By Pam Martens: January 25, 2013

Working on Wall Street for over two decades, I often heard financial advisors tell their clients that a good rule of thumb to determine how much of their investment money to put into stocks was to subtract their age from 100 and put the difference in stocks. For example, if your age is 54, subtract 54 from 100 and put the difference, 46 percent, of your investable money into stocks. If your age is 30, by this formula 70 percent of your funds would go into the stock market.

The overall theory is sensible: the older you are, the less risk you should take because you will not have enough earning years left to replace lost funds.

The high percentages recommended, however, felt like a formula cooked up by Wall Street to coax more money into the market. As with most things peddled on Wall Street, I never bought into this nonsense. Suggesting that anyone put 50 or 70 percent of their life savings into the stock market seemed like irresponsible advice to me.

As Wall Street has grown more corrupt over the years and financial statements for publicly traded companies have become more inscrutable, it isn’t at all clear if one is buying stocks or throwing down dice on a casino table.

If you are an investor who is not emotionally prepared to lose 22 percent of your money in one day (October 19, 1987, Dow Jones Industrial Average loss) or 38.5 percent in one year (2008 S&P 500 loss), just stay completely away from stocks or invest only an amount you can afford to lose. Many people do just that and live happy ever after.

People who are not emotionally prepared to see large declines in their principal will invariably buy at the top and then panic and sell into a sharp decline. They are better off not investing in stocks.

Sure, you’ve probably heard many times that if you want growth you buy stocks and if you want income you buy bonds (fixed income). But there’s another way to achieve growth: under spend the income you’re receiving on your bonds and buy more bonds with the excess interest income. That will give you growth of principal and eventually more income that can be tapped in twilight years.

When Treasury notes and bonds once again have attractive yields, they’re a good choice for the risk-adverse investor, using short and intermediate maturities to lessen price fluctuation prior to maturity. Despite what you hear about the national debt, the U.S. government made it through the Great Depression with no defaults on its notes and bonds and retains the best guaranty of all to make its interest payments: the unlimited ability to tax all of us.

If you’re reaching for extra yield in corporate bonds, be very careful. Corporate bonds have been known to plunge in value when the financial filings of the company come into question. That has been a growing occurrence over the past 15 years.

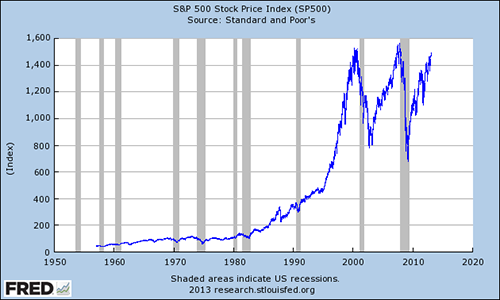

The chart below of the Standard and Poor’s 500 index of stocks should give one pause. The plunging lines since 2000 are dramatic and the second decline line set a lower low than the prior. That’s typically not a good sign. Let the buyer beware.

————-

Pam Martens, the Editor of Wall Street On Parade, managed the life savings of average Americans for 21 years on Wall Street. Her personal finance columns seek to help the public better understand the jargon, complexities, and conflicts of Wall Street. The information that appears on this site cannot, and does not, take into account your particular investment goals, your unique financial situation or income needs and is not intended to be recommendations appropriate for you. When it comes to making your own investment decisions, you should always consult in advance with your financial advisor and accountant.

At times, Wall Street On Parade links to news or opinion on other sites which we believe to be in the public interest. These web sites may also contain investment advice or investment advertising. We receive no remuneration for these links, provide them purely in the public interest, and are not endorsing or recommending any investment information that may appear on the site.