated assets. In contrast to section 4(k) complementary authority, this authority is automatic — meaning no approval by or notice to the Board is required for a company to rely on this authority for its commodities activities. Also, unlike the firms subject to 4(k), the 4(o) grandfathered firms are able to engage in the transportation, storage, extraction, and refining of commodities. And, the cap on activities under section 4(o) is 5 percent of the firm’s total assets, while the cap on complementary activities is much lower at 5 percent of tier 1 capital. Only two financial holding companies currently qualify for these grandfather rights — Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.”

During the 2008 Wall Street crisis, both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley applied to become bank holding companies and were quickly approved as such by the Federal Reserve. That gave them immediate access to trillions of dollars in below market-rate loans from the Federal Reserve while leaving all their rights to engage in high-risk speculations in commodity markets, to own and store oil while also making wagers on it, intact.