By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: October 21, 2014

In 30 years of observing Wall Street, we can’t remember a headline like the one that appeared yesterday at Reuters: “IBM to Pay GlobalFoundries $1.5 Billion to Take Chip Unit.” When one can’t even give a business away that includes thousands of patents, IBM engineers and two operating factories, times are tough. The market thought so also; by the closing bell yesterday, IBM’s stock was down $12.95, or 7 percent, to $169.10.

In 30 years of observing Wall Street, we can’t remember a headline like the one that appeared yesterday at Reuters: “IBM to Pay GlobalFoundries $1.5 Billion to Take Chip Unit.” When one can’t even give a business away that includes thousands of patents, IBM engineers and two operating factories, times are tough. The market thought so also; by the closing bell yesterday, IBM’s stock was down $12.95, or 7 percent, to $169.10.

The acquirer of the IBM semiconductor business, GlobalFoundries, is headquartered in Silicon Valley. Its parent is Advanced Technology Investment Company (ATIC), which is owned by the Abu Dhabi government’s investment arm, Mubadala Development Company. In May, ATIC announced it was changing its name to Mubadala Technology.

Abu Dhabi likely drove a very hard bargain with IBM in this deal because it has good reason to question promises made by American businessmen. As we reported in 2012, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund, ADIA, previously leveled a $4 billion fraud charge against Citigroup for taking it to the cleaners in a stock deal. That deal began with a hand shake from none other than former U.S. Treasury Secretary, Robert Rubin, who was serving as Citigroup’s interim Chairman at the time.

The two manufacturing facilities that come with the IBM deal are located in East Fishkill, New York and Essex Junction, Vermont. The $1.5 billion that IBM will pay GlobalFoundries will be spread over three years and is likely to help defray costs of facility upgrades. IBM has also agreed to a 10-year deal in which GlobalFoundries will be its exclusive provider of certain chipsets.

The trajectory of IBM’s stock price and its writeoffs are starting to bring back memories of the bad hand it dealt investors in the 90s. The stock is down from a price of more than $190 in September. Yesterday, in addition to the curious “pay-to-sell” deal, IBM also announced it was taking a $4.7 billion pre-tax charge in its third quarter and reported a 4 percent drop in revenues.

Over its more than a century of operations, IBM has repeatedly reinvented itself. That reinvention, however, has meant that investors have had long spells of dead money. The worst episode in IBM’s business history came in January 1993. The company announced it had lost $5 billion in 1992 and that it would slash its dividend to 54 cents from $1.21. Its stock had declined from $120 a share in 1990 to $48 and change at the time of the announcement.

Lou Gerstner was brought in from RJR Nabisco Holdings to replace longtime Chairman John Akers. The transition was not without pain. By the second quarter of 1993, IBM reported an additional $8 billion loss and announced it would be sacking tens of thousands of workers. The dividend was cut again, this time in half.

The 1990s reinvention of IBM has had a dramatic, negative impact on the long term total return of its stock and the wealth building capability of its long-term shareholders.

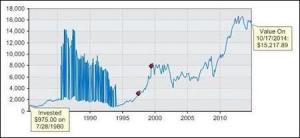

We decided to compare the performance of a cyclical computer company like IBM on a total return basis (share price appreciation plus dividend reinvested) from July 28, 1980 to October 17, 2014 versus the same period for Procter and Gamble, a household products company famous for iconic brands like Crest toothpaste and Ivory soap. We used the calculators available on the web sites of IBM and Procter and Gamble to make the calculations.

IBM delivered a total return of 1,460.62 percent over the period versus 3,104.82 percent for Procter and Gamble.