By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: February 10, 2023 ~

Credit Suisse continued its long death spiral yesterday, losing 15.64 percent of its market value in one trading session to close at $3.02 on the New York Stock Exchange. The trading action came on the heels of an earnings report that was excruciatingly bad – even for Credit Suisse.

Credit Suisse continued its long death spiral yesterday, losing 15.64 percent of its market value in one trading session to close at $3.02 on the New York Stock Exchange. The trading action came on the heels of an earnings report that was excruciatingly bad – even for Credit Suisse.

The Global Systemically Important Bank (G-SIB), which means it’s interconnected to other G-SIBs that could bring down the global financial system, reported yesterday that its clients had yanked over $100 billion in just the fourth quarter — which was more than eight times the outflow in the third quarter. Its pre-tax loss for the quarter was $1.51 billion, marking its fifth consecutive earnings loss.

Credit Suisse is Switzerland’s second largest bank, after UBS, but its troubled history looks more like that of a bank in a banana republic. On March 26, 2021, the family office hedge fund, Archegos Capital Management, defaulted on margin calls to its prime brokers and went belly up, leaving major investment banks with more than $10 billion in losses. Credit Suisse took the lion’s share of those losses, acknowledging a loss of more than $5.5 billion. (To fully appreciate the wild risks that mega banks were taking with Archegos, see our report: Archegos: Wall Street Was Effectively Giving 85 Percent Margin Loans on Concentrated Stock Positions – Thwarting the Fed’s Reg T and Its Own Margin Rules.)

The Board of Credit Suisse decided to hire the Big Law firm, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, to conduct an internal investigation of the Archegos fiasco. Paul Weiss issued a 165-page report in July of 2021, detailing its version of what had happened. Paul Weiss, reliably, found that no fraud had occurred — just zombie risk management at a Global Systemically Important Bank. (Some shareholders might have been more comforted with a finding of fraud.)

Paul Weiss investigators portrayed the zombie risk managers at Credit Suisse as follows:

“The Archegos-related losses sustained by CS [Credit Suisse] are the result of a fundamental failure of management and controls in CS’s Investment Bank and, specifically, in its Prime Services business. The business was focused on maximizing short-term profits and failed to rein in and, indeed, enabled Archegos’s voracious risk-taking. There were numerous warning signals — including large, persistent limit breaches — indicating that Archegos’s concentrated, volatile, and severely under-margined swap positions posed potentially catastrophic risk to CS. Yet the business, from the in-business risk managers to the Global Head of Equities, as well as the risk function, failed to heed these signs, despite evidence that some individuals did raise concerns appropriately.”

Credit Suisse’s reputation has taken more hits from its involvement in the Greensill Capital scandal and the infamous spy-gate scandal in 2019 where the bank spied on and followed various employees. (You can’t make this stuff up.)

Nervousness about Credit Suisse reached a pivotal moment in the fall of last year. On November 30, its 5-year Credit Default Swaps (CDS) blew out to 446 basis points. That was up from 55 basis points in January of 2022 and more than five times where CDS on its peer Swiss bank, UBS, were trading. The price of a Credit Default Swap reflects the cost to traders, or investors with exposure, to insuring themselves against a debt default by the bank.

The big move in CDS on Credit Suisse had started in early October of 2022. On October 3, 2022, Dennis Kelleher, President of the nonprofit watchdog, Better Markets, summed up the situation and its potential impact on American taxpayers as follows:

“As the financial condition of Credit Suisse continues to deteriorate, raising questions of whether it will collapse, the world and U.S. taxpayers should be deeply worried as multiple, simultaneous shocks shake the foundations of economies worldwide. Credit Suisse is a global, systemically significant, too-big-to-fail bank that operates in the U.S. and is deeply interconnected throughout the global financial system. Its failure would have widespread and largely unknown repercussions from the inconvenient to the possibly catastrophic.

“That is due, in part, to the failure of the Federal Reserve to properly regulate the activities of foreign banks that have U.S.-based operations. The U.S. has a largely ineffective regulatory framework with gaping loopholes that fail to include some of even the most basic safety and soundness requirements, which incentivizes regulatory arbitrage. As a result, the U.S. financial system and economy are needlessly threatened.

“An effective and appropriate regulatory framework for large foreign banks that covers all of their U.S.-based affiliates should have been established when the Fed set up so-called U.S.-based intermediate holding companies (‘IHCs’) that they regulate. Instead, U.S.-based branches of foreign banks (which are not consolidated within the IHC) face significantly weaker standards than the IHC, remarkably including no specific capital requirements in the U.S. Furthermore, the branches have significantly weaker liquidity requirements. This has resulted in many foreign banks – including in particular Credit Suisse – engaging in regulatory arbitrage by shifting large amounts of assets from their IHCs to their branches, entities that are entirely reliant on the resources of their foreign-based parent companies. The 2008 financial collapse proved that these resources are not available in periods of stress, which is why the U.S. bailed out so many foreign banks operating in the U.S. The Fed should have stopped that long ago.

“As is well-known, risks in the global financial system that materialize elsewhere easily end up becoming risks here in the U.S. and threaten our financial system and economy. Those risks are amplified by the unprecedented fiscal and monetary policies attempting to address the many unexpected shocks from the pandemic and war. The Fed must see Credit Suisse as a warning sign and improve the regulatory framework for large foreign banks and all banks to ensure that the American financial system and economy are properly protected.”

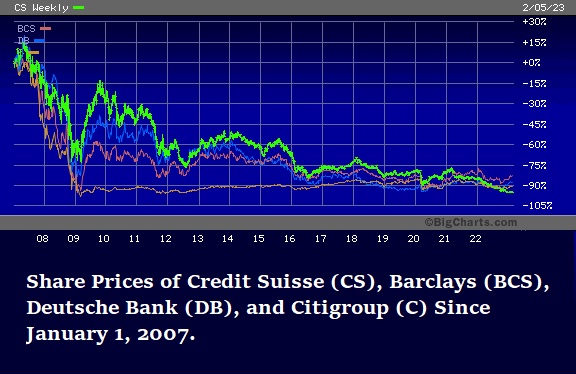

Unfortunately, Credit Suisse is far from alone. As the chart above indicates, Credit Suisse, Barclays (U.K.), Deutsche Bank (Germany) and Citigroup (U.S.) have lost the bulk of their market value since January 1, 2007 – or prior to the financial crisis of 2008. And all of these banks are also G-SIBs and interconnected to one another through derivatives, loan relationships and the like.

The bottom line is that Congress, the Fed and other federal regulators have seriously failed in their obligation to ensure that there is not another replay of the Wall Street mega bank meltdown of 2008 – which brought on the worst economic collapse since the Great Depression.