By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 13, 2025 ~

Most retirees have a significant part of their net worth in their homes. Until recent years, it was reasonable to assume that if you kept your home in good repair, your home would be standing for multiple generations.

But as we learned from the impact of Hurricane Helene’s catastrophic rain events in North Carolina in September of last year, and from the ongoing devastating fires around Los Angeles today, a wood frame (a/k/a “stick-built”) home can be turned into a pile of smoldering rubble with little time to escape in this era of climate-change hellscapes.

The main problem for Western North Carolina in September wasn’t wind speed – but over two feet of rainfall in some areas over three days that transformed scenic rivers into raging beasts that leveled homes, entire towns, roads, bridges, water mains and left some electric utility substations submerged under water according to Duke Energy, which supplies electricity to much of the area.

Photo Posted on Twitter (X) of What’s Left of Homes in Chimney Rock, North Carolina in September 2024

Meteorologist Ryan Maue posted a graph on his Twitter (X) page on September 29, indicating that between Tuesday, September 24, and Sunday, September 29, there had been 20 trillion gallons of rainfall across Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee.

The science-fiction like scenes of devastation on both U.S. coasts over the past year, as temperatures continue to set historic records, has sparked a rethinking of how homes are built in the United States, with concrete gaining long overdue attention. While concrete block homes are common in some southern states, wood remains the preferred material for builders in most northern and central states.

According to the National Association of Home Builders, 90 percent of homes built in 2019 in the U.S. were wood-framed. (This would appear to be ignoring the scientific evidence that trees are important to carbon capture and to slow climate change.)

As far back as three decades ago, the Los Angeles Times published an article about a concrete home in Malibu, owned by Mary Ellen Strote, that had survived the devastating Calabasas/Malibu firestorm of 1993, while wood framed homes burned to the ground.

In 2019, the Wall Street Journal published an article describing a concrete home owned by Phillip Vogt that had survived the catastrophic Woolsey firestorm in California in November 2018.

And just three days ago the Daily Mail published photos and an article about the three-story stucco and stone home of David Steiner, which can be seen standing among the charred rubble of wood framed homes on the beach in Malibu from the ongoing Palisades fire.

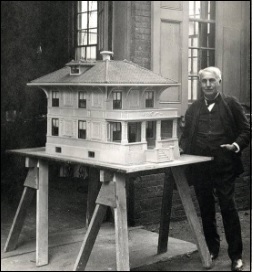

Thomas Edison is credited with designing and building the first poured-concrete homes in the U.S. in New Jersey in the early 1900s. One of Edison’s poured-concrete homes remains standing today at 303 N. Mountain Avenue in Montclair, New Jersey. It was built in 1912. A local historical organization describes the home as follows:

“This house is on the New Jersey Register of Historic Places as an example of a poured-concrete house designed by Thomas Edison to provide mass-produced affordable housing. Montclair resident Frank D. Lambie was instrumental in construction by designing and building the molds through his Lambie Concrete House Corporation and New York Steel Form Company. A 1910 version of this construction technique is at 420 Valley Road in Montclair.”

Realtor.com estimates that the 112-year old home’s current market value is $1.13 million.

Unfortunately, according to Green Building & Design Magazine, because concrete and cement are used widely to build bridges, tunnels, and dams across the U.S., and cement-block homes in southern hurricane-prone states, they also account for approximately 7 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions.

The Global Cement and Concrete Association (GCCA) says it is well on its way to a decarbonization future, citing groundbreaking efforts by its members:

“For example, Cemex has been working with Switzerland-based Synhelion to produce clinker [the binder in cement] using solar energy. Votorantim Cimentos in Brazil is using discarded pits from the native acai fruit to turn into biomass as an energy source. And Heidelberg Materials is building the world’s first large-scale carbon capture plant at its site in Brevik, Norway. It aims to start capturing emissions from production by the end of next year with the capacity to absorb about 400,000 tons a year, when fully operational. The GCCA Roadmap anticipates 10 carbon capture plants being operational at commercial scale by 2030.”