By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: June 20, 2023 ~

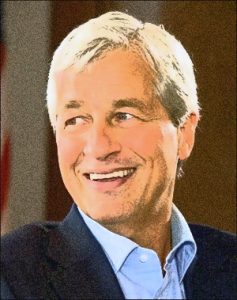

The tenure of Jamie Dimon as Chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, the largest federally-insured bank in the United States and the largest trading casino on Wall Street, has copiously revealed the following: the bank is more than willing to look the other way at crime if it means an increase in assets, profits or business referrals.

Each of those three ingredients were present in the bank’s decades long involvement with Bernie Madoff, with its Chinese Princeling scandal and in the unfolding details of its intimate relationship with child sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein.

This reality may be difficult for the New York business press to acknowledge – since it has mostly covered Jamie Dimon as the grand statesman of Wall Street – but this is the hard reality nonetheless.

Yesterday, the Wall Street Journal’s Khadeeja Safdar and David Benoit revealed the contents of a 22-page internal report that JPMorgan Chase had prepared in 2019 as a timeline of its relationship with Jeffrey Epstein. The bank was apparently attempting to assess its liability after Epstein was arrested on July 6, 2019 by the Justice Department and charged with sex trafficking. (Epstein was found dead in his jail cell on August 10, 2019. The Medical Examiner ruled his death a suicide.)

The 22-page internal report had been filed under seal with the federal district court in Manhattan that is hearing two lawsuits against the bank for aiding and abetting Epstein’s sex trafficking. Apparently, someone leaked the full contents of the report to the reporters. One paragraph of the Wall Street Journal article is particularly enlightening. It reads as follows:

“The 2019 JPMorgan report said that Epstein had appeared to have forged close relationships with senior executives and government officials, including Dubai’s Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem and British politician Peter Mandelson. Epstein tried to connect these associates to Staley and the bank for business deals and international expansions.”

The reference to “Staley” is to Jes Staley, a former executive of the bank who worked a few hundred feet from Dimon’s office, according to a deposition given by Dimon. Disturbing internal emails show that Staley was closely aligned with Epstein, even visiting him while he was serving his sentence for sex with a minor. Now consider the above paragraph in combination with what Virginia Giuffre has alleged in her prior lawsuits against Epstein: that, beginning when she was just 17 years old, Epstein and his girlfriend/procurer, Ghislaine Maxwell, arranged sexual encounters for Giuffre with royalty and powerful politicians. Prince Andrew settled monetary damages with Giuffre last year.

To put it simply, Epstein was an asset gatherer, and profit gatherer, and new business gatherer for JPMorgan Chase. And he dangled sex with underage women as an inducement to get meetings and make connections. And that is why, despite Epstein’s conviction in 2008 for procuring sex with a minor, despite his forced registration as a life-long sex offender, and despite his settling of dozens of cases of sexual assault of minors, JPMorgan Chase retained him as a client from 1998 to 2013.

There is a serious and deeply disturbing pattern of looking the other way at crime in order to gain a business advantage at JPMorgan Chase under Jamie Dimon’s “stewardship.”

In November 2016, units of JPMorgan Chase agreed to pay more than $264 million to the U.S. Department of Justice, the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Reserve in what was widely known as its Chinese “Princeling” scandal.

In announcing the settlement in the Princeling scandal in 2016, officials at the Justice Department said this:

“The so-called Sons and Daughters Program was nothing more than bribery by another name…Awarding prestigious employment opportunities to unqualified individuals in order to influence government officials is corruption, plain and simple. This case demonstrates the Criminal Division’s commitment to uncovering corruption no matter the form of the scheme…

“In this case, JPMorgan employees designed a program to hire otherwise unqualified candidates for prestigious investment banking jobs solely because these candidates were referred to the bank by officials in positions to award business to the bank. In certain instances, referred candidates were hired with the understanding that the hiring was linked to the award of specific business. This is no longer business as usual; it is corruption.”

In January 2014, JPMorgan Chase paid $2.6 billion in fines and restitution, signed a deferred prosecution agreement with the Justice Department, and walked away from their 22-year involvement with Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi scheme.

After digesting the related documents released by the Justice Department in the Madoff matter, the Los Angeles Times asked the following: “Bernie Madoff: Was he part of the JPMorgan ring, or was JPMorgan part of his ring?”

The same thing could now be asked in the Epstein matter: Was Epstein part of the JPMorgan ring or was JPMorgan part of Epstein’s ring?

The Justice Department prosecutors who settled the case against JPMorgan Chase used much of the investigative material from Irving Picard, the Trustee of the Madoff victims’ fund, to bring their charges against JPMorgan Chase. According to Picard, JPMorgan Chase used unaudited financial statements from Madoff and skipped the required steps of bank due diligence to make $145 million in loans to Madoff’s business.

Lawyers for Picard write that from November 2005 through January 18, 2006, JPMorgan Chase loaned $145 million to Madoff’s business at a time when the bank was on “notice of fraudulent activity” in Madoff’s business account and when, in fact, Madoff’s business was insolvent. The reason for the JPMorgan Chase loans was because Madoff’s business account was “reaching dangerously low levels of liquidity, and the Ponzi scheme was at risk of collapsing.” JPMorgan, in fact, “provided liquidity to continue the Ponzi scheme,” according to Picard.

But was Madoff also generating new business deals or profits for JPMorgan Chase? The accounts of Norman F. Levy come immediately to mind.

JPMorgan Chase and its predecessor banks extended tens of millions of dollars in loans to Norman F. Levy and his family so they could invest with the insolvent Madoff. (Levy died in 2005 at age 93 without being charged with any crimes.)

According to Picard, Levy had $188 million in outstanding loans in 1996, which he used to funnel money into Madoff investments. Picard’s lawyers told the court that JPMorgan Chase referred to these investments as ‘special deals,’ and adding:

“Indeed, these deals were special for all involved: (a) Levy enjoyed Madoff’s inflated return rates of up to 40% on the money he invested with Madoff; (b) Madoff enjoyed the benefits of large amounts of cash to perpetuate his fraud without being subject to JPMC’s due diligence processes; and (c) JPMC [JPMorgan Chase] earned fees on the loan amounts and watched the ‘special deals’ from afar, escaping responsibility for any due diligence on Madoff’s operation.”

A critical piece of evidence against JPMorgan was that despite funneling loans to both Madoff and Levy, the bank “advised the rest of its Private Bank customers not to invest with Madoff,” according to Picard.

On paper, according to Picard, Levy was worth $1.5 billion in 1998. He was such an important customer to JPMorgan and its predecessor firms that he was given his own office at the bank.

Levy was a commercial real estate broker and, according to a 2009 Vanity Fair article, at one point Levy “had an ownership stake in 70 properties, including the Seagram Building and 21 shopping centers across America…”

According to Picard, once Levy was a Madoff client, the relationship included classic, unchecked evidence of money laundering for years and years that should have resulted in legally-mandated Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed with the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN). But even after a different bank detected the suspicious activity in the late 1990s and reported the transactions to FinCEN, JPMorgan Chase and its predecessor banks failed to file their own mandated SARs. JPMorgan Chase not only allowed the activity to continue but allowed it to increase dramatically in dollar terms.

Contrast the above with information that James Dalessio, an employee of JPMorgan Chase, emailed to colleagues in October 2007 regarding Epstein’s cash withdrawals from the bank. Dalessio informed a control group at JPMorgan’s Private Bank that Epstein had withdrawn the following cash amounts in just a two-year span: 10 withdrawals of $40,000 year-to-date in 2007; cash withdrawals totaling $914,796 in 2006 consisting of 18 withdrawals of $40,000 in cash; two withdrawals of $60,000 in cash; one withdrawal of $30,000 in cash; and one withdrawal of $25,000 in cash. (Dalessio’s email was submitted to the Court, unsealed, in the pending U.S. Virgin Islands v JPMorgan Chase Bank case.)

Dalessio notes in his email that CTRs (Currency Transaction Reports) were filed for these cash withdrawals but there is no indication that Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) were filed with FinCEN.

The U.S. Virgin Islands is alleging the following in its lawsuit against JPMorgan Chase:

“Plaintiff, the Government of the United States Virgin Islands (‘Government’), claims and will prove that Defendant JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (‘JPMorgan’) violated the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, 18 U.S.C. §§ 1581-1597 (‘TVPA’), by knowingly participating in and benefitting from Jeffrey Epstein’s sex-trafficking and by obstructing investigation through its concealment of Epstein’s suspicious transactions from law enforcement. Discovery confirms that JPMorgan knowingly, recklessly, and unlawfully provided and pulled the levers through which Epstein’s recruiters and victims were paid and was indispensable to the operation and concealment of Epstein’s trafficking. JPMorgan had real-time information on Epstein’s payments that the Government did not and had specific legal duties to report this information to law enforcement authorities, which it intentionally decided not to do.”

JPMorgan Chase’s unprecedented history of crimes has another distinction. It is the only U.S. domiciled bank that we know of that was compared to the Gambino crime family in a book authored by two trial attorneys.

In 2016, trial lawyers Helen Davis Chaitman and Lance Gotthoffer released the book JPMadoff: The Unholy Alliance Between America’s Biggest Bank and America’s Biggest Crook. Chaitman and Gotthoffer provide this analysis: (JPMC stands for JPMorgan Chase.)

“In Chapter 4, we compared JPMC to the Gambino crime family to demonstrate the many areas in which these two organizations had the same goals and strategies. In fact, the most significant difference between JPMC and the Gambino Crime Family is the way the government treats them. While Congress made it a national priority to eradicate organized crime, there is an appalling lack of appetite in Washington to decriminalize Wall Street. Congress and the executive branch of the government seem determined to protect Wall Street criminals, which simply assures their proliferation.”

Chaitman and Gotthoffer then suggested using the RICO statute to prosecute the bank, writing:

“If Jamie Dimon is running a criminal institution, he should be prosecuted for it. And law enforcement has the perfect tool for such a prosecution: the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations ACT (RICO).

“Congress enacted RICO in 1970 in order to give law enforcement the statutory tools it needed to prosecute the people who committed crimes upon orders from mob leaders and the mob leaders themselves. RICO targets organizations called ‘racketeering enterprises’ that engage in a ‘pattern’ of criminal activity, as well as the individuals who derive profits from such enterprises. For example, under RICO, a mob leader who passed down an order for an underling to commit a serious crime could be held liable for being part of a racketeering enterprise. He would be subject to imprisonment for up to twenty years per racketeering count and to disgorgement of the profits he realized from the enterprise and any interest he acquired in any business gained through a pattern of ‘racketeering activity.’ ”

To date, the U.S. Department of Justice has charged JPMorgan Chase with five felony counts between 2014 and 2020. In each case, the bank admitted to the charges and in each case the Justice Department gave it a deferred prosecution agreement, meaning it was put on probation and had to promise not to engage in more crimes. Nonetheless, the crimes continued. In the Princeling scandal, the bank was given a non-prosecution agreement.

Astonishingly, the Board of Directors of JPMorgan Chase did not see this unprecedented pattern of crime on Jamie Dimon’s watch as sufficient grounds to fire him. Instead, the Board made Dimon a billionaire with stock awards and bonuses. (See our report: If You’re Baffled as to Why JPMorgan Chase’s Board Hasn’t Sacked Jamie Dimon as the Bank Racked Up 5 Felony Counts – Here’s Your Answer.)