By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 24, 2024 ~

Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, Testifying at Senate Banking Hearing on the Bank’s London Whale Scandal on June 13, 2012

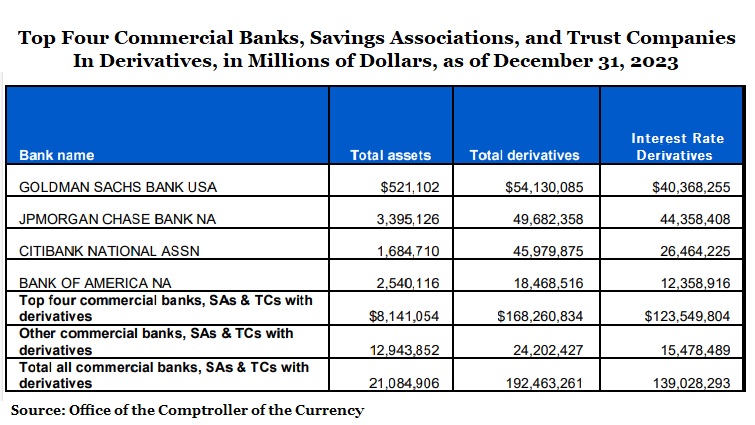

Since the financial crash of 2008 and the Fed’s multi-trillion dollar bank bailouts that followed, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has been waving a giant red flag every quarter in its “Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities” reports. For sixteen years the OCC has been reporting that just four megabanks are responsible for more than 80 percent of the trillions of dollars in bank derivatives.

As the chart above shows, as of December 31, 2023, Goldman Sachs Bank USA, JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A., Citigroup’s Citibank and Bank of America held a staggering total of $168.26 trillion in derivatives out of a total of $192.46 trillion at all U.S. banks, savings associations and trust companies. That’s four banks holding 87 percent of all derivatives at all 4,587 federally-insured institutions in the U.S. that existed as of December 31, 2023.

Now, it would appear, some market-savvy bank examiner embedded in one of those megabanks has had an epiphany and decided to ask the question: “How is it possible that all four of these megabanks with trillions of dollars in derivatives happened to be on the correct sides of these trades during the fastest and steepest interest rate increases in 40 years?” Multiple bank counterparties to these trades should be reporting massive losses and yet all we hear are crickets.

This puzzle becomes all the more urgent if you take a closer look at the above chart and notice that $40.368 trillion of Goldman Sachs Bank USA’s $54.13 trillion in derivatives are interest rate derivatives, or 75 percent. JPMorgan Chase’s interest rate derivatives represent 89 percent of its total of $49.68 trillion in derivatives.

The OCC report for the quarter ending December 31, 2023 also shows that $20.8 trillion of these interest rate derivative contracts at these four megabanks have maturities in excess of five years – a very long time to climb out on a limb on interest rate decisions by the Fed.

On Friday, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Federal Reserve Board jointly released their findings on the resolution or wind-down plans in a potential bankruptcy of the eight megabanks in the U.S. The plans are also known as “living wills.”

It came as no surprise to us that the four largest U.S. derivative banks — JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup’s Citibank, Bank of America and Goldman Sachs — were faulted on shortcomings in how they planned to wind down their derivatives. The surprise was that the Fed – which has a gold-plated revolving door to these banks – would acknowledge the derivatives problem after years of ignoring it.

The Fed and FDIC wrote the following in their letter to Jamie Dimon, the Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, which regulators already acknowledge is the riskiest bank in the U.S. (but nonetheless allowed it to get even bigger and riskier in May of last year by rubber-stamping its purchase of the collapsed First Republic Bank):

“The Agencies found the Covered Company’s 2023 Plan to have a shortcoming related to the implementation of its derivatives unwind strategy. An assessment of the Covered Company’s capability to unwind its derivatives portfolio under conditions that differed from those specified in the 2023 Plan revealed some weaknesses in the refresh of and approach to compiling financial results. This, in turn, raises questions about the firm’s ability to implement this aspect of its preferred strategy in an actual resolution event. Specifically, in response to a capabilities test initiated by the Agencies, the response from the firm showed that the firm is unable to update certain economic conditions in its entity-level-resource-needs calculation of resolution capital execution need (RCEN) and resolution liquidity execution need (RLEN) associated with unwinding its derivatives portfolio in a timely manner. Furthermore, the firm did not accurately incorporate funding assumptions as specified by the Amended and Restated Support Agreement dated June 5, 2019, as amended, in the current resolution metrics production process. To remediate this shortcoming, the Covered Company’s 2025 Plan should demonstrate, including through reporting in the 2025 Plan on internal validation and testing conducted by the Covered Company, that the Covered Company has developed the ability to quantify each material legal entity’s RLEN and RCEN for changes in macro/financial market conditions, calculate recapitalization needs for a macro scenario change in a timely way, and provide for downstream liquidity and capital funding needs according to the terms of the Amended and Restated Support Agreement. The Covered Company should develop and submit to the Agencies by September 1, 2024, a description of the key actions needed to remediate this shortcoming and a timeline illustrating the date of their expected completion.”

Adding to the hubris, this is now the second time in eight years that federal regulators have told Dimon to get his act together in dealing with derivatives if the bank has to wind-down operations. In a letter dated April 12, 2016, the Fed and the FDIC faulted the bank on its trading and derivative plans. The letter was apparently so frightening that numerous segments were redacted by the two federal regulators by blacking out the text.

The Fed and FDIC appear like indulgent parents of an out-of-control teen when it comes, particularly, to JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon and derivatives. This is, after all, the bank that triggered an in-depth investigation by the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 2012-2013 for gambling in derivatives in London using deposits from its federally-insured bank and losing $6.2 billion of its depositors’ money. This became infamously known as the bank’s “London Whale” scandal.

Dimon was hauled before the Senate Banking Committee on June 13, 2012 to answer questions about the London Whale scandal. Instead of falling on his sword or taking a humble approach to the bank’s abysmal conduct, he spoke as if he were testifying as an expert witness for the banking industry instead of the man sitting at the center of the scandal. Dimon said this in answer to a question from Senator Jerry Moran:

“We have to get rid of anything that looks like too-big-to-fail. We have to allow our biggest institutions to fail. It is part of the health of the system, and we should not prop them up. We have to allow them to fail.

“And I would go one step further. You want to be sure that they can fail and not damage the American economy and the American public. So a big bank, you want to be in a position where a big bank can be allowed to fail.

“I wouldn’t call it ‘resolution.’ I think that’s the wrong name. I think we should call it ‘bankruptcy.’ Personally, I call it ‘bankruptcy for big dumb banks.’ I think when you have bankruptcy, I’d have clawbacks. I’d fire the management. I’d fire the Board. I’d wipe out the equity and the unsecured [debt holders] should only recover whatever they recover like in a normal bankruptcy.”

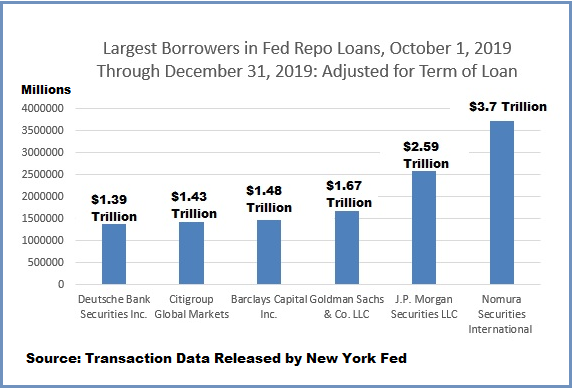

Just six years after Dimon’s “bankruptcy for big dumb banks” speech to the Senate Banking Committee, his bank began secretly taking trillions of dollars in emergency bailout loans from the Fed for a financial crisis that has yet to be explained. (See chart below.)

The four megabanks that were not faulted last Friday by the Fed or FDIC for their wind-down plans were Wells Fargo, Bank of New York Mellon, State Street and Morgan Stanley. (Morgan Stanley’s bank holding company has a monster amount of derivatives according to the OCC, however, its federally-insured banking footprint pales in comparison to JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Citigroup’s Citibank.)