By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: May 24, 2019 ~

Most stock owners of J.C. Penney never thought they’d see the day when it traded as a penny stock. But that’s what happened yesterday when shares of the large retailer closed at 91 cents, a loss of 9.79 percent on the day. The macro picture is that J.C. Penney employs 95,000 people and operates 864 stores across the United States. Its future will have an impact on jobs and commercial real estate prices in the United States. At 91 cents a share, those prospects aren’t looking too good right now.

The broader markets fared better than J.C. Penney yesterday but were, nonetheless, a sea of red. After being down more than 400 points intraday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed with a loss of 286 points or 1.11 percent at 25,490. The Nasdaq, laden with tech losers, lost 122.5 points or 1.58 percent to close at 7628. The big Wall Street bank stocks fared worse than the Dow on a percentage basis with every mega bank in the red. And, as we have been pointing out for some time, the big insurance companies in the U.S. traded in correlation with the mega banks yesterday as a result of their dangerous ties as derivative counterparties. (Think AIG and its $185 billion bailout as a result of its derivative contracts with Wall Street in 2008.) Hit particularly hard yesterday was the insurer, Lincoln National, which lost 3.08 percent on the day.

Oil was another pivotal mover yesterday. The ongoing trade war with China is sending a signal to the markets that there will be a global economic slowdown which means less manufacturing activity and, thus, less demand for crude. The U.S. domestic crude, West Texas Intermediate, for July delivery lost 5.7 percent on the New York Mercantile Exchange to close at $57.91. That took its price below its 200-day moving average, an ominous signal to technical analysts.

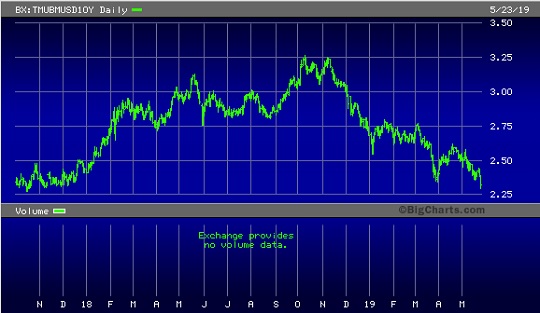

Action in the 10-year U.S. Treasury Note also signaled concerns about an economic slowdown in the United States. In intraday trading, the 10-year touched a yield of 2.29 percent, its lowest level since October 2017. (See chart above.) Declining yields on the 10-year note are not compatible with a robust economy which would produce inflation worries and higher interest rates. Declining yields are symptomatic of an economic slowdown which would result in less demand for money and, thus, lower interest rate costs for borrowing.

Adding to the prognosis for a slowdown, the yield curve inverted yesterday with the 10-year yield falling below that of the 1-year Treasury. As of 7:21 a.m. this morning, there was, just barely, a return to a positive yield curve with the 1-year Treasury yielding 2.31 percent and the 10-year at 2.33 percent.

No matter how you slice it, those are bizarrely low yields for this point in an economic expansion – if that is what we’re actually in. There is some question as to whether the post-financial-crisis era has not been so much a recovery as it has been an artificially induced turnaround built on the Federal Reserve’s bond buying binges (Quantitative Easing I, II and III) and the monster amounts of fiscal stimulus, including this current administration’s massive tax cuts.

Those artificial inducements, however, do not come without future pain and economic drag. The U.S. national debt now stands at $22 trillion while the Fed’s balance sheet still sits at $4 trillion.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s closely watched GDPNow forecast was just updated this morning. It is now forecasting GDP growth at a seasonally adjusted annual rate for the second quarter of 2019 at a tepid 1.3 percent. That would be a far cry from the 3.2 percent GDP growth of the first quarter and may signal that the economic bounce from the massive tax cuts has run out of steam while the burden on the next generation of Americans to deal with the national debt overhang continues to grow.