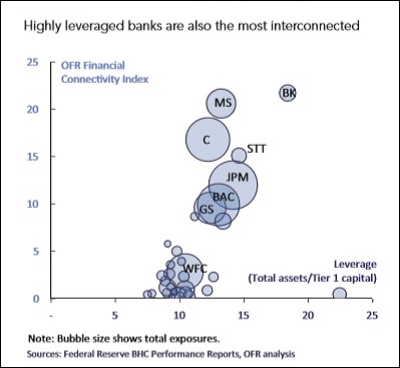

Wall Street Mega Banks Are Highly Interconnected: Stock Symbols Are as Follows: C=Citigroup; MS=Morgan Stanley; JPM=JPMorgan Chase; GS=Goldman Sachs; BAC=Bank of America; WFC=Wells Fargo.

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: January 20, 2016

Market action since the Federal Reserve’s first, in a promised series, of rate hikes on December 16 to put the U.S. back on a path of “normalization” and end its seven-year zero-interest-bound policy has reminded us of that line from the movie “Six Days Seven Nights.” Actress Anne Heche goes on what was supposed to be a pre-honeymoon vacation to instead experience a plane crash, be held hostage, and fight for her very survival. At one point she says words to the effect: I don’t know how much more of this vacation I can take. Investors might be forgiven for feeling the same way about the Fed’s idea of “normalization.”

What U.S. investors woke up to this morning was another day of market hell. Futures on the Dow Jones Industrial Average were showing a loss of more than 300 points; Europe and Asia stocks had been pummeled overnight; and domestic crude oil (West Texas Intermediate) had sunk to a new 12-year low under $28 a barrel. According to Bloomberg News, on a global basis, as measured by the MSCI All-Country World Index, stocks have now lost over $15 trillion since May.

As for the Fed’s ability to get interest rates moving back up, the 10-year U.S. Treasury note which closed at a yield of 2.29 percent on the day of the Fed’s rate hike announcement on December 16, has this morning broken below 2 percent to trade at a yield of 1.97 percent.

Business news pundits in the meantime are attempting to find a culprit to explain the carnage. China is getting most of the finger-pointing for its slowing economy bogged down with debt. It can no longer be the global engine of growth since it no longer wants or needs or can afford the glut of industrial commodities being produced by developing countries. This has led to a collapse in commodity prices.

Without the exports to China, developing countries and corporations inside those countries that issued U.S. dollar-denominated debt now find themselves in the precarious position of having shrinking export profits and a currency that has lost value versus the U.S. dollar. That effectively has increased the amount of debt they owe to U.S. banks which has, in turn, raised worries among investors about the potential for unreserved loan losses at the mega Wall Street banks.

Two Wall Street banks, Citigroup and Morgan Stanley, have seen their share prices decline by more than 30 percent since July. JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Bank of America have also experienced double-digit declines in the same period.

The hubris of incompetent regulation of the behemoth Wall Street banks, which Congress not only failed to tame after the 2008 crash but allowed to grow much larger in terms of systemic risk, has now come home to roost. If these banks own up to losses and boost loan loss reserves for what is inevitably coming, their share prices will dive further. If they don’t, markets will assume they’re lying and guess at what their share price should be, potentially hurting them even more.

In fact, the Wall Street Journal carried an article last week which suggests investors already don’t trust what they’re hearing from the banks. In a “Heard on the Street” column John Carney writes that Citigroup “is now trading at a nearly 40% discount to book value.” Book value means the total assets minus the total liabilities of the company. Such a huge discount from the stated book value suggests that investors believe some of those Citigroup “assets” may be impaired. Where would they get such an idea? This is what the former head of the FDIC, Sheila Bair, had to say about Citigroup’s situation during the 2008 crash in her book Bull by the Horns:

“By November, the supposedly solvent Citi was back on the ropes, in need of another government handout. The market didn’t buy the OCC’s and NY Fed’s strategy of making it look as though Citi was as healthy as the other commercial banks. Citi had not had a profitable quarter since the second quarter of 2007. Its losses were not attributable to uncontrollable ‘market conditions’; they were attributable to weak management, high levels of leverage, and excessive risk taking. It had major losses driven by their exposures to a virtual hit list of high-risk lending; subprime mortgages, ‘Alt-A’ mortgages, ‘designer’ credit cards, leveraged loans, and poorly underwritten commercial real estate. It had loaded up on exotic CDOs and auction-rate securities. It was taking losses on credit default swaps entered into with weak counterparties, and it had relied on unstable volatile funding – a lot of short-term loans and foreign deposits. If you wanted to make a definitive list of all the bad practices that had led to the crisis, all you had to do was look at Citi’s financial strategies…What’s more, virtually no meaningful supervisory measures had been taken against the bank by either the OCC or the NY Fed…Instead, the OCC and the NY Fed stood by as that sick bank continued to pay major dividends and pretended that it was healthy.”

At 9:52 a.m. this morning in New York, Citigroup’s stock was trading with a loss of 3.71 percent after trading at a new 12-month low of $40.35. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America also traded at new 12-month lows this morning.

Despite its stress tests and living wills and enhanced capital requirements and legions of bank examiners, the Federal Reserve can’t seem to get its mind around the meaning of “systemic” – as in Global Systemically Important Banks or G-SIBs.

Here’s the Random House dictionary definition to help out the Fed:

“Pertaining to or affecting the body as a whole…absorbed and circulated by a plant or other organism so as to be lethal to pests that feed on it.”

The Dodd-Frank reform legislation created the Office of Financial Research (OFR) within the U.S. Treasury Department to provide meaningful research to the Financial Stability Oversight Council (F-SOC) – where every major regulator of Wall Street banks has a seat, including the Fed.

In February of last year, OFR published a report clearly demonstrating that if one of these mega Wall Street banks got into trouble, all hell was going to break loose, because they are highly interconnected. (See chart above.) Too bad Congress, the President and the Fed paid no heed.