By Pam Martens: January 7, 2019 ~

On Sunday, December 23, 2018, the sitting U.S. Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, lit up the airwaves with the announcement on his Twitter page that he had “convened individual calls with the CEOs of the nation’s six largest banks.” The Tweet went downhill from there.

The Tweet attached a press release from the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Public Affairs which named the six banks and their CEOs involved in the calls. They were Brian Moynihan, Bank of America; Michael Corbat, Citigroup; David Solomon, Goldman Sachs; Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan Chase; James Gorman, Morgan Stanley; and Tim Sloan at Wells Fargo. Mnuchin said he asked the bank CEOs about their liquidity to fund regular operations and they told him they had “ample liquidity.”

Let’s pause right there for a moment. These are the same Wall Street banks that brought the U.S. financial system to its knees just a decade ago while consistently lying to their regulators about their embedded risks. Mnuchin asking them in a phone call from Mexico while he’s on a luxury vacation to fess up to him is the stuff of sitcoms. (Unfortunately, we don’t have a weird photograph to commemorate the calls as we do when Mnuchin and his actress wife, Louise Linton, visited the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in November 2017 to flash some freshly minted U.S. currency with Mnuchin’s signature.)

In the leadup to the big crash of 2008 there was the big lie that the Wall Street banks had placed their derivative trades with counterparties who had properly reserved to pay them off – leaving the taxpayer to bail out the feckless AIG insurance company to the tune of $185 billion. There was the big lie at Citigroup that it was as sound as the other big banks when, in fact, it turned out that it was insolvent and needed the largest bailout in global banking history. By the time the dust settled, Citigroup had received $2.5 trillion cumulatively in secret, almost zero-interest-rate loans from the Federal Reserve; $45 billion in capital from the U.S. Treasury; over $300 billion in asset guarantees from the Federal government; while the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) guaranteed $5.75 billion of its senior unsecured debt and $26 billion of its commercial paper and interbank deposits.

Goldman Sachs was offloading its dubious mortgage products to unsuspecting investors while it was shorting the market to cash in on the coming housing meltdown. JPMorgan’s veracity with its regulators can be summed up by this assessment from former Senator Carl Levin who oversaw the investigation of its London Whale derivatives scandal of 2012 as Chair of the U.S. Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations and issued a 300-page report. Levin said JPMorgan “piled on risk, hid losses, disregarded risk limits, manipulated risk models, dodged oversight, and misinformed the public.”

Rather than Mnuchin shoring up confidence with his calls to the banks, the stock market tanked on the following trading day, Monday, December 24, making it the worst plunge for the S&P 500 on Christmas eve in U.S. history. The Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 651 points.

This is not the first time that Mnuchin has caused markets to plunge. There was his comment on the U.S. dollar on January 24 of last year while attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland that sent the dollar cascading to a three-year low. Mnuchin said “Obviously a weaker dollar is good for us as it relates to trade and opportunities.” As a former 17-year veteran of Goldman Sachs, Mnuchin should know that talking down the dollar at an event attended by 500 journalists from around the world is really bad form for a sitting U.S. Treasury Secretary. He attempted to walk back the comment the next day on CNBC, stating “In the longer term, we fundamentally believe in the strength of the dollar.”

What Mnuchin also succeeded in doing on Christmas Eve was to shave tens of billions of dollars in equity capital off of the big banks — something they desperately need to comply with the capital requirements of the Fed. The big banks plunged in share price along with the rest of the market on Christmas eve. Taking another phone call from Mnuchin is likely going to be avoided like the plague by the titans of finance.

It wasn’t just the general public that was frightened by Mnuchin’s inquiry about liquidity on Wall Street – the headline grabbing concern that dominated the news in the Wall Street crash of 2008. It was also sophisticated players across Wall Street who were aware that the Financial Stability Oversight Council (F-SOC) had just met four days prior to Mnuchin’s weird phone calls to the banks. F-SOC is the body that was created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to make sure that there weren’t any more surprise blowups on Wall Street that were large enough to threaten the U.S. financial system. Mnuchin chairs that body and it consists of every Federal regulator of Wall Street banks and their stock market operations.

Although minutes of F-SOC meetings are released on a delayed schedule, we know who attended the December 19 meeting and at least what was said in the public portion of the meeting because there is an official video available at the Treasury’s website. Mnuchin can be seen sitting between Jay Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve, and Jay Clayton, Chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission, ostensibly two of the most plugged-in regulators of Wall Street. One or the other might have whispered in Mnuchin’s ear before or after the meeting if there was any evidence of liquidity risks on Wall Street. That Mnuchin felt the need to personally canvass the banks by phone call just four days later led Wall Street traders to conclude that the regulators remain in the dark much as they were in the leadup to the Wall Street implosion of 2008 or that Mnuchin had heard a scary rumor in the intervening four days.

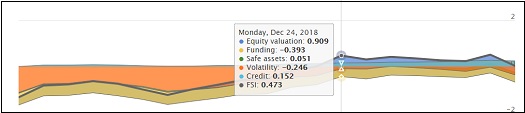

What also may have raised some alarm bells is a chart that is maintained by the Office of Financial Research (OFR). This agency was also created under the Dodd-Frank legislation. It’s part of the Treasury Department and its mission is to promote “financial stability by delivering high-quality financial data, standards, and analysis for the Financial Stability Oversight Council and the public.”

One of the charts the OFR updates regularly is the Financial Stress Index. That index is computed after the close of each trading day and is meant to provide a daily snapshot of stress in global financial markets. The Financial Stress Index includes five categories of indicators: credit, equity valuation, funding, safe assets and volatility and illustrates stress contributions from three regions: United States, other advanced economies, and emerging markets.

When the Index line is at zero it means that stress is at normal levels. When the line travels into negative territory, it means that stress is at lower than normal levels. What happened in December is that the index line began to crawl above the negative and zero level range for the U.S. region. (See chart below.) Of particular note, the reading on “credit,” was advancing above the zero level. Credit is defined by the OFR as “measures of credit spreads, which represent the difference in borrowing costs for firms of different creditworthiness. In times of stress, credit spreads may widen when default risk increases or credit market functioning is disrupted. Wider spreads may indicate that investors are less willing to hold debt, increasing costs for borrowers to get funding.”

While the moves in December were minute compared to 2008, Mnuchin may have wanted to shift any future blame to what he was told by the bank CEOs and be able to offer a defense that he reached out to them and was misled.