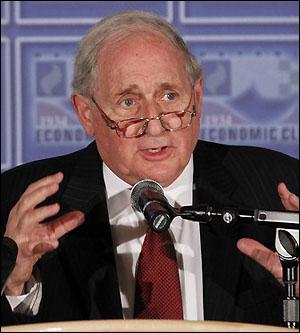

Senator Carl Levin opened today’s hearing on high frequency trading before the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations with this opening statement:

————-

Senator Carl Levin: Opening Remarks, June 17, 2014

Conflicts of Interest, Investor Loss of Confidence, and High Speed Trading

In U.S. Stock Markets

Most Americans’ image of the U.S. stock market is shaped by a single room: the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, where traders await a ceremonial bell to kick off the day’s activity, then trade shares worth millions on scraps of paper.

In reality, most shares are traded not on a floor in Manhattan, but in racks of computer servers in New Jersey. Trades happen not at the speed of a human scribbling on paper, but in the milliseconds it takes for an order to travel through fiber-optic cables. And increasingly, the money made on stock markets comes not from thoroughly assessing companies for their investment potential, but from exploiting infinitesimal advantages at unfathomable speeds, earning billions off price differences measured in pennies or less.

We are in the era of high-speed trading. I am troubled, as are many, by some of its hallmarks. It is an era of market instability, as we saw in the 2010 “flash crash,” which this subcommittee and the Senate Banking Committee explored in a joint hearing, and in several market disruptions since. It’s an era in which stock market players buy the right to locate their trading computers closer and closer to the computers of stock exchanges – conferring a miniscule speed advantage yielding massive profits. It’s an era in which millions of trade orders are placed, and then canceled, in a single second, raising the question of whether much of what we call the market is in fact an illusion.

Many, including this Senator, question whether the rise of high-speed trading is, overall, a good thing for markets or investors. But without question, this era has seen a rise of conflicts of interest. These conflicts will be my focus today. Other Senators may focus on this or other aspects of high-speed trading.

New technologies should not erase enduring values. Financial markets can’t survive on technology alone. They require a much older concept: trust. And trust is eroding. Conflicts of interest damage investors and markets – first, by depriving investors of the certainty that brokers are placing the interests of their clients first and foremost; and second, by feeding a growing belief that the markets are simply not fair.

In fact, polling shows that roughly two-thirds of Americans believe the stock market unfairly benefits some at the expense of others. This distrust may be a factor in the fact that just over half of Americans, according to a Gallup survey earlier this year, own stock or mutual funds, down from more than two-thirds of Americans who owned stock in 2002.That lack of faith – if allowed to fester and grow– will undermine a very important public purpose of stock markets: to efficiently raise capital so that businesses may grow, create new jobs and add to America’s prosperity.

In previous hearings and investigations, this subcommittee has shown that our financial markets have become plagued by conflicts of interest. We have uncovered investment banks willing to create securities based on junk assets, tout them to clients, and then bet against those same securities, making a fortune at the expense of their clients. We have seen credit rating agencies assign artificially high ratings to securities in order to keep or gain business. With that history in mind, those who argue that the conflicts we will explore at this hearing are manageable or acceptable have a mighty high burden of proof.

What seems to your average investor to be a simple stock-market trade is usually a complicated series of transactions involving multiple parties, complex technology, and an ever-increasing number of order types and payment arrangements. There are retail brokers, like the ones found in Main Street offices across the country and on TV advertisements. There are wholesale brokers who buy orders from retail brokers. And there are dozens of trading venues where shares are bought and sold. Most Americans know the New York Stock Exchange, but there are now 11 public exchanges, plus more than 40 alternative trading venues including “dark pools,” essentially private exchanges run by financial institutions.

As that complex structure has emerged, so have a number of conflicts of interest. This hearing will focus on two. The first conflict occurs when a retail broker chooses a wholesale broker to execute trades. The second occurs when a broker, acting on behalf of either a retail client or an institutional investor that manages pension funds and retirement accounts, chooses a trading venue, often a public exchange, to execute a trade. At both of those decision points, the party making the decision should only be influenced by the best interest of the investor – that’s what ethics demands, and it’s what the law requires.

But there’s another factor in play. At both decision points, the current structure gives brokers an incentive to place their own interests ahead of the interests of their clients. Here’s how.

The first conflict, as illustrated in this chart, occurs when retail brokers receive payments from wholesale brokers for their orders. This money, known as “payment for order flow,” can add up to untold millions, and almost every retail broker keeps these payments rather than passing them on to clients. The reasons wholesale brokers are willing to pay for order flow are complex, but one big one is that wholesale brokers can fill many of those orders out of their own inventory and profit from the trade – a practice known as “internalizing.”

The second conflict, shown on this chart, arises when a broker decides to use a public trading venue and then chooses which venue it will send orders to for execution. Under what is known as the “maker-taker” arrangement, there’s an incentive for the broker to choose the trading venue based on the broker’s financial interest, rather than a client’s.

“Maker-taker” can be complicated, but here’s a simplified explanation: When a broker makes an offer on an exchange to buy or sell a stock at a certain price, the broker is classified as a “maker,” and most exchanges will pay the broker a rebate when that offer to buy or sell is accepted. A broker who accepts a maker’s offer to buy or sell is called a “taker,” and will generally pay a fee to the trading venue. The important thing to remember is that brokers, by maximizing maker rebates and by avoiding taker fees, can add millions of dollars to their bottom line, giving them a powerful incentive to send the order to the trading venue that is in their best interest even if it’s not in their clients’ best interest.

It is significant that earlier this year, speculation that regulators were considering restrictions on payment for order flow sent shares of some brokerage firms significantly lower. Obviously, there is a lot of money at stake in preserving these conflicts of interest.

Even if firms disclose these payments, disclosure does not excuse them from their legal and ethical obligations to clients. Their legal obligation is to provide clients with what is known as “best execution.” Whether they are meeting that obligation is a subjective judgment. The outcome of this subjective judgment affects the way tens of millions of trades are executed.

Now, some who profit from these payments argue that seeking this revenue does not interfere with their obligation to seek best execution. However, one of our witnesses today, Professor Robert H. Battalio of the University of Notre Dame, has done research indicating that when given a choice, four leading retail brokers send their orders to the markets offering the biggest rebates at every opportunity. The research further suggests that exchanges offering the highest rebates do not, in fact, offer the best execution for clients. These brokers argue that they can pocket these rebates while still meeting their obligation to provide clients with best execution. So while they make a subjective judgment as to which trading venue provides best execution, on tens of millions of trades a year, that subjective judgment always just happens to also result in the biggest payment to brokers. I find it hard to believe that this is a coincidence.

Many market participants are worried about the conflicts of interest embedded in the current market structure. In addition to Professor Battalio, today’s first panel will include Bradley Katsuyama, the president and CEO of IEX and a prominent Wall Street advocate for market reform. Our second panel will include four witnesses. They are Thomas W. Farley of the New York Stock Exchange, whose corporate owners have described conflicts as having a “corrosive impact” on stock markets; Joseph P. Ratterman of BATS Global Markets, which operates exchanges that compete with NYSE and has a different view; Joseph P. Brennan of Vanguard Group, a major mutual fund company that has expressed concerns about these conflicts; and Steven Quirk of TD Ameritrade, a retail broker that derives significant revenue from payment for order flow from wholesale brokers and rebates from exchanges.

The duty of lawmakers and financial regulators is to look out for the interests of investors and the wider public. There is significant evidence that these conflicts can damage retirement savings, pension holdings and other investments on which Americans rely. And even Americans without a single share of stock or a mutual fund account have something at stake, because stock markets exist to foster investment, growth and job creation. Conflicts of interest jeopardize that vital function.

Americans don’t shy from innovation or technology; indeed we embrace them. But Americans are understandably suspicious when technology can be turned against them and their families’ financial interests. They are rightly concerned when technology and innovation are used to undermine basic, enduring principles such as trust and duty to a client. Our goal is to advance the protection of investors and our free markets by promoting those enduring values.

I want to thank Senator McCain and his staff for their close cooperation in this matter.