By Pam Martens: December 12, 2013

This month marks the fifth anniversary of Bernard Madoff shocking the world by confessing to running a Ponzi scheme that was eventually tallied up to represent $17 billion in actual losses and $65 billion in paper losses – fictitious amounts shown on customer statements. It may also mark another ignoble first – the first time a Wall Street bank is criminally charged by the U.S. Department of Justice.

This month marks the fifth anniversary of Bernard Madoff shocking the world by confessing to running a Ponzi scheme that was eventually tallied up to represent $17 billion in actual losses and $65 billion in paper losses – fictitious amounts shown on customer statements. It may also mark another ignoble first – the first time a Wall Street bank is criminally charged by the U.S. Department of Justice.

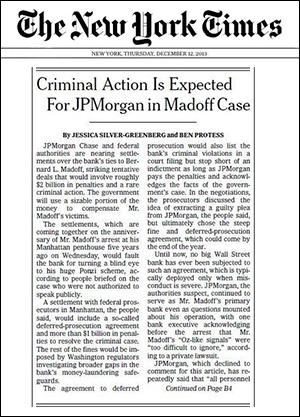

The Trustee in charge of recovering funds for victims of Madoff’s decades-long Ponzi scheme, Irving Picard, may have forced the hand of the U.S. Department of Justice to bring criminal charges against JPMorgan Chase for the banks’ enablement of the fraud. The New York Times is reporting on its front page today that criminal charges against JPMorgan and a deferred prosecution agreement related to its actions in the Madoff case may be announced before the end of this month by the Justice Department, together with a $1 billion penalty. Other Federal agencies may impose additional monetary penalties for broader lapses in money laundering controls at the bank.

While the actual charges may be coming from the Justice Department,as Wall Street On Parade has previously reported, it is Picard who has exquisitely presented JPMorgan’s wrongdoing in a manner easily understandable to the public. Last month Picard asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review an appellate court’s ruling that would bar him from suing JPMorgan and other banks for aiding the Madoff fraud in order to recover additional funds for victims. In his petition for review, Picard filed a scorching outline of his case against JPMorgan.

Picard told the Supreme Court that JPMorgan stood “at the very center of Madoff’s fraud for over 20 years.” Picard bases this claim on his lower court filing that showed JPMorgan was well aware that Madoff was claiming to invest tens of billions of dollars in a strategy that involved buying large cap stocks in the Standard and Poor’s 500 index while simultaneously hedging with options. But the Madoff firm’s primary bank account at JPMorgan, which the bank had intimate access to review for over 20 years, was devoid of evidence of stock or options trading.

The petition to the Supreme Court reads: “As JPM [JPMorgan] was well aware, billions of dollars flowed from customers into the 703 account, without being segregated in any fashion. Billions flowed out, some to customers and others to Madoff’s friends in suspicious and repetitive round-trip transactions. But in the 22 years that JPM maintained the 703 account, there was not a single check or wire to a clearing house, securities exchange, or anyone who might be connected with the purchase of securities. All the while, JPM knew that Madoff was using the account to run an investment advisory business with thousands of customers and billions under management and knew that Madoff was using its name to lend legitimacy to his enterprise…”

Picard told the Court that employees inside JPMorgan were well aware of the suspicions surrounding Madoff. Its own Chief Risk Officer, John Hogan, had warned his colleagues 18 months prior to Madoff’s revelation of his Ponzi scheme that “there is a well-known cloud over the head of Madoff and that his returns are speculated to be part of a ponzi scheme.”

In a lower court lawsuit, Picard wrote: “Evidence of Madoff’s fraud permeated every facet of JPMC [JPMorgan Chase]. It ran from the Broker/Dealer Group, where BLMIS [Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC] maintained a bank account that no one honestly could have believed was serving any legitimate purpose, to Equity Exotics, where JPMC learned of the red flags inherent in BLMIS’s investment strategy, to JPMC’s London office, which learned that individuals might be laundering money through BLMIS feeder funds, to the Private Bank, which maintained intimate relationships with one of BLMIS’s largest customers, to Treasury & Security Services, which was responsible for investing the balance of the 703 Account in short-term securities.”

Not only did JPMorgan provide the bank account through which Madoff perpetrated his decades-long fraud, but JPMorgan, despite its serious suspicions, invested over $250 million of its own money with Madoff feeder funds while it simultaneously created structured investment products that allowed its own investors to make leveraged bets on the returns of the feeder funds invested with Madoff.

In September 2008, just two months before Madoff would confess to running an unprecedented investment fraud, JPMorgan conducted a new round of due diligence and decided it was time to get out of its $250 million investment involving the feeder funds to Madoff.

The following month, on October 28, 2008, JPMorgan Chase sent a “suspicious activity report” not to its U.S. regulators but to the United Kingdom’s Serious Organized Crime Agency (SOCA). The document reads:

JPMorgan’s “concerns around Madoff Securities are based (1) on the investment performance achieved by its funds which is so consistently and significantly ahead of its peers, year-on-year, even in the prevailing market conditions, as to appear too good to be true – meaning that it probably is; and (2) the lack of transparency around Madoff Securities’ trading techniques, the implementation of its investment strategy, and the identity of its OTC option counterparties; and (3) its unwillingness to provide helpful information. As a result, JPMCB has sent out redemption notices in respect of one fund, and is preparing similar notices for two more funds.” No such warning was ever given to a U.S. regulator.

Because JPMorgan was still on the hook to pay the leveraged returns on the structured investments tied to the performance of Madoff funds that it had sold to investors, the Trustee expressed the belief that by redeeming its own $250 million hedge on this payout, JPMorgan demonstrated further evidence of its knowledge of the Madoff fraud.

Madoff pleaded guilty to the fraud and is serving a 150-year sentence in Federal prison. A criminal trial involving five of his employees is currently ongoing in Manhattan. All five employees have pleaded not guilty.