By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 30, 2023 ~

The Office of Financial Research (OFR) is a unit of the U.S. Treasury Department. OFR was created as part of the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to keep the Financial Stability Oversight Council (F-SOC) informed about emerging threats that have the potential to spread contagion throughout the U.S. financial system — as occurred in 2008 in the worst financial crash since the Great Depression.

Janet Yellen, the U.S. Treasury Secretary, chairs F-SOC. Its members include the heads of every federal banking and Wall Street regulator, who meet regularly to assess any threats on the horizon that could lead to financial instability in the U.S.

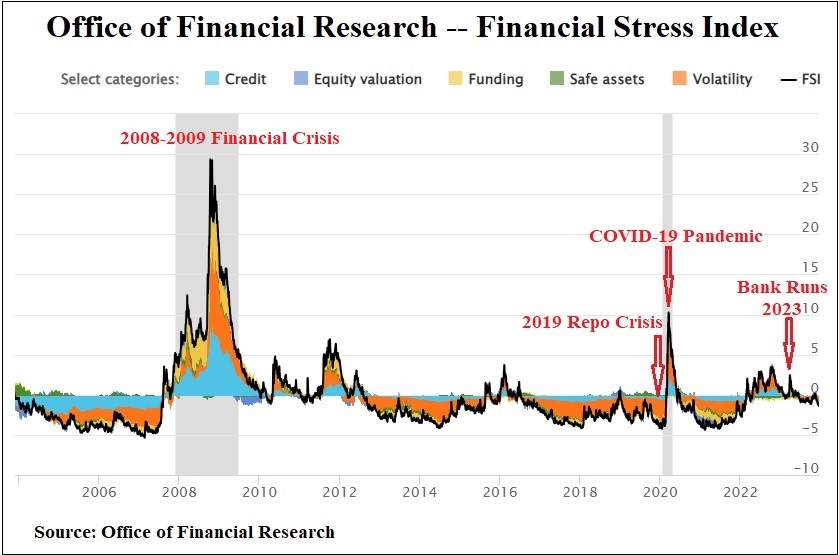

One of the data charts that OFR makes available both to F-SOC and the public to assess accelerating financial problems is its Financial Stress Index. OFR describes that index as follows:

“The OFR Financial Stress Index (OFR FSI) is a daily market-based snapshot of stress in global financial markets. It is constructed from 33 financial market variables, such as yield spreads, valuation measures, and interest rates. The OFR FSI is positive when stress levels are above average, and negative when stress levels are below average.

“The OFR FSI incorporates five categories of indicators: credit, equity valuation, funding, safe assets and volatility.”

Looking at OFR’s Financial Stress Index above, however, one would never know that there have been two major financial crises since the 2008 crisis – not counting the financial crisis that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Financial Stress Index failed to send a warning prior to the Fed making trillions of dollars in emergency repo loans beginning on September 17, 2019 and it also failed to send a warning prior to the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history that occurred in a seven week span this past spring.

Since this Financial Stress Index clearly isn’t working as an early warning mechanism, why is it still being touted on the website of the OFR? Our theory is that it is one of numerous mechanisms used to delude the American people into thinking that federal banking regulators know what’s going on inside the U.S. banking system when recent history has shown, time and again, that they clearly do not know what is going on.

Let’s start with the repo loan crisis in the fall of 2019, which resulted in the Fed making enormous emergency loans to Wall Street trading houses.

On September 17, 2019 the overnight loan rate spiked from an average of about 2 percent in previous days to 10 percent – signaling that one or more financial firms were in trouble. Liquidity became so stressed on Wall Street that the Fed began making billions of dollars in emergency repo loans available daily to 24 trading houses on Wall Street, the majority of which were owned by the mega banks. The Fed released on a daily basis the dollar amounts it was loaning, but withheld the names of the specific banks and how much they had borrowed that day, or cumulatively. This made it impossible for the public to see which Wall Street firms were experiencing the most severe liquidity crisis.

It was the first time the Fed had intervened in the repo market since the 2008 financial crash – another crisis that federal banking regulators did not see coming.

In September 2019, the COVID-19 related financial crisis remained months away, so COVID had nothing to do with the onset of the financial strains of September 2019. The first reported case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was not reported by the CDC until January 20, 2020 and the World Health Organization did not declare a pandemic until March 11, 2020.

The dollar amounts of the Fed’s emergency repo loans grew to staggering levels. On October 24, 2019, we reported the following:

“The New York Fed will now be lavishing up to $120 billion a day in cheap overnight loans to Wall Street securities trading firms, a daily increase of $45 billion from its previously announced $75 billion a day. In addition, it is increasing its 14-day term loans to Wall Street, a program which also came out of the blue in September, to $45 billion. Those term loans since September have been occurring twice a week, meaning another $90 billion a week will be offered, bringing the total weekly offering to an astounding $690 billion. It should be noted that if the same Wall Street firms are getting these loans continuously rolled over, they are effectively permanent loans. (That’s exactly what happened during the 2007-2010 Wall Street collapse: some teetering Wall Street casinos received, individually, $2 trillion in cumulative loans that were rolled over for two and one-half years – without the authorization or even awareness of Congress or the American people. One bank, Citigroup, received over $2.5 trillion in Fed loans, much of them at an interest rate below 1 percent, at a time when it was insolvent and couldn’t have obtained loans in the open market at even high double-digit interest rates.)”

The Fed’s emergency repo loan program lasted from September 17, 2019 until July 2, 2020, by which time the Fed had resurrected the alphabet soup list of emergency loan programs from 2008 (and others) in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, the Fed was legally required to release the names of the banks and the amounts they borrowed “on the last day of the eighth calendar quarter following the calendar quarter in which the covered transaction was conducted.”

Those Fed revelations, that had been withheld from the American people for two years, should have made front page headlines in newspapers and on the digital front pages of every major business news outlet. Instead, there was a universal news blackout of the story at the largest business news outlets, including: Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal, the business section of the New York Times, the Financial Times, Dow Jones’ MarketWatch, and Reuters.

Let that sink in carefully for a moment. The same reporters who had covered the onset of the repo crisis and the Fed’s response to it initially, for some strange reason had no interest in telling the American people which Wall Street banks had gotten the lion’s share of all that cheap money from the Fed. Even after Wall Street On Parade published the data and provided it to the reporters, the mainstream media news blackout continued.

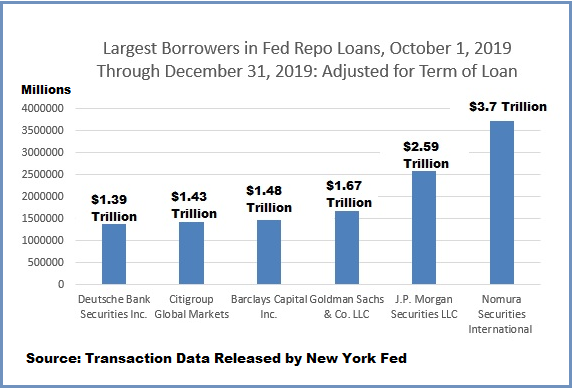

When we downloaded the Fed’s emergency repo loans directly from the Fed for the fourth quarter of 2019, and adjusted them for the term of the loan (some terms ran as long as 42 days) it became apparent that the Fed had pumped staggering sums into Wall Street trading firms – in advance of the pandemic.

When we tallied the Fed’s “trade amount” column for the fourth quarter of 2019, the emergency repo loans came to $4.5 trillion. But when we set up a new column that adjusted the loans by the number of days in the term, the Fed’s repo loans for the fourth quarter of 2019 came to $19.87 trillion, or 4.4 times the “trade amount” column.

Just six trading houses received 62 percent of the $19.87 trillion, as illustrated in the chart below. The parents of three of those firms, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Goldman Sachs, are shareowners of the New York Fed, the regional Fed bank that funneled the emergency loans to the Wall Street banks in 2019 as well as in 2008. The New York Fed is allowed to electronically create the trillions of dollars it loans out at the push of a button.

Next, let’s take a look at this year’s spring banking crisis.

In the span of seven weeks this past spring, running from March 10 to May 1, the second, third, and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history occurred. In order of size, those were: First Republic Bank (May 1), Silicon Valley Bank (March 10) and Signature Bank (March 12). (The largest bank failure in U.S. history, Washington Mutual, occurred in 2008 during the financial crisis.)

In the failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) took the drastic step of bailing out uninsured depositors alongside insured depositors in order to stop the kind of systemic contagion that erupted with the fall of Lehman Brothers in 2008. In a recent report, the FDIC has put the losses to its Deposit Insurance Fund at $16.3 billion from protecting uninsured depositors at those two banks.

And, once again, the Federal Reserve stepped in with yet another bailout program, this time called the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). The Fed is already the lender of last resort to banks with short-term loans from its Discount Window, but, apparently, the banks wanted long-term loans – something that the Federal Reserve Act has never envisioned as a legitimate role for the Fed. And yet, under the BTFP, the Fed provided loans of up to one year and will value the bonds put up as collateral at par (full face amount) instead of at their deeply underwater market value. According to the Fed’s weekly H.4.1 report, as of Wednesday, November 22, the BTFP had $114 billion in loans still outstanding.

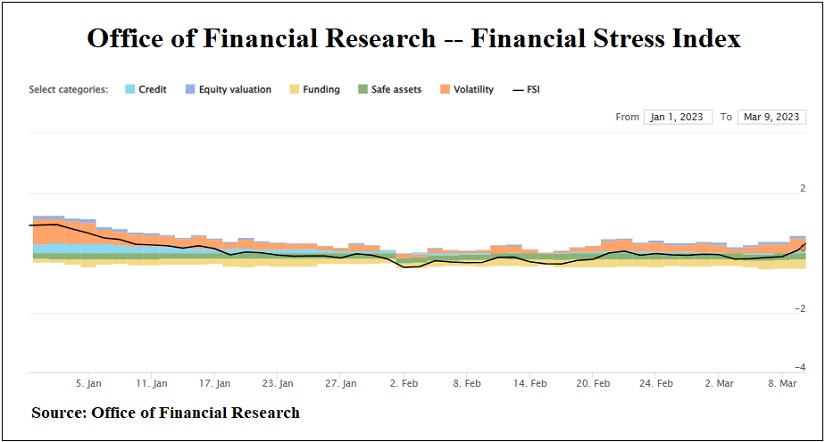

Also, once again, as the Financial Stress Index chart below indicates, it failed to send any advance warning to F-SOC that the second, third and fourth largest bank failures in U.S. history were about to occur with unprecedented speed.