By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: September 23, 2019 ~

WeWork’s business model isn’t workable. Everybody understands that except the Wall Street bank that has the most to lose if WeWork’s initial public offering (IPO) of its stock doesn’t move forward. That bank is JPMorgan Chase, one of the two main underwriters of the IPO, along with Goldman Sachs.

WeWork’s business model is to take long-term leases in commercial office buildings and then sub-lease that space under short leases to small businesses, start-ups and freelancers – none of which are particularly known for their ability to pay rent in a downturn. WeWork is currently on the hook for more than $47 billion in long term leases while it has yet to figure out how to make a dime of profits.

JPMorgan Chase is so interconnected with WeWork that to a number of minds WeWork looks like little more than a strawman for the bank and the bank’s biggest commercial real estate clients in New York City where WeWork is taking vacant space off the market at seismic speed. WeWork is now the largest office tenant in New York City.

The interconnections between WeWork and JPMorgan Chase include the following: JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., a federally insured bank, “has made loans and extended credit to Adam Neumann totaling $97.5 million across a variety of lending products, including mortgages secured by personal property and unsecured credit lines and letters of credit,” according to the prospectus filed with the SEC for the recently aborted IPO.

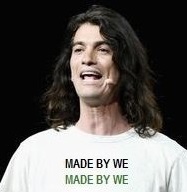

Neumann is Chairman, CEO and co-founder of WeWork. Together with his wife, Rebekah, Neumann put a good chunk of those loans from JPMorgan Chase to work diversifying his asset base away from his speculative IPO and into five personal residences for his family in upscale communities. The tally for the homes comes to more than $80 million.

JPMorgan Chase is also one of three banks that has given Neumann a $500 million line of credit, which he had drawn down to the tune of $380 million as of July 31, 2019. That whopping line of credit is secured by shares of stock in The We Company, the parent of WeWork. Unfortunately for JPMorgan Chase, the valuation for The We Company has been melting faster than a snow cone in July. The initial buzz around the WeWork IPO was that the company could have a valuation of over $60 billion. Then there was talk of a $47 billion valuation, which is where its largest investor, a Japanese investment fund operated by SoftBank, last bought private shares. The valuation continued to come down to around $15 billion, and still failed to find enough interest to launch an IPO.

This raises the question as to what, exactly, is backing the $380 million that Neumann has drawn down from the banks.

JPMorgan Chase also provided a $600 million loan in order for WeWork to be lauded in the press as having purchased the landmark Lord & Taylor building at 424 Fifth Avenue for $850 million. But, according to the prospectus for the WeWork IPO, the company itself only put up $50 million while other entities like the Rhône Group and other investors own the bulk of the building. In other words, over 70 percent of the funds for the purchase of a troubled piece of real estate on Fifth Avenue came from JPMorgan Chase, not from the profits of WeWork’s grand business model.

In fact, WeWork has never made any profits in its nine years of existence and its losses are alarmingly out of control. The company lost $1.6 billion last year and its losses have spiraled to over $900 million in just the first half of this year.

JPMorgan Chase is also a major lender to real estate developers and building owners in Manhattan. Many of these same developers and building owners are benefitting from WeWork signing long-term leases that dramatically shrink the vacancy rate in their buildings. JPMorgan Chase’s real estate clients who have signed deals with WeWork include Rudin Management; L&L Holding Company; and Midwood Investment and Development, to name just a few.

In the case of Rudin Management, whose CEO, Bill Rudin, was also an early investor in WeWork, a curious thing happened with its 110 Wall Street building in lower Manhattan. The building is fully occupied with one tenant, WeWork, whose long-term lease runs until 2041. The building was constructed by Bill Rudin’s grandfather, Sam Rudin, more than half a century ago and has been owned by Rudin Management ever since. This spring, Rudin Management put the building up for sale. The selling documents explained in excruciating detail the risks of having WeWork as the sole occupier of the space. The building was pulled from the sales block just a few months after it was offered.

The negative factors mentioned in the offering memorandum for 110 Wall Street pale in comparison to having the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston take a machete to your business model in front of a packed audience at the Stern School of Business at NYU. That’s what happened this past Friday.

Eric Rosengren, the President of the Boston Fed, delivered a speech at NYU and singled out WeWork for having a dangerous business model that could threaten financial stability and losses at its bank lenders. Rosengren stated:

“First, co-working companies – which enter into long-term leases with the property owners – have tended to re-lease to smaller-sized and less mature companies on a shorter-term basis. This segment of the economy is likely to be particularly susceptible to an economic downturn, potentially resulting in office vacancies rising more quickly than they have historically. Thus, in a downturn the co-working company would be exposed to the loss of tenant income, which puts both them and the property owner at risk if they cannot make lease payments to the owner of the building.

“A second reason for concern is that some companies may utilize bankruptcy-remote special purpose entities, or SPEs, for leases. This structure may allow the co-working company to potentially walk away from unprofitable lease arrangements in an economic downturn without the property owner having recourse to the ultimate parent, the co-working company. Simply put, I am concerned that commercial real estate losses will be larger in the next downturn because of this growing feature of the real estate market, which could ultimately make runs and vacancies more likely due to this new leasing model.

“The fact that the shared office model relies on small-company tenants with short-term leases, combined with the potential lack of recourse for the property owner, is potentially problematic in a recession. This also raises the issue of whether bank loans to property owners in cities with major penetration by co-working models could experience a higher incidence of default and greater loss-given-defaults than we have seen historically.”

Sure enough, we checked the WeWork prospectus and it says this: “…our leases are often held by special purpose entities….”

This is a list of 64 buildings in New York City where WeWork holds leases or has an ownership stake. The Lord & Taylor building at 424 Fifth Avenue is likely not listed because it is still under renovation.