By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 7, 2023 ~

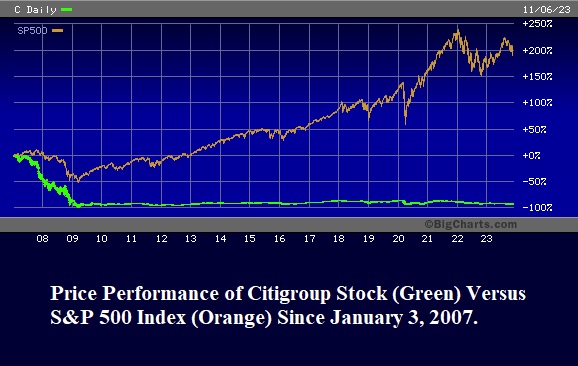

On the first day of trading in January 2007 (the year prior to the Wall Street financial crisis in 2008 that saw century-old iconic financial firms explode one after another), Citigroup closed the trading day at $55.25. Yesterday, Citigroup’s common stock closed at an effective share price of $4.20.

Citigroup did a 1-for-10 reverse stock split on May 9, 2011. That means that investors holding 100 shares of Citigroup back in January 2007 saw their position shrink to 10 shares after May 9, 2011. So yesterday’s closing price of $42.04 for Citigroup is effectively $4.20 for long-term shareholders, adjusting it for the reverse stock split.

To put that in even starker terms, investors who have held onto this dog for almost 17 years have watched 92 percent of its share price vanish.

More dire news on Citigroup came yesterday with a report at CNBC indicating that Citigroup may cut as many as 24,000 employees, or 10 percent of its workforce of 240,000.

The big question is, what on earth is Citigroup doing with that many workers in the first place?

According to data from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Citigroup’s federally-insured bank, Citibank, ranks as the third largest U.S. bank by assets. As of June 30, according to the Fed, Citibank had just 660 domestic bank branches versus 3,803 domestic bank branches for the second largest bank by assets, Bank of America. (See the Fed data at this link.)

According to Bank of America’s 10-K (Annual Report) for year-end 2022, it employed 217,000 workers, almost 10 percent less than Citigroup’s Citibank while having 5.76 times the number of domestic bank branches.

In addition, Bank of America owns the giant retail brokerage firm, Merrill Lynch, which as of August of 2022 was staffing 560 separate branch offices according to AdvisorHub. Citigroup sold its retail brokerage operation (Smith Barney) to Morgan Stanley following the financial crisis in 2008.

Federal regulators are likely carefully monitoring the situation at Citigroup because the bank blew itself up in 2008 with toxic subprime debt bombs residing off its balance sheet and complex derivatives. Citigroup’s stock traded at 99 cents in March 2009. It took $2.5 trillion in secret cumulative loans from the Fed from December 2007 to July 2010 to resuscitate Citigroup’s sinking hulk. (An audit of the Fed’s secret emergency bailout facilities by the Government Accountability Office revealed this information to the American people in July 2011.)

This is how we reported the situation at Citigroup on November 24, 2008 in the midst of the worst Wall Street crash since the Great Depression:

“As of last Friday’s close, Citigroup had $2 trillion in ‘assets’ and $20.5 billion in stock market value, strongly suggesting the term ‘assets’ is a misnomer on Wall Street. Late last night the U.S. government agreed to dump hundreds of billions more into this black hole without any survival plan required of the company as demanded of the auto makers: apparently if you make those four-wheel machines that get us to work you’re suspect; if you manufacture losses in unintelligible derivatives, you’re good to go.

“Citigroup’s five-day death spiral last week was surreal. I know 20-something newlyweds who have better financial backup plans than this global banking giant. On Monday came the Town Hall meeting with employees to announce the sacking of 52,000 workers. (Aren’t Town Hall meetings supposed to instill confidence?) On Tuesday came the announcement of Citigroup losing 53 percent of an internal hedge fund’s money in a month and bringing $17 billion of assets that had been hiding out in the Cayman Islands back onto its balance sheet. Wednesday brought the cheery news that a law firm was alleging that Citigroup peddled something called the MAT Five Fund as ‘safe’ and ‘secure’ only to watch it lose 80 per cent of its value. On Thursday, Saudi Prince Walid bin Talal, from that visionary country that won’t let women drive cars, stepped forward to reassure us that Citigroup is ‘undervalued’ and he was buying more shares. Not having any Princes of our own, we tend to associate them with fairytales. The next day the stock dropped another 20 percent with 1.02 billion shares changing hands. It closed at $3.77.

“Altogether, the stock lost 60 per cent last week and 87 percent this year. The company’s market value has now fallen from more than $250 billion in 2006 to $20.5 billion on Friday, November 21, 2008. That’s $4.5 billion less than Citigroup owes taxpayers from the U.S. Treasury’s bailout program.

“Also rounding out the week’s news on Friday was the revelation that after receiving $25 billion of taxpayer money, Citigroup would continue to honor its $400 million, 20-year commitment and pay out an installment of $20 million to have the new Mets’ baseball stadium named Citi Field. (Flashback: April 7, 1999: Enron agrees to pay more than $100 million over 30 years to name a Houston stadium Enron Field.)”

One of the key factors that may be making Citigroup’s federal regulators nervous today is its massive amount of uninsured deposits.

In a speech delivered by FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg on October 4, he made it very clear that the FDIC is concerned about both the total amount of uninsured deposits in the U.S. banking system and the concentration of those uninsured deposits among a handful of mega banks.

Gruenberg noted in his speech that year-end data for the three banks that failed this past spring showed that anywhere from 90 percent to 70 percent of their deposits were uninsured. (During a banking panic, uninsured deposits usually make the fastest beeline for the exits.)

According to federal banking reports filed with regulators for the quarter ending June 30 (call reports), the four largest U.S. banks by assets (JPMorgan Chase Bank, Bank of America, Citibank and Wells Fargo) accounted for $4.185 trillion of uninsured deposits, or 59 percent of all uninsured deposits at all 4,645 federally-insured institutions.

Citibank indicates in its call report for June 30 that 85.5 percent of its $1.338 trillion in total deposits are uninsured. The breakdown is as follows: It has $548.33 billion in uninsured deposits in its domestic offices plus $595.4 billion in deposits in foreign offices. (The FDIC does not insure deposits on foreign soil.) Those two figures tally up to $1.144 trillion in deposits lacking FDIC insurance out of a total deposit base of $1.338 trillion.

The breakdown for the other three mega banks as of June 30 are as follows: 59 percent of JPMorgan Chase’s deposits lack FDIC insurance; 49 percent at Bank of America; and 51 percent at Wells Fargo.

Deposits in domestic bank offices in the U.S. that exceed $250,000 per depositor/per bank are not insured by the FDIC.

The staggering amount of uninsured deposits at the mega banks is not a problem for the vast majority of federally-insured banks in the U.S. according to Gruenberg. In his speech on October 4, he said that “As of December 2022, more than 99 percent of deposit accounts were under the $250,000 deposit insurance limit.”