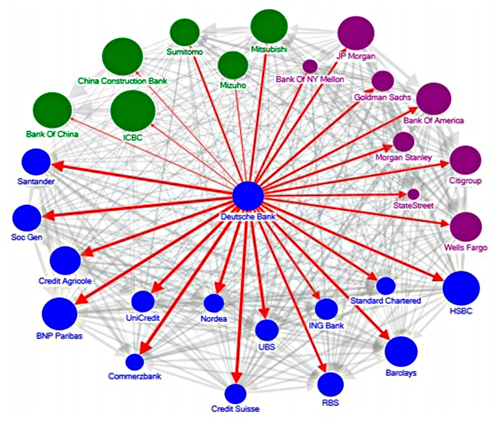

Systemic Risk Among Deutsche Bank and Global Systemically Important Banks (Source: IMF — “The blue, purple and green nodes denote European, US and Asian banks, respectively. The thickness of the arrows capture total linkages (both inward and outward), and the arrow captures the direction of net spillover. The size of the nodes reflects asset size.”)

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: April 16, 2019 ~

According to today’s New York Times, Democrats now in charge of the House Intelligence and Financial Services Committees, have issued subpoenas to Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Citigroup, related to the President’s finances and/or Russian money laundering.

We’d like to suggest that while that may well be a fruitful avenue of inquiry (see Russian Bank Chairman Met with Kushner, Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase), it does not rise to the level of national security risk posed by the derivative interconnectedness of those same banks. The President’s approximate $300 million in loans from Deutsche Bank and its ties to Russian money laundering, pales in comparison to trillions of dollars in interconnected derivative exposure of these same banks.

Americans saw what can happen when Congress ignores repeated red flags about derivatives. From 2008 through 2010 when derivatives and subprime debt imploded the U.S. financial system, millions of Americans lost their jobs, millions more lost their homes to foreclosure, and U.S. taxpayers were stuck with the greatest Wall Street bailout in U.S. history. The country is still struggling to recover from that period with the greatest wealth inequality since the 1920s and an unprecedented and ballooning national debt, much of which went to stimulate subpar growth left by the ravages of the so-called Great Recession – which many Americans feel was really the Great Wealth Transfer to Wall Street.

What the House Intelligence and Financial Services Committees should also be subpoenaing pronto is derivative counterparty exposure at each of those four banks, as well as at Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. Americans need to know right now, not after the next financial crash, how much derivative exposure U.S. banks have to Deutsche Bank, to each other, and to other foreign banks, hedge funds, etc.

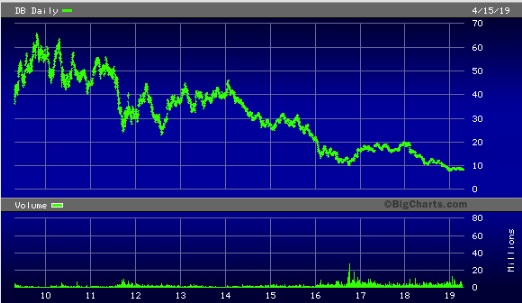

As the chart below indicates, Deutsche Bank’s stock has lost 85 percent of its market value over the past decade. As of this morning, it’s trading at $8.75 versus a $60 handle in 2009. That gives it a common equity market cap of $17.86 billion.

Deutsche Bank’s shrinking market cap stands in stark contrast to its mountain of derivatives, which its 2017 annual report put at €48 trillion notional. That report also indicated that 28 percent of its derivatives were not being centrally cleared but were bilateral contracts between it and another party. At the time, that translated into approximately 15.28 trillion U.S. dollars.

Opaque bilateral derivative contracts or over-the-counter derivative contracts obscure from regulators and thus from Congress where the next ticking time bomb is located in our financial system. It was the lack of exchange-traded derivatives and properly capitalized central clearing platforms for derivatives that resulted in the giant U.S. life insurer, AIG, requiring a $185 billion backstop from the U.S. taxpayer in 2008. It is also why Lehman Brothers imploded in short order in the 2008 Wall Street crash.

According to an article by GuyLaine Charles in the New York Business Law Journal in 2009, Lehman Brothers at the time of its bankruptcy filing in September 2008 was a counterparty to 930,000 derivative contracts and “over 190,000 of these contracts had not been terminated by their counterparties and remained outstanding.”

That one sentence alone explains the unprecedented level of financial panic that gripped markets in 2008. Because of the opacity of these over-the-counter derivative contracts, no one knew which institutions had the greatest exposure to Lehman and which bank would be next to fail. Demands for collateral were made all over the street; credit seized up; and banks stopped lending to each other — leaving the Fed and the U.S. taxpayer as the lender of last resort.

Today, we have another such perfect storm brewing. According to a 2016 report from the International Monetary Fund, Deutsche Bank is heavily interconnected financially to Wall Street banks, including JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and Bank of America. (See chart above from the IMF report.) Derivatives, most assuredly, play a big role in those interconnections.

When Greg Lippmann (the Deutsche Bank derivatives salesman who inspired the character played by Ryan Gosling in The Big Short movie) was interviewed by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, he had this to say about derivative counterparty risk:

“So in 2007, it was very simple for us to buy protection from whoever we wanted. But then that was very simple for the managers to get protection because it became a robust market where it wasn’t so much in the early part of 2006.

“I mean, I didn’t like it because then I had to write all these tickets, right, because now I have exposure to all the other investment banks, right. So let’s even pretend that it was just — that I did half, and the other half were other people. So if Deutsche Bank has 5 billion of CDOs, two-and-a-half billion are with me, and then I have two-and-a-half billion of exposure to other investment banks where I’m intermediating between them and our CDO.

“When it was done, I was told, ‘This is how you have to do it because it’s a lot easier to do it this way, and everybody’s doing it this way.’ But as it turned out, of course, when Lehman Brothers went under, all the sudden you had this situation where you thought you weren’t short. In our example, you thought that Lehman Brothers was short, and you were just intermediating. And, obviously, the converse was true as well. If I was short into a Lehman Brothers CDO, I thought I was short, and I wasn’t short because my counter-party disappeared.”

If Deutsche Bank were to “disappear” (as in file bankruptcy), could the U.S. have a replay of Lehman Brothers all over again? Congress owes it to the American people to examine this potentiality now – not sit back and hope it doesn’t become a reality.

On August 14 of last year, the Italian business newspaper, Il Sole 24 Ore, published an interview with Stuart Lewis, the Chief Risk Officer of Deutsche Bank. Lewis didn’t want to talk about the notional (face amount) of derivatives the bank had exposure to. He wanted to talk about cash flows. This is what he told the newspaper:

“Gross notional derivative exposure is no reflection of credit or market risk. Let’s look at the flows. It is important to start by saying that derivatives are cash flows on underlying assets. So we never refer to derivatives portfolios in terms of the notional value of the underlying assets, what counts is the cash flow. The derivatives risk is made of the asset price sensitivity, the mark-to-market of our positions and the counterparty risk: assessing the probability that the counterparty of a derivative is not able to meet its obligations. The gross size of our derivatives trading portfolio, at market value according to European accounting standards IFRS, is made of the present value of the future cash flows: €348 billion is the flow owed to us by our counterparties and €276 billion is the flow that DB owes to the counterparties. The netting of these two opposite flows brings it down to a net derivatives exposure of €72 billion.”

Okay, so let’s talk cash flows not €48 trillion notional in derivatives. If Deutsche Bank, which currently has a common equity market cap of $17.86 billion and it owes €276 billion (approximately 311.9 billion U.S. dollars) to its counterparties, how is that not a big problem?

In the interview with Il Sole 24 Ore last August, Lewis was also asked about those pesky, mark-to-myth Level 2 and Level 3 assets on Deutsche Bank’s books. Lewis said this:

“Let’s make one thing clear. Level 2 and Level 3 assets are not a description of the riskiness of the assets but a description of the observability of the fair value that you attach to the asset. It is a matter of accounting. Level 1 assets have quoted prices in active markets, so it is easy to see how they trade and perform to assess their fair value. Exchange traded derivatives, like futures and traded options, are in this category. Level 2 assets pricing is determined by reference to similar instruments traded in active markets, comparable assets on observable market data. Many OTC derivatives fall into this category, and also many CDOs. The Level 3 assets prices cannot be determined directly with market-observable information. However, Level 3 assets are traded. These are the complex OTC derivatives, illiquid ABS, CDOs and loans. Now the size: our Level 2 assets amount to 495 billion, our Level 3 assets are 22 billion.”

If this situation doesn’t deserve the attention of Congress, we don’t know what would.