By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 5, 2019 ~

The Fed is in deep fear, while also in deep denial, about what happened last December. Its fear is that it could happen again this December. Its denial is that its lax supervision of the Wall Street mega banks is largely responsible for the mess.

The stock market news on December 24 of last year was not what folks want to be reading about on Christmas Eve. The Dow Jones Industrial Average had plunged 653 points on Christmas Eve and headline writers across major media were declaring the month to have been the worst December for stocks since the Great Depression.

But the declines in the broader stock market averages paled in comparison to the December carnage that occurred in the share prices of the mega banks on Wall Street and, to the Fed’s consternation, the insurance companies that are stealthily interconnected to the mega banks as their derivative counterparties.

Despite all of the warnings that have come out of the Office of Financial Research (OFR), and the implosion of the giant insurer, AIG, during the financial crisis as a result of its derivatives ties to the big Wall Street banks, the Federal Reserve has not reined in these interconnections.

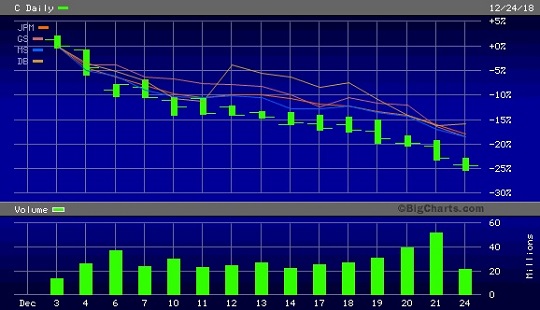

The two charts below show the companion collapses in December in the share prices of the Wall Street banks with the heaviest exposure to derivatives and the insurance companies serving as counterparties to those derivatives. (Banks are also derivative counterparties to each other.)

Among the big banks, Citigroup fared the worst. On Monday, December 3, 2018 Citigroup closed the day with a stock price of $65.16. By Christmas Eve, December 24, 2018, the mega Wall Street bank had lost 24 percent of its share price, closing at $49.26.

Citigroup was the poster child for the Fed’s bungling supervision in the leadup to its collapse in 2008. It became a penny stock in 2009. Secretly, without any approval or hearings in Congress, the Fed pumped $2.5 trillion in below-market-rate, revolving loans into Citigroup from December 2007 through at least the middle of 2010 to resuscitate the serially-charged bank. (The Fed’s loans became public after the Government Accountability Office released the results of its audit of the Fed’s loans in 2011.) Citigroup did not, however, change its jaded ways and was forced to admit to a felony charge in 2015 for its role in rigging foreign currency markets. (See A Private Citizen Would Be in Prison If He Had Citigroup’s Rap Sheet.)

Among the swooning insurers, Lincoln National and Ameriprise Financial lost more than 20 percent while MetLife lost 14 percent between Monday, December 3, 2018 and the close on Christmas Eve. All three insurers are connected to the Wall Street banks via derivatives.

We know which insurers have exposure to risky derivative gambles with the Wall Street banks because the 2017 Financial Stability Report from the Office of Financial Research, the Federal agency created under the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, named them. Those U.S. insurers are: Ameriprise Financial, Hartford Financial Services Group, Lincoln National Corp., Prudential Financial, Voya Financial, MetLife and – wait for it – AIG, the very same insurer that got bailed out to the tune of $185 billion during the financial crisis.

While MetLife did not require the level of bailout funds provided to AIG during the financial crisis, the Financial Stability Oversight Council reported that MetLife was regularly helping itself to the bailout trough during the crisis, writing the following:

“During 2008 and 2009, MetLife’s subsidiary bank accessed the Federal Reserve Term Auction Facility 19 times for a total of $17.6 billion in 28- day loans and $1.3 billion in 84-day loans. In March 2009, MetLife raised $397 million through the Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program run by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which enabled the organization to borrow funds at a lower rate than it otherwise would have been able to obtain. Additionally, MetLife borrowed $1.6 billion through the Federal Reserve’s Commercial Paper Funding Facility.”

The decline in the stocks of the banks and the insurers got so dicey in December of last year that by Sunday, December 23, U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin publicly announced that he had “conducted a series of calls today with the CEOs of the nation’s six largest banks: Brian Moynihan, Bank of America; Michael Corbat, Citigroup; David Solomon, Goldman Sachs; Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan Chase; James Gorman, Morgan Stanley; and Tim Sloan, Wells Fargo.” According to Mnuchin, the banks all assured him that they had “ample liquidity.”

Mnuchin then went a step further. He announced that on Monday, Christmas eve, he would be convening a joint call with the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, the FDIC, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. His statement about this call said “These key regulators will discuss coordination efforts to assure normal market operations.”

The Dow proceeded to tank 653 points on the day of that call, figuring that if such a call was needed things must be worse than suspected.

Exactly what those “coordination efforts” were nobody knows. But the Dow climbed from 21,792 on December 24, 2018 to 26,258 by the close of trading on April 1, 2019 – a move of 4,466 points in a little more than three months.

One notable action was that the Federal Reserve, which had hiked rates by one-quarter point four times in 2018, stopped hiking rates. It has cut rates by one-quarter point three times so far this year; it is now offering $690 billion a week in super-cheap loans to Wall Street securities firms (primary dealers); and it’s returned to quantitative easing (which it doesn’t want you to call by that name), buying up $60 billion a month in Treasury bills while simultaneously crediting that amount each month to the banks’ liquid reserves at the Fed.

All of this raises the reasonable question as to whether Wall Street stock prices are driving central bank monetary policy. If that is the case, and it clearly seems to be, there is not only systemic risk in the safety and soundness of U.S. banks but systemic risk in the level of debt that the Federal Reserve is prepared to take on to bail out Wall Street – for the second time in a decade. Ultimately, the U.S. taxpayer is on the hook for all debts owed by both the Federal government and the Federal Reserve.

Citigroup Stock Price Chart (Green) Versus JPMorgan (JPM), Goldman Sachs (GS), Morgan Stanley (MS) and Deutsche Bank (DB) — December 3, 2018 through Christmas Eve 2018