By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 24, 2024 ~

To read main stream media headlines, one would think that the Federal Reserve Inspector General’s Office has exonerated former Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan of any legal action for trading like a hedge fund kingpin while he was privy to insider information at the Fed.

In fact, all that the Inspector General’s report has cleared Kaplan of is this: “we did not find that his trading activities violated laws, rules, regulations, or policies related to trading activities as investigated by our office.”

What the Inspector General did not investigate is everything that a real insider trading investigation would have encompassed. It did not investigate if Kaplan was shorting the market with his $1 million plus trades in and out of S&P futures contracts during a declared National Emergency over the COVID pandemic while making market diving predictions on TV; it did not investigate how big ticket trading by a Fed insider got past the compliance department of the brokerage firm Kaplan was using to transact his trades, which may have been the notorious Goldman Sachs; it did not investigate if that brokerage firm was cloning Kaplan’s trades (because he was a Fed insider) for its own profit and benefit.

In short, the Fed Inspector General didn’t do anything that a real investigator at the Securities and Exchange Commission would have done and its report is silent on whether it made a referral to the SEC or the Justice Department in this matter. What the Inspector General did do was to sit on this investigation for more than two years and then deliver a report so hopelessly inept that it provided the long missing dates that Kaplan traded but not the essential information as to whether those trades were purchases or sales. (Kaplan had been allowed by the Fed to evade the required reporting of specific dates for each sale and each purchase of a security for the entire five years he filed his financial disclosure forms at the Dallas Fed. See Kaplan’s financial disclosure forms from 2015 through 2020 here.)

As a former CPA and Goldman Sachs veteran, Kaplan knew or should have known that his financial disclosure forms were breaking Fed rules as well as common sense rules for financial disclosure of trading activities.

In 2020, during the worst health crisis in more than a hundred years in the United States, Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan, then a voting member of the FOMC, was frequently throwing trading fuel on a deepening economic meltdown in his print media interviews. Also in 2020, Kaplan was trading in and out of S&P 500 futures, according to his own financial disclosure forms. (Trading in S&P 500 futures is a market-timing device used by hedge funds and day traders. No individual with market-moving information at the Federal Reserve should ever be allowed to use such a device.)

Kaplan gave a total of 68 interviews with the press in 2020, a stunning number and a smoking gun for a man also trading S&P 500 futures.

Twice in the span of six days in May of 2020, Kaplan predicted that unemployment was going to surge to 20 percent. That’s a very bold and apocalyptic call that would have benefited short sellers. According to the Congressional Research Service, the maximum unemployment rate in 2020 topped out at 14.8 percent in April.

Kaplan first made the 20 percent unemployment prediction on Fox Business with Maria Bartiromo, the cable TV show, on May 1, 2020. When the interview started, around 8:34 a.m. ET, Dow futures were down 450 points. By the time Kaplan finished speaking, Dow futures had dropped another 10 points. The Dow closed the day down 622 points. You can watch the program here. In addition to the 20 percent unemployment prediction, Kaplan also described the economic outlook in the interview as an “historic contraction,” “very severe,” and noted that the consumer (which represents two-thirds of GDP growth in the U.S.) had “suffered a body blow.”

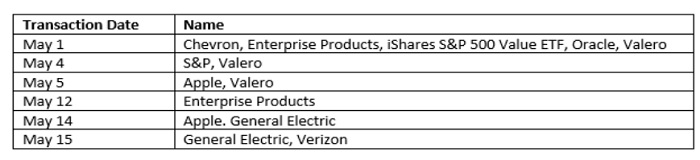

Now we learn from the Fed Inspector General’s report that on the very day Kaplan was providing fuel for short sellers on TV, he was also actively trading himself on May 1, 2020. Below is a screen shot from the Inspector General’s report for the month of May 2020, showing Kaplan’s trading. According to his previously filed financial disclosure forms, each trade was in excess of $1 million.

Also note the absurdity of an Inspector General taking two years to conduct this investigation, stating that it had access to Kaplan’s brokerage statements, and then failing to indicate on the above chart whether these trades were purchases or sales. We reached out to the Inspector General’s office yesterday, asking for this long overdue information. Their response was: “Thanks for your inquiry but we decline to comment.”

Because the Fed was engaging in unprecedented bailout operations in 2020 to stem the economic damage from COVID, in addition to its regular blackout trading bans around FOMC meetings, the Fed imposed an additional blackout period from March 23, 2020 through April 30, 2020. The Fed sent advisories to this effect to each regional Federal Reserve Bank, including the Dallas Fed.

On the very first day after this blackout period ended, May 1, 2020, Kaplan was back to trading like a hedge fund kingpin while simultaneously using his stature as a Fed Bank President to make outrageous negative predictions on a TV show watched by traders.

Kaplan could have made money by shorting the market ahead of his negative pronouncements or he could have bought low after making those pronouncements.

Neither the Dallas Fed nor the Inspector General will say if Kaplan engaged in shorting the market during a national health crisis. (Shorting means to place a bearish bet that the market or a security will fall in value.) Goldman Sachs did not respond to multiple inquiries, one as recently as yesterday, as to whether it was the brokerage firm conducting Kaplan’s trades. There is a strong suggestion that Goldman Sachs is where Kaplan was trading because he was using a Goldman Sachs, “GS,” money market fund to hold idle cash not deployed for trading.

Kaplan was also trading in and out of oil stocks in 2020, including shares of Chevron, Marathon Petroleum, Occidental Petroleum and Valero Energy. According to Kaplan’s financial disclosure form for 2020, he made “multiple” trades in each of these oil stocks in sums of “over $1 million.”

On May 28, 2020, Kaplan gave an interview to Reuters news wire which generated a headline that he was predicting “a global oil glut lasting well into 2021.” He also made the bearish comment in the interview that many smaller firms and those with lots of debt may not survive.

West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the U.S. domestic crude oil that trades, had collapsed from a price of $60 a barrel at the beginning of 2020 to a range of $30 at the time of the Reuters’ interview with Kaplan. Calling for a “global oil glut lasting well into 2021” was not a bullish call for the oil fields in Texas. WTI actually bounced back to its $60 handle in early April of 2021.

Despite the Inspector General’s finding that Kaplan violated no Fed rules, the type of trading done by Kaplan appears to be expressly prohibited by the Code of Conduct of the Dallas Fed. Appendix A on “Disqualifying Interests” of the Code of Conduct reads as follows:

“De minimis exemption for a matter of general applicability. An employee may participate in a particular matter of general applicability, such as rulemaking, where the disqualifying financial interest arises from ownership by the employee, his or her spouse or minor children of securities issued by one or more entities affected by the matter, if:

“(1) the securities are publicly traded, or are municipal securities, the market value of which does not exceed; (a) $25,000 in any one such entity; and (b) $50,000 in all affected entities;

“or (2) the securities are long-term federal government securities, the market value of which does not exceed $50,000.”

There was certainly nothing de minimis about Kaplan’s trading. In addition to his “multiple” trades in and out of S&P 500 futures, he lists on his financial disclosure form for 2020 “multiple” purchases and sales of greater than $1 million per transaction in 11 individual stocks. Three of those were interest-rate sensitive Big Tech stocks (Amazon, Apple and Facebook) that rose between 75 percent to 90 percent from their March 2020 lows, in no small part because of the interest rate cuts and other interventions by the Federal Reserve in 2020.

The Federal Reserve had very specific rules against Kaplan’s style of speculative trading for decades, but those rules somehow managed to vanish into thin air.

On August 12, 1977, the Comptroller General of the U.S., Elmer Staats, filed a report with Congress in which he warned that the Federal Reserve’s financial disclosure system was woefully lacking. Staats specifically called out the Fed’s failure to define with specificity what constituted prohibited “speculative dealings” for its employees.

Staats notes in the report:

“Federal Reserve regulations on standards of conduct are issued to each Board employee. Specific Board prohibitions on financial interest state that an employee may not: Have a direct or indirect financial interest that conflicts substantially, or appears to conflict substantially, with his duties and responsibilities; Engage in speculative dealings (as distinguished from investments) in securities, commodities, real estate, exchange, or otherwise. Frequency of trading, the use of credit, and particularly transactions to take advantage of short-term price fluctuations would be significant indications that dealings were speculative.”

That last sentence in the above paragraph is the quintessential definition of trading in S&P 500 futures.

This Federal Reserve rule prohibiting speculative dealings was still in force at the Federal Reserve on December 19, 1995 because the following reference appears in the Federal Register for that date:

“A provision of the Board’s current ethics rules prohibits Board employees from engaging in speculative dealings. See 12 CFR 264.735–6(d)(iii).”

When we looked in 2021 at the then current Federal Reserve Board of Governors’ ethics rules and those that had been published for each of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks, we found zero references to “speculative dealings.”

What we did find, however, was the following sentence in 11 of the 12 regional Federal Reserve banks’ codes of conduct: (The Atlanta Fed words the statement differently but with the same overall meaning.)

“Each employee has a responsibility to the Bank and to the System to avoid conduct which places private gain above his or her duties to the Bank, which gives rise to an actual or apparent conflict of interest, or which might result in a question being raised regarding the independence of the employee’s judgment or the employee’s ability to perform the duties of his or her position satisfactorily.”

Clearly, Kaplan violated the above rule when he started trading in and out of S&P 500 futures.

There are three typical reasons for an individual to trade in speculative, short-term S&P 500 futures: (1) the individual thinks he or she can time the market’s moves; (2) the individual wants to trade before or after stock exchange hours; (3) the individual wants to make highly leveraged bets on the market’s direction, going both long and short.

One of the most striking, and disturbing, facets to Kaplan’s trading is how many safeguards that are built into the system, both at the Dallas Fed and at the brokerage firm that placed his trades, failed to sound the alarms that should have gone off regarding this unprecedented speculative trading activity by a man regularly having access to non-public, market moving information at the Fed.

The Dallas Fed has its own Board of Directors, with an Audit Committee. According to the Audit Committee’s charter, it is empowered to do the following, among many other things:

“Obtain updates from the Bank’s General Counsel on any legal matters or code of conduct or ethical concerns that could have a significant impact on the financial statements or compliance matters.

“Authorize special investigations and reviews, and engage independent counsel and other advisors as it determines necessary to carry out its duties and responsibilities.”

Sharon Sweeney was the General Counsel at the Dallas Fed during Kaplan’s trading spree and had been with the Dallas Fed for 35 years. According to the Internet Archives’ Wayback Machine, Sweeney had served in the dual role as General Counsel and Ethics Officer since at least 2017. (Sweeney has since left the Dallas Fed.)

It is the Ethics Officer’s signature that appears directly under Kaplan’s on each of his financial disclosure forms for 2015 through 2020, along with the following statement for the Ethics Officer: “I CERTIFY that I have reviewed the information contained in this report.”

It was probably not a benefit to good governance at the Dallas Fed that Kaplan had the power to fire Sweeney “at his pleasure.” The Dallas Fed Board of Directors’ bylaws indicate this: “Subject to applicable law and rules of the Board of Governors, the President, and any officer(s) authorized by the President, has the power to suspend or dismiss at pleasure any employee or officer of the Bank, other than the First Vice President.”

Then there is the External Auditor of the Dallas Fed. The Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington D.C. annually selects the external auditor for the regional Fed banks. From 2015 through 2020, the Federal Reserve Board had annually chosen the same auditor, KPMG, to perform the external audit for all 12 of the regional Fed Banks. KPMG is one of the Big Four Accounting firms. How it missed Kaplan’s aggressive, speculative trading is one more black eye for the firm.

KMPG is also the accounting firm that audited the three banks that became the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history in the spring of 2023: Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, which failed in March 2023; and First Republic Bank, which failed on May 1, 2023.

Every licensed broker that would have been placing Kaplan’s “over $1 million” trades is required under regulatory rules to “Know Your Customer.” The rule states that “Every member shall use reasonable diligence, in regard to the opening and maintenance of every account, to know (and retain) the essential facts concerning every customer and concerning the authority of each person acting on behalf of such customer.”

In Kaplan’s case, knowing your customer should have meant frantically calling your compliance department when an officer of the U.S. central bank, who sits on some of the most sensitive, non-public market intelligence in the world, instructs you to make “over $1 million” trades, multiple times, in S&P 500 futures contracts. The S&P 500 futures trade request by Kaplan should have convened an immediate, all-hands-on-deck meeting of the entire compliance department of the brokerage firm. Instead, the trading continued unimpeded for more than five years, according to Kaplan’s financial disclosure forms.

Every brokerage firm has a compliance department that monitors the trades being placed by their brokers. The compliance department has access to the personal data for each client that indicates who their employer is, along with significant other personal information. Clients whose jobs involve having access to confidential market information, like an investment banker or a central banker, would have their trades closely monitored in a properly functioning compliance department.

This compliance department was clearly not functioning and the American people need to know why.

In addition to the Know Your Customer Rule, the U.S. Treasury Department’s FinCEN (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network) has its own Customer Due Diligence Rule (CDD Rule). One of the requirements under the rule is that financial institutions “use a specific method or categorization to risk rate customers; or automatically categorize as ‘high risk’ products and customer types that are identified in government publications as having characteristics that could potentially expose the institution to risks.”

Kaplan previously worked for 22 years at one of the most sophisticated trading firms on the globe, Goldman Sachs. He rose to the rank of Vice Chairman at Goldman Sachs and had “global responsibility for the firm’s Investment Banking and Investment Management Divisions,” according to his official bio at the Dallas Fed.

There is no question that a former Vice Chairman of Goldman Sachs who had been a former CPA for Peat Marwick Mitchell understood that trading in and out of S&P 500 futures in “over $1 million” transactions when the President of the United States has declared a National Emergency and Kaplan was sitting on non-public information from the central bank of the United States was scandalous, if not illegal, behavior.

Another safeguard that failed was the vetting of Kaplan for the position of Dallas Fed President by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors in Washington D.C. While the Class B and C Directors of the Dallas Fed Board appoint their President, he is also subject to the approval of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, who should have done extensive due diligence on Kaplan because of his 22 years at Goldman Sachs, including the immediate years leading up to the greatest financial crash since the Great Depression – a crisis in which Goldman Sachs played a toxic role.

On April 11, 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a notice indicating that Goldman Sachs was fined “more than $5 billion” by various regulators. A statement in the notice from Acting Associate Attorney General Stuart Delery said that “This resolution holds Goldman Sachs accountable for its serious misconduct in falsely assuring investors that securities it sold were backed by sound mortgages, when it knew that they were full of mortgages that were likely to fail.”

An in-depth investigation of Goldman Sach’s role in the subprime crisis that crashed Wall Street in 2008 was released by Greg Gordon of McClatchy Newspapers in 2015. Gordon writes:

“From 2001 to 2007, Goldman hawked at least $135 billion in bonds keyed to risky home loans, according to analyses by McClatchy and the industry newsletter Inside Mortgage Finance…

“It also was the lead firm in marketing about $83 billion in complex securities, many of them backed by subprime mortgages, via the Caymans and other offshore sites, according to an analysis of unpublished industry data by Gary Kopff, a securitization expert.”

From 2001 through most of 2005, the majority of the period referenced above, Kaplan was a key member of management of Goldman Sachs. That should have been an immediate disqualifier for moving up to the position of President of a Federal Reserve Bank.

At the time of Kaplan’s appointment to the Dallas Fed in 2015, an activist group raised red flags. Ady Barkan, Director of the Center for Popular Democracy’s Fed Up campaign, released this statement in 2015 on the day the Dallas Fed announced it had chosen Kapan as its next President:

“…the Dallas Fed selected a veteran of Goldman Sachs who is currently a director at the headhunting firm that was hired to fill this position. Neither the process nor the result serves the public interest. The Fed should do much better…

“The revolving door in the Federal Reserve continues to spin, with Richard Fisher leaving the Dallas Fed to work at Barclay’s Bank (which pleaded guilty to serious financial crimes), and a Goldman Sachs banker coming in.”

The Federal Reserve Board of Governors not only signed off on Kaplan’s appointment to the Dallas Fed once, but they reconfirmed his appointment in 2021 to serve for another five years as President of the Dallas Fed. On January 21, 2021 the Fed released a press statement indicating that after “a rigorous process to inform their reappointment decisions” it was reappointing all 12 regional Fed Bank presidents “to serve a new five-year term beginning March 1, 2021.”

This “rigorous” process apparently did not think trading like a hedge fund kingpin was a disqualifier for Kaplan.

It’s time for the SEC and/or the U.S. Department of Justice to speak out on this national disgrace and tell the American people if they have an ongoing investigation.