By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 14, 2024 ~

It is now one of the unspoken but immutable dictates on Wall Street: with each new banking crisis, the Federal Reserve will quickly create an emergency bailout program and give it a three to four letter abbreviation so that it vanishes into an alphabet soup blur of Fed bailout programs that preceded it.

The latest iteration came in the spring of 2023 in response to a run on federally-insured banks that federal regulators had allowed to get in bed with crypto and/or had allowed to binge on uninsured deposits. The Fed quickly launched the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) on March 12, 2023.

BTFP joined the copious iterations from the Fed’s COVID-19 related bailouts and the Fed’s 2007-2010 bailouts with names like the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF), Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) and so on.

The one giant Fed bailout program that didn’t get an alphabet soup nickname was the Fed’s repo loan bailouts that occurred in the last quarter of 2019. By not naming the emergency lending program, perhaps the Fed was hoping its unsavory details would be forgotten. That program provided $19.87 trillion in term-adjusted revolving loans to the same Wall Street megabanks that the Fed had bailed out in the 2007-2010 crisis. (See Internal Charts Show Treasury Agency Assigned to Measure Risk in U.S. Markets Slept through the Repo Crisis of 2019 and the Fed’s $19.87 Trillion Bailout.)

Under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010, the Fed is required to keep the Senate Banking Committee and the House Financial Services Committee informed, on an ongoing basis, about its emergency lending programs. These, however, are bare bones reports. On Monday, for example, the Fed provided those Committees with an updated report on the Bank Term Funding Program. The names of the banks that were borrowing were not provided; neither current nor cumulative loan amounts outstanding for each respective bank was provided, and so forth. What was shared was that as of July 31, 2024, “The total outstanding amount of all advances under the BTFP was $102,065,995,000.”

You are likely asking yourself why an emergency Fed program to stop a bank run in the spring of 2023 still has $102 billion outstanding in the summer of the following year. The answer is that although the Fed stopped making new loans under the BTFP on March 11, 2024, the loans it had previously made were for as long as one-year terms. If, for example, the Fed initiated new loans on Friday, March 8, 2024, the BTFP could still have outstanding balances until March 8, 2025. That would mean that a Fed bailout facility created in March 2023 lasted for two years – defying the statutory language of the Federal Reserve Act which requires emergency lending by the Fed to be short term in nature.

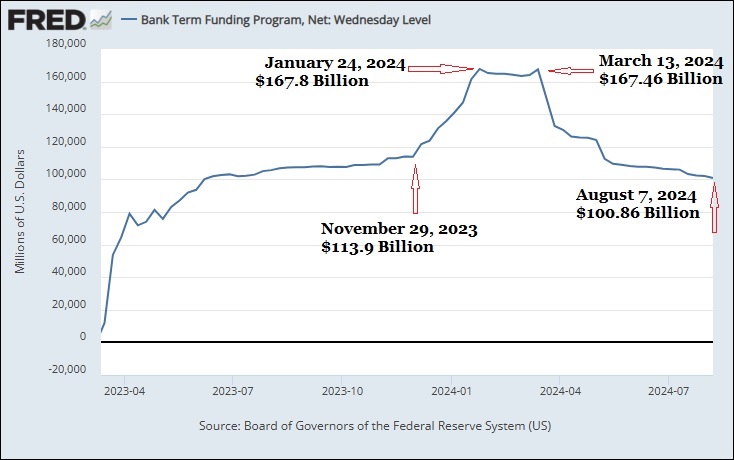

The chart above on the Bank Term Funding Program was created using data available at the St. Louis Fed. (Run your cursor over the chart line here.) It shows that by November 29, 2023, borrowing from the BTFP had leveled off to $113.9 billion – suggesting that the bank runs and panic had subsided. But then, between November 29, 2023 and January 24, 2024, borrowing from the BTFP emergency facility exploded by an additional $53.9 billion to $167.8 billion – a jump of 47 percent in less than two months.

What happened to expand the fear of bank runs into the fall of 2023? As the “Related Articles” below explain, August of 2023 saw multiple warnings and downgrades of banks from the credit rating agencies. Fitch’s downgrade of U.S. debt didn’t help either.

Then on November 17, Stanford’s Institute for Policy Research published a study titled: “Fragile: Why More US Banks Are at Risk of a Run.” The study made the following disturbing findings:

-

- Recent declines in bank asset values have significantly increased the vulnerability of the U.S. banking system to uninsured depositor runs.

- The actual market value of assets in the U.S. banking system is $2.2 trillion lower than the stated value of these assets.

- A substantial number of institutions are at risk of failing should there be a run on these banks by uninsured depositors.

As the chart above indicates further, 17 months after the Fed initiated its “emergency” BTFP lending facility, there is still an outstanding loan amount of $100.86 billion.

The Fed is perfectly able to make loans to individual depository banks under its Discount Window. That’s been one of its statutory roles since its creation – as a lender of last resort to depository banks. But beginning with the financial crisis of 2008, with no authorization from Congress, the Fed has decided willy nilly that it will expand its role to bailing out the trading houses on Wall Street on an ongoing basis, even going so far as to funnel tens of billions of dollars to their trading units in London in 2008, according to the government audit that was released in 2011.

If this is not the financial structure that you want to leave to your children and grandchildren, please call your U.S. Senators today and demand the restoration of the Glass-Steagall Act, which would permanently separate Wall Street’s casino trading houses from federally-insured banks.

Related Articles to Banking Crisis of 2023:

The Fitch Downgrade of U.S. Debt: What You Need to Know

S&P Downgrades Credit Ratings on Five Banks, Puts Three Others on Negative Outlook