By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: August 14, 2017

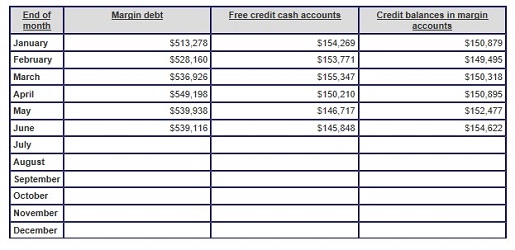

According to the latest data from the New York Stock Exchange, margin debt has hit new peaks four times this year, starting with a new record of $513 billion in January; $528 billion in February; $536.9 billion in March; and reaching a whopping $549 billion in April. The most recent reading for June shows a decline to $539 billion – but that is still an increase of 64 percent from the margin level of January 2008, the year of the epic financial crash on Wall Street.

Spiraling margin debt, where investors pledge securities at their brokerage firm to obtain a loan, typically to buy more securities, is frequently associated with stock market crashes. The dot.com bust followed a margin buying binge in 1999 and early 2000. Margin debt exploded from $153 billion in January 1999 to $278.5 billion by March of 2000, according to data from the New York Stock Exchange archives.

Loans using securities as collateral may be even more dangerous this time around. According to an enforcement action filed by the Massachusetts Securities Division on October 3, 2016, brokerage firms may be pushing securities based loans on their clients for purposes of mortgage funding, tax liabilities, weddings, and graduations. The enforcement action was brought against Morgan Stanley, the behemoth brokerage firm that gobbled up Smith Barney brokers, but the charges include an interesting statement from a former Morgan Stanley broker that suggests that another giant brokerage firm, Merrill Lynch, is offering similar loans. The statement from the broker reads:

“Morgan Stanley told our office during the end of February [2015] and beginning of March to pitch this product to all its customers. Management said they were doing this to keep up with its major competitor, Merrill Lynch, who was already offering express credit lines. They told us that there was big money to be made by having our customers take out credit since the variable interest rate was profitable to the company and they could just sell out of the customers positions if the customer failed to make the payment. They told us to call our customers to tell them that they could use the credit line to buy a house, pay for a home improvement project, buy a car and/or pay for school, etc. They asked us regularly how many people we had put in these products and used measurement tools to compare us amongst our peers. I did not feel comfortable recommending every customer establish a credit line because I felt that my role as a Financial Advisor and Fiduciary was to help customers save and make money and not go into bad debt.”

Offering securities based loans for purposes other than trading is not illegal if the full set of risks are disclosed and there are not inherent conflicts of interest. According to the Massachusetts Securities Division enforcement action, Morgan Stanley ran a sales contest to promote the loans and offered business development incentives to brokers of $1,000 for 10 loans; $3,000 for 20 loans; and $5,000 for 30 loans. The incentives apparently created excitement, with one broker responding in an email: “Game on!”

The loans were internally called PLAs (Portfolio Loan Accounts). According to the enforcement action, prior to the sales contest, 9 percent of Morgan Stanley’s Wealth Management clients had a securities based loan. By the third quarter of 2015, that figure had grown to 15 percent.

Morgan Stanley initially denied they had done anything wrong when the enforcement action was filed on October 3, 2016. By April of 2017, Morgan Stanley settled the matter by paying $1 million.

In 2015, the self-regulatory agency, FINRA, fined UBS for failures related to loans backed by securities collateral and ordered $11 million in restitution to 165 customers.

In a 2015 white paper by Paul Meyer of the Securities Litigation and Consulting Group, Meyer explains how the brokerage firms are framing the narrative around these kinds of loans:

“UBS, for example, extols the wisdom of ‘borrowing with a vision for your future’ and ‘maximizing the power of your invested assets.’ Morgan Stanley portrays borrowing as a way to ‘unlock the value of [the customer’s] portfolio.’ It claims that borrowing ‘puts the value of [the customer’s] assets to work.’ Merrill Lynch tells clients that borrowing money will ‘keep [their] investment strategy on track.’ After reading these characterizations of borrowing, a customer cannot not be blamed for concluding that he is imprudent if he is not borrowing against his portfolio.”

Meyer spells out the multiple risks associated with these loans, including the following:

“Unlike home mortgages or car loans, which require the borrower to make a monthly payment, most SBLs [securities based loans] simply add each month’s interest charge to the loan balance, thus compounding the interest expense. In addition to the financial risks, SBL borrowers have no protection from actions taken by broker-dealers to preserve their collateral. Loan accounts are susceptible to forced liquidation at unfavorable prices because, as the value of the securities declines, the borrower must either deposit additional collateral (which he often does not have) or sell multiples of the amount of his margin call. Furthermore, the broker can effect these sales without contacting or seeking the permission of the borrower. The broker can even choose unilaterally which securities it wishes to sell. A customer with no means of meeting margin calls other than by selling the collateral is generally not suitable for an SBL.”