By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: November 8, 2017

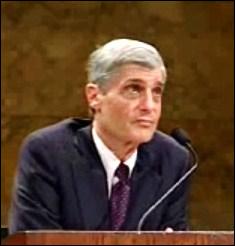

According to the now publicly available transcript of the testimony that former U.S. Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin gave before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) on March 11, 2010, he was not put under oath, despite the fact that the bank at which he had served as Chairman of its Executive Committee for a decade, Citigroup, stood at the center of the financial crisis and received the largest taxpayer bailout in U.S. history.

The fact that Rubin was not put under oath might have had something to do with the fact that he showed up with a team of six lawyers from two of the most powerful corporate law firms in America: Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and Williams & Connolly. One of Rubin’s lawyers from Paul, Weiss was Brad Karp, the lawyer who has gotten Citigroup out of serial fraud charges in the past.

As one reads the transcript, it becomes alarmingly apparent that a man making $15 million a year at Citigroup for almost a decade has not involved himself in very many intricate details of how the firm is being run or has a very selective memory. (Rubin gave up his $14 million annual bonus when the bank was blowing up during the financial crisis but kept his $1 million salary. According to widely circulated estimates, Rubin’s total compensation for his decade at Citigroup was over $120 million, for a job which he concedes included no operational role and with just two secretaries reporting to him.)

To many of the questions posed by Tom Greene, Executive Director of the FCIC, Rubin responded “I don’t remember.” Rubin used that phrase 41 times during the interview.

At one point, Rubin’s own lawyer, Brad Karp, appears to nudge Rubin on his failing memory. Greene asks Rubin if he attended a tutorial for the Board of Directors on September 17, 2007 on the risk environment. Rubin answers as follows: “It is interesting. I don’t remember either going or not going.” Karp then says to Rubin: “Bob, they have the minutes of this meeting.”

On matters big and small, Rubin simply couldn’t remember – despite the fact that many of the meetings and events under scrutiny had taken place less than three years prior and came at a critical time for this global bank.

Six months after Rubin testified before the FCIC, the Commission’s legal staff sent a Memorandum to the FCIC Commissioners recommending that Rubin, Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince and CFO Gary Crittenden be referred to the Department of Justice for further investigation. The September 12, 2010 memo reads as follows:

“The Securities and Exchange Commission recently concluded a $75 million civil settlement with Citigroup, its former chief financial officer and the head of investor relations arising from affirmative statements to the markets in 2007 that the company had only $13 billion in subprime exposure when, in fact, the company ultimately disclosed $55 billion in subprime exposure.

“The SEC’s complaint, filed in conjunction with the settlement, does not name the CEO, the chair of the Executive Committee of the Board of Directors, other members of the Board who were briefed on these exposures or the president of the firm’s Citi Markets and Banking unit, Citigroup’s investment bank, even though they all were aware of this information well before it was disclosed to the public.

“Based on FCIC interviews and documents obtained during our investigation, it is clear that CEO Chuck Prince and Robert Rubin, chair of the executive committee of the Board of Directors knew this information. They learned of the existence of the super senior tranches of subprime securities and the liquidity puts no later than September 9, 2007.

“On October 15, 2007, the same day markets were told that Citi’s subprime exposure amounted to $13 billion, members of the Corporate Audit and Risk Management Committee of the Board were advised that: ‘The total sub-prime exposure in Markets and Banking was $13bn with an additional $16bn in Direct Super Seniors and $27bn in Liquidity and Par Puts.’ This information was shared with other members of the Board of Directors.

“Two weeks later, on November 4, 2007, after a steep decline in subprime valuations, Citigroup announced that it had subprime exposures amounting to $55 billion; the value of these assets had declined by $8 to $11 billion and CEO Chuck Prince had resigned.

“Based on the foregoing, the representations made in the October 15, 2007 analysts call appear to have violated SEC Rule 10b-5, which makes it unlawful for ‘any person, directly or indirectly’ using any means of interstate commerce to ‘omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading’ in connection with ‘the purchase or sale of any security.’

“The SEC’s civil settlement ignores the executives running the company and Board members responsible for overseeing it. Indeed, by naming only the CFO and the head of investor relations, the SEC appears to pin blame on those who speak a company’s line, rather than those responsible for writing it.

“The former CEO, Mr. Prince, the former chairman of the Board, Mr. Rubin, and members of the Board may have been ‘directly or indirectly’ culpable in failing to disclose material information to the markets in violation of section 10b-5 of the 1934 Act.

“In addition, section 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires the CEO and the CFO to certify that annual and quarterly reports do ‘not contain any untrue statement…or omit to state a material fact.’ In carrying out this certification obligation, the ‘signing officers’ are responsible for establishing ‘internal controls’ that ‘ensure that material information…is made known’ to the officers during the time they are preparing the report.

“Although financial statements were routinely signed by the CEO and the CFO during the lead up to Citigroup’s ultimate disclosure of $55 billion in subprime exposure, internal controls were facially inadequate. As noted in a Federal Reserve Board report,

‘…there was little communications on the extensive level of subprime exposure posed by Super Senior CDSs, nor on the sizable and growing inventory of non-bridge leveraged loans, nor the potential reputational risk emanating from SIVs which the firm either sponsored or supported. Senior management, as well as the independent Risk Management function charged with monitoring responsibilities, did not properly identify and analyze these risks in a timely fashion.’

“Since the CEO and CFO are responsible under the Act for accurate quarterly and annual reports, as well as the adequacy of the risk management systems needed to make those reports accurate, referrals for violations of section 302 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act appear warranted.”

More than one year ago, Senator Elizabeth Warren sent detailed letters to the Inspector General of the Department of Justice and to then FBI Director James Comey, asking for a full disclosure of what had happened to these and other referrals made to the Department of Justice by the FCIC, since the DOJ brought no related prosecutions.

To date, the public remains in the dark on this matter.

Editor’s Note: Pam Martens, Editor of Wall Street On Parade, worked for two large Wall Street firms for 21 years. From 1996 through 2001, Martens challenged Wall Street’s private justice system in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York and at the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. Simultaneously, she also challenged a Citigroup unit’s employment practices. Brad Karp represented the Citigroup unit in the matter.

Related Articles:

Is the New York Fed Too Deeply Conflicted to Regulate Wall Street?

Relationship Managers at the New York Fed and Citibank: The Job Function Ripe for Corruption

Sealed, Redacted and Censored: Saving Citigroup, Killing America