By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 26, 2023 ~

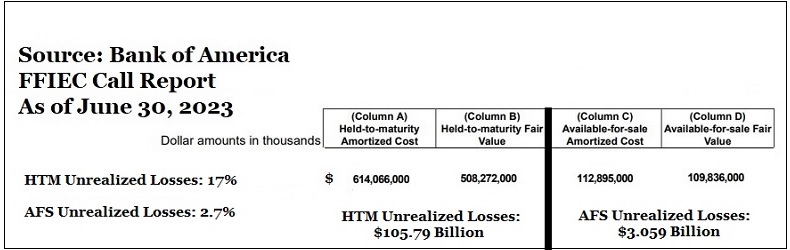

According to Bank of America’s federal regulatory filing known as the Call Report, for the quarter ending June 30, 2023, it had $105.79 billion in unrealized losses on its held-to-maturity (HTM) securities. That figure is not only far beyond the realm of what its peer banks reported, but it represents a stunning 34 percent of all unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities reported by 4,645 FDIC-insured commercial banks and savings institutions as of June 30, according to the FDIC’s Quarterly Banking Profile.

For the quarter ending June 30, the FDIC reported that all 4,645 FDIC-insured financial institutions had $309.6 billion in unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities.

Held-to-maturity securities at the largest banks are made up predominately of federal agency mortgage-backed securities and U.S. Treasury bills, notes and bonds. The principal on these securities is federally guaranteed at maturity but their market value is a function of the level of prevailing interest rates at a particular moment in time. At this particular moment in time, the Fed has hiked interest rates 11 times since March 17 of last year, pushing some interest rates on recently issued debt securities to their highest levels in 16 years. When interest rates rise dramatically, they impose market value losses on similar debt securities that were issued in the past when interest rates were much lower.

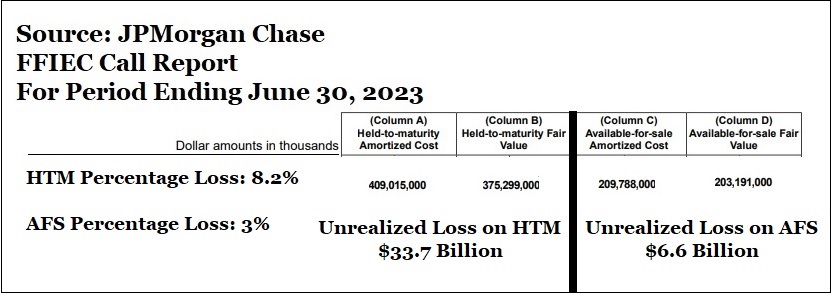

What the decline in bond market values as a result of higher interest rates doesn’t explain, however, is why Bank of America’s losses on these debt securities are so far beyond those of its peers. As of June 30, Bank of America showed a 17 percent loss on its held-to-maturity debt securities versus 8.2 percent at JPMorgan Chase and 9.26 percent at Citibank – the mega bank that blew itself up in 2008, ended up as a 99-cent stock in 2009 and got a $1.2 trillion secret bailout from the Fed to shore it back up.

Is it possible that JPMorgan Chase and Citibank are using a far more forgiving model to value their debt securities?

We emailed the press contact for Bank of America yesterday, inquiring as to why their unrealized losses are so much larger than their peer banks. We asked for a response by last evening. We received no response.

Not only are Bank of America’s unrealized losses beyond the norm on a percentage basis, but the total dollar amount of its held-to-maturity securities are also far beyond the norm.

In terms of assets, Bank of America is the second largest federally-insured bank in the U.S. with $2.4 trillion in assets. (That’s just the federally-insured commercial bank unit of Bank of America. The bank holding company has $3.1 trillion in assets and includes the giant retail brokerage firm and investment bank, Merrill Lynch.) JPMorgan Chase is the largest bank in the U.S. with $3.38 trillion in assets at its federally-insured bank (Chase Bank) and $3.87 trillion in assets at its holding company.

Despite being second in size to JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America reported $614 billion in held-to-maturity securities as of June 30 versus $409 billion reported by JPMorgan Chase. (Those figures come from the federally insured banking units, not the holding companies.) Why does Bank of America have $205 billion more of these debt securities than the global behemoth JPMorgan Chase? No one seems willing to talk about it.

To understand why the accounting category of held-to-maturity is so attractive to the mega banks and dangerous for the public, we offer this take from CPA/CFA Sandy Peters, who posted the following at the CFA Institute website. Peters writes:

“What that means is that the financial statement carrying value of those financial instruments held-to-maturity is reflected at amortized cost, or what management paid for the asset sometime in the past plus amortization of the discount or premium from the face value. The fair value is only disclosed on the face of the financial statement and in the footnotes. Any unrealized loss is ‘hidden in plain sight.’

“But management intent and business model do not change the value of financial instruments. The HTM classification only makes it harder for investors and depositors to see.”

To put that in even sharper focus, losses on these securities do not hit the income statement of these banks.

Peters goes on to explain how this all played out at the now collapsed Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), which went into receivership at the FDIC on March 10, creating billions of dollars in losses for the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund and a contagion effect at other banks:

“This is what SVB did. At 12/31/2022, SVB reflected $91.3 billion of HTM financial instruments, 43.1% of its balance sheet, at amortized cost. Their fair value was only $76.2 billion, or $15.1 billion less than their carrying value. With only $16.3 billion in book equity, this loss would have reduced equity, assuming the losses had no tax benefit, to $1.2 billion. Even with a tax benefit — if SVB could recoup all the tax benefit — this would amount to a $11.9 billion reduction in book equity…”

Peters calls this “Hide-‘til-Maturity” accounting. In the case of SVB, it was hide ’til bank run accounting.