By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 22, 2024 ~

The Washington Post Editorial Board appears to have sipped the same kool aid as Bloomberg News.

The Washington Post Editorial Board appears to have sipped the same kool aid as Bloomberg News.

As we’ve frequently reported in the past, Bloomberg News has spent the better part of the last decade attempting to brainwash the public into believing that the head of JPMorgan Chase, Jamie Dimon, is a respected statesman of Wall Street. (See here, here, and here.) In reality, JPMorgan Chase has admitted to an unprecedented five criminal felony counts with Dimon at the helm and paid fines in the tens of billions of dollars for an additional crime wave that rivals an organized crime family.

Billionaire Michael Bloomberg, the former Mayor of New York, is the majority owner of Bloomberg LP, the owner of Bloomberg News. In 2016, Michael Bloomberg even co-authored an opinion piece with Dimon. The same year, the New York Post reported that JPMorgan Chase was the second largest customer of Bloomberg’s data terminal business with 10,000 leases of Bloomberg’s terminals. At the time, the terminals cost approximately $21,000 each per lease, per year, or about $210 million being paid by JPMorgan Chase to Michael Bloomberg’s company annually. Bloomberg’s data terminals are the cash cow of the company.

The latest spin at Bloomberg News is over the top. On April 17, Bloomberg News posted what is effectively an infomercial for Jamie Dimon but is styled as a news interview. Its title: “When JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon Speaks, the World Listens.” (You can watch the video without the Bloomberg paywall at this YouTube link.)

The interviewer in this piece of puffery is Bloomberg’s Emily Chang. In the opening minutes, Chang says this:

“Jamie Dimon is an institution. Since 2005 he’s been the head of the world’s biggest bank, JPMorgan Chase. He’s widely seen as a rock in the storms of 21st century finance and even at times a kind of guardian of the U.S. and global economy.”

Later in the interview, there is this exchange:

Chang: “You’ve got this reputation of sort of a white knight for the economy. Do you ever feel pressure to come in with the save?”

Dimon: “I feel like a tremendous amount of pressure to do — I’m just, my family comes first. Okay. But to do a great job for my company and our clients. I also feel to do a good job for my country. So, when my country wants me to do something, and we talk all the time to, you know, the Senators and regulators, what can we do to make the system better, to lift up the country, lift up inner cities. We’re trying to figure out how to make this country better. And I do consider that part of our job.”

Against that fanciful alternative reality are these hard facts found in releases from the U.S. Department of Justice and other regulators during Dimon’s tenure at the helm of the bank: charging the bank with laundering money for Bernie Madoff, the largest Ponzi kingpin in U.S. history; charging the bank with using depositors money at its federally-insured bank to gamble in derivatives and lose $6.2 billion; charging the bank with selling toxic mortgages to unknowing investors; charging the bank with “schemes to defraud” the precious metals and United States Treasury market – the market that the U.S. desperately needs to function properly in order to pay its bills.

Last year, JPMorgan Chase settled charges with the Attorney General of the U.S. Virgin Islands, who had credibly charged in a federal lawsuit that the bank “actively participated” in Jeffrey Epstein’s sex trafficking of underage girls by funneling hard cash to him illegally for more than a decade.

Later in the Bloomberg interview, Chang says this:

“Many attribute Dimon’s success to what’s known as the ‘Fortress Balance Sheet.’ Essentially, he takes the cautious approach; never getting so overleveraged that the bank can’t withstand a major unforeseen shock.”

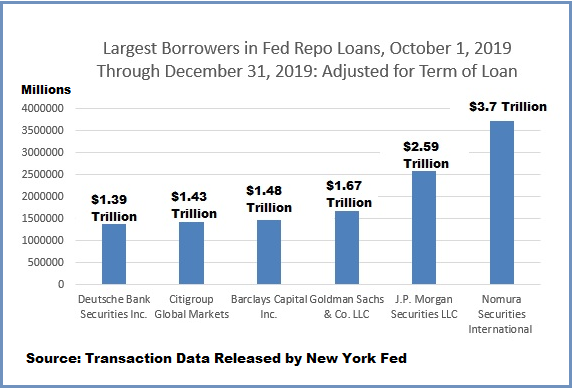

The mirage of a fortress balance sheet at JPMorgan Chase is a running joke among experts in the field. Below is a chart showing that in the last quarter of 2019, the trading unit of JPMorgan Chase became so illiquid that it needed to borrow $2.59 trillion from an emergency repo loan program set up by the Federal Reserve.

Today, JPMorgan Chase’s federal regulators have indicated that they believe the bank is undercapitalized by 25 percent and have proposed new rules to make it raise that needed capital. Dimon is fighting this tooth and nail, going so far as to threaten to file a lawsuit against his own bank regulators.

So along comes the Washington Post, owned by billionaire Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, which has a joint marketing program with the Chase Bank unit of JPMorgan Chase. On Tuesday of last week, the Washington Post Editorial Board decided it would jump into the battle over the amount of capital large banks need to hold to prevent more banking crises and bank bailouts. The editorial suggested that bank regulators didn’t need to demand so much extra capital. (The editorial is behind a paywall.)

Unfortunately, the WaPo Editorial Board grossly misrepresented what constitutes bank capital.

WaPo provided a list of the full 12-members of the Editorial Board who had, ostensibly, penned this editorial or, at least, reviewed it. The names were: Opinion Editor David Shipley, Deputy Opinion Editor Charles Lane and Deputy Opinion Editor Stephen Stromberg, as well as writers Mary Duenwald, Shadi Hamid, David E. Hoffman, James Hohmann, Heather Long, Mili Mitra, Eduardo Porter, Keith B. Richburg and Molly Roberts.

There are plenty of Harvard College graduates in that bunch as well as quite a number of folks who studied at Oxford. It’s difficult to believe that not one of them understands bank capital.

The editorial writers go off the rails in the very first paragraph, writing:

“…This familiar story is playing out once again as regulators around the world seek to impose higher capital requirements on systemically important banks — those deemed ‘too big to fail.’ This is a fancy way of saying they want banks to set aside larger rainy-day funds so they won’t need taxpayer bailouts in the next crisis.”

“Rainy day fund.” Seriously? It was just last month that a financial writer at the New York Times, Andrew Ross Sorkin, had to admit that he had been mischaracterizing bank capital for more than 14 years by calling it a rainy day fund.

As we pointed out at the time:

“…bank capital is not a ‘fund.’ It’s not cash. It’s not liquid assets. It’s an accounting term and a balance sheet item whose components have changed over time. At present, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the federal bank regulator and agency that insures bank deposits up to a maximum of $250,000 per depositor, per bank, bank capital is the following:

‘Common equity tier 1 capital is the most loss-absorbing form of capital. It includes qualifying common stock and related surplus net of treasury stock; retained earnings; certain accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) elements if institution management does not make an AOCI opt-out election, plus or minus regulatory deductions or adjustments as appropriate; and qualifying common equity tier 1 minority interests. The federal banking agencies expect the majority of common equity tier 1 capital to be in the form of common voting shares and retained earnings. [Bold emphasis added.]

‘Additional tier 1 capital includes qualifying noncumulative perpetual preferred stock, bank-issued Small Business Lending Fund (SBLF) and Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) instruments that previously qualified for tier 1 capital, and qualifying tier 1 minority interests, less certain investments in other unconsolidated financial institutions’ instruments that would otherwise qualify as additional tier 1 capital.

‘Tier 2 Capital includes qualifying preferred stock, subordinated debt, and qualifying tier 2 minority interests…’

Why is having a lot of equity capital important for a megabank? Equity capital, and lots of it, is critically important for a bank like JPMorgan Chase because it forces shareholders to take the hit on their investment – and potentially be wiped out – before the losses spill over to the bank’s creditors – which include the mom and pop depositors at its federally-insured bank.

Although the FDIC insures bank deposits (with the unconditional guarantee of the U.S. government standing behind that insurance up to $250,000 per depositor, per bank), in two of the bank collapses that occurred in the spring of last year, the FDIC elected to insure even uninsured depositors to prevent bank runs from spreading across the nation. This created billions of dollars in losses to the FDIC insurance fund. (Those banks were Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.)

The really embarrassing part of the WaPo editorial came in these two sentences:

“Consider Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse a year ago. On paper, the bank had sufficient capital in the form of government bonds purchased before the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates.”

The government bonds were securities purchased by the bank and held on its balance sheet as assets. They were not capital.

If you’ve been getting your information about the safety and soundness of the megabanks on Wall Street from billionaire-owned media, you might want to rethink that strategy.