By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 28, 2016

Yesterday, the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR) released its 2015 Annual Report to Congress. OFR was created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to keep the Financial Stability Oversight Council informed on emerging threats to financial stability in the U.S.

Perhaps in an effort not to panic our sleeping Congress, or to further aggravate an already volatile stock market, the report said that “the United States financial system has continued to improve and threats to overall U.S. financial stability remain moderate.” From there, it went on to eviscerate that calm assessment with an endless stream of hair-raising concerns. One of those concerns is the interconnectedness of big Wall Street banks – a matter the OFR released a detailed paper on last February.

One fact you won’t find in the OFR report is that five of the biggest banks on Wall Street, which are also interconnected with one another, have seen their market capitalizations melt away like snow cones in July. Citigroup, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have cumulatively lost a total of $219.7 billion in market cap over the past seven months. All of the stocks are trading near their 12 month lows.

The declines in market cap stack up as follows: Citigroup, down $60.74 billion; Bank of America, down $53.3 billion; JPMorgan Chase, down $47.7 billion; Morgan Stanley, down $30.3 billion; and Goldman Sachs, a decline of $27.7 billion.

Not only are all of these Wall Street banks interconnected but they are also sitting with trillions of dollars of exposure to derivatives with the public in the dark as to whom the exposed counterparties are.

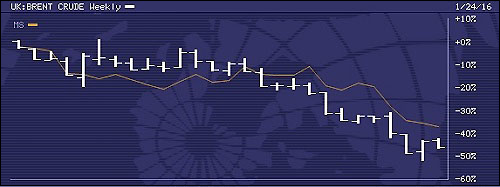

Another growing worry is exactly how exposed some of these banks are to the crash in oil prices. (See the chart of Morgan Stanley’s stock price above versus Brent crude oil. They have effectively been trading in a highly correlated manner.)

To listen to the fourth quarter earnings calls of the biggest banks, and the amounts that they have reserved for losses in the energy sector, one would think that this oil price collapse has been a minor blip rather than an unprecedented collapse. Since 2014, the price of crude oil has lost over two-thirds of its value and corporate credit downgrades have escalated.

In a January 14, 2016 report by Dow Jones, writer Michael Rapoport notes that “Even if banks do start building up reserves again, they are still near their lowest levels in recent years,” says Rapoport, adding that “Industrywide, banks’ bad-loan reserves were down to 1.37% of total loans and leases as of last Sept. 30, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., the lowest level since the end of 2007.”

Not only are the loan loss reserves stunningly low for what is happening in the real world but reserve levels from one bank to another make little sense. Reuters reports that JPMorgan Chase’s oil and gas loan portfolio amounted to $42 billion in the fourth quarter, but according to the transcript of its fourth quarter earnings call, its CFO, Marianne Lake said this about reserves:

“With obviously the biggest area of stress in wholesale being oil and gas, against which we built about $550 million in reserves this year including $124 million this quarter.”

That compares to Wells Fargo which has a far more modest $17 billion of oil and gas exposure but has taken $1.2 billion in reserves for potential losses.

Michael Rappoport hints in his article what might be going on at JPMorgan, writing:

“The buildup [in loan loss reserves] was also notable as it indicates the potential end of an era in which ‘releases’ of loan-loss reserves flowed into and offered a welcome boost to banks’ earnings, at a time when the banks often had difficulty generating profits from their operating businesses. Over the past six years, those releases have contributed nearly $25 billion to J.P. Morgan’s pretax income…”

The most interesting days are still ahead this year for the interconnected Wall Street banks which must undergo their stress tests at the Federal Reserve with depleted equity capital, rising corporate bankruptcies threatening their loan books, and growing calls from the campaign trail to break up these systemically risky institutions.