By Pam Martens: November 30, 2012

Congress and the President should rightfully be concerned about the dramatic decline in young, small businesses coming to market as initial public offerings. These are, hopefully, the innovative small businesses that will fuel the jobs of tomorrow. But as investments to stockholders, they lack a key element.

According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, small businesses:

• Represent 99.7 percent of all employer firms.

• Employ about half of all private sector employees.

• Pay 43 percent of total U.S. private payroll.

• Have generated 65 percent of net new jobs over the past 17 years.

• Create more than half of the nonfarm private GDP.

• Hire 43 percent of high tech workers (scientists, engineers, computer programmers, and others).

• Produce 16.5 times more patents per employee than large patenting firms.

Unfortunately for stock market investors, young companies typically do not pay any dividends, opting instead to plow earnings back into the company to foster innovation and growth. And that’s a problem if you’re a long-term investor.

Many Americans do not understand the concept of total return as it applies to stocks. If they did, there would be far less trading in and out of stocks. Total return is the combination of the price appreciation (or depreciation) derived from the movement in the share price of the stock combined with the dividend payment.

A full and enlightened understanding of that simple concept requires that one not only scour a company’s balance sheet and financial filings, but a review of its long-term history of raising its dividend is in order as well.

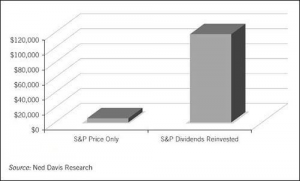

According to a study done by Ed Clissold for Ned Davis Research, dividends typically account for 45 percent of a stock’s total return, with the balance coming from price appreciation. But that figure does not capture the dramatic difference if compound interest is put to work.

According to Clissold, since December 31, 1929, the Standard and Poor’s 500 Index has produced an average of 4.92 percent in annual price appreciation through 2010 versus a 9.16 percent total return.

But what would have happened if investors had chosen to reinvest their dividends, rather than taking them in cash? From December 31, 1929 through 2010, $100 invested in the S&P 500 index would have grown to $4,989, but if dividends had been reinvested, the amount would be $117,774. That means that out of a total return of $117,774, just $4,989, or 4.2 percent, came from price appreciation, while 95.8 percent resulted from reinvesting dividends.

Compound interest and dividends are the two most basic principles of investing and also the two most frequently overlooked as critical components of a well thought out investment plan.

I also wonder how many seasoned investors will look at that $117,774 figure and say, something doesn’t look right. That amount seems small for holding the S&P for 80 years.

On Tuesday of this week, Matt Lauer of NBC’s The Today Show interviewed the legendary investor Warren Buffett who runs the conglomerate Berkshire Hathaway. Lauer had this to say in his introduction: “Back in 1966, if you spent about $220 to buy 10 shares of stock in Berkshire Hathaway it would be worth $1.3 million today.”

Comparing the Berkshire Hathaway example with the S&P example, that’s $220 invested for 46 years versus $100 invested for 80 — with a total return of $1.3 million versus $117,774. Is Buffett really that good or is something else at work here.

December 1929 was one of the worst times for investing in the history of investing, other than the beginning of September 1929 when the market peaked two months before the onset of the Great Crash that ushered in the Great Depression. Investors had to wait 25 years, until 1954, for the S&P to climb back and regain that lost ground.