By Pam Martens: February 20, 2014

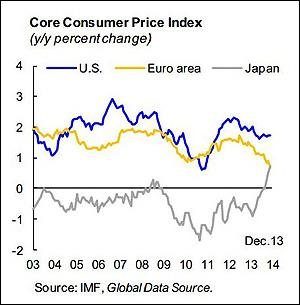

The IMF Released the Above Chart With Its Statement on February 19, 2014, Sounding a Warning on the Potential for Deflation

The U.S. government’s economic policy wonks are the habitual finger wags. They’ve lectured Japan incessantly for 20 years on how to beat its intractable deflation problem and in more recent years pointed at China for keeping its currency artificially low to boost exports. Last October 30, when the U.S. Treasury released its semi-annual “International Economic and Exchange Rate Policies” report to Congress, it turned its finger-pointing on Germany, grousing that:

“Within the euro area, countries with large and persistent surpluses need to take action to boost domestic demand growth and shrink their surpluses. Germany has maintained a large current account surplus throughout the euro area financial crisis, and in 2012, Germany’s nominal current account surplus was larger than that of China. Germany’s anemic pace of domestic demand growth and dependence on exports have hampered rebalancing at a time when many other euro-area countries have been under severe pressure to curb demand and compress imports in order to promote adjustment. The net result has been a deflationary bias for the euro area, as well as for the world economy.”

Wagging the finger at Germany because it lacks sufficient altruism toward its economically struggling neighbors is certainly cheeky from the country whose reckless and misguided deregulation of Wall Street mega banks created the 2008 financial collapse which then played a central role in destabilizing the world economy.

Given this backdrop, it was noteworthy that yesterday the International Monetary Fund (IMF) pointed its own finger squarely at the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, in its statement on “Global Prospects and Policy Challenges” prepared for the upcoming G-20 meeting of finance ministers and central bank governors in Sydney, Australia on February 22 and 23.

To understand what the IMF is actually signaling requires a quick review of central bank jargon versus public jargon. Central bank flooding of the financial markets through bond purchases in hopes something will stick in terms of job creation, economic growth, and longer term financial stability is referred to as quantitative easing or QE by the general public. The U.S. Federal Reserve prefers the more scholarly LSAP or Large Scale Asset Purchases. Not to be outdone, the IMF has its own acronym, UMP, for Unconventional Monetary Policy. Regardless of the chosen phrase, no one is sure how all of this unconventional meddling is going to end, although at least three Republican Senators suspect it is akin to either a morphine drip, disguising chronic pain and a seriously ill patient, or leading the financial markets into a “sugar high” complacency as another asset bubble forms.

Clearly pointing to the fact that the Federal Reserve has made two separate announcements of cutting back its bond purchases by $10 billion a month (a total of $20 billion), the IMF warned: “Advanced economies should avoid premature withdrawal of monetary accommodation as fiscal balances continue consolidating.”

The IMF is clearly worried about the onset of the kind of intractable deflation that plagued the U.S. and the global economy during the Great Depression of the 30s. That is also what kept former Fed Chairman, Ben Bernanke, up at night. While the Fed has numerous monetary tools to whip inflation, when your short-term interest rate is already at the zero-bound range and you’ve racked up a $4 trillion balance sheet from your prior QE-LSAP-UMP monetary experiments, the monetary tools to battle deflation are scarce.

This is specifically what is worrying the IMF:

“Capital outflows, higher interest rates, and sharp currency depreciation in emerging economies remain a key concern and a persistent tightening of financial conditions could undercut investment and growth in some countries given corporate vulnerabilities. A new risk stems from very low inflation in the euro area, where long-term inflation expectations might drift down, raising deflation risks in the event of a serious adverse shock to activity. Further action and cooperation are needed to promote financial stability and robust recovery…Given still large output gaps, very low inflation, and ongoing fiscal consolidation, monetary policy should remain accommodative in advanced economies. There is scope for better cooperation on unwinding UMP, including through wider central bank discussions of exit plans. In the euro area, repairing bank balance sheets remains critical to monetary policy transmission. Finally, fiscal consolidation should proceed at a measured pace, while preserving the long-run growth potential of the economy.”

On October 3 of last year, John C. Williams, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, delivered some very astute observations on the impact of the Fed’s bond purchases, noting that when it first began this process in 2008, it had “no first-hand experience with such policies.” Williams continues:

“The evidence to date provides support for the view that financial markets are segmented and that asset purchase programs affect interest rates and other asset prices. There have been numerous studies of the effects of our asset purchases on longer-term interest rates. This analysis suggests that each $100 billion of asset purchases lowers the yield on 10-year Treasury notes by around 3 to 4 basis points, that is between 0.03 to 0.04 percentage point. That might not sound like much. But consider the Fed’s so-called QE2 program in 2010-11 that totaled $600 billion of purchases. According to estimates, that program lowered 10-year yields by about 20 basis points. That’s about the same amount that the 10-year Treasury yield typically falls in response to a cut in the federal funds rate of ¾ to 1 percentage point, which is a big change. Applying the same logic to the current, much larger, asset purchase program, the implied reduction in longer-term interest rates is roughly 40 to 50 basis points.”

The IMF clearly understands the flip side of the above scenario, writing:

“Many emerging markets came under renewed financial pressure in the second half of January — equities fell, spreads rose, and currencies of major economies depreciated. Markets appear to be reassessing emerging market fundamentals as global conditions change. While the pressures were relatively broad-based, countries with higher inflation and current account deficits were amongst the most affected (Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, and South Africa). The sell-off came against the backdrop of several negative factors in some countries and weakening sentiment toward emerging economies. Specifically, China’s shadow banking and weaker-than-expected PMI data, continued or rising political tensions (Thailand, Turkey, South Africa, and Ukraine), and Argentina’s depreciation, all contributed to the negative sentiment against the broader context of continued Fed tapering.”

Janet Yellen, who took the reins at the Fed just this February 3, is no doubt thinking at this moment: “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”