By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 16, 2015

By Pam Martens and Russ Martens: December 16, 2015

If the U.S. government issued a warning yesterday that there was a credible threat of a new terrorist attack from a foreign terrorist, we can guarantee you that it would have made front page headlines. What the U.S. government did instead yesterday was to issue a formal warning that the prospects for a new financial crisis have grown, and, in one area, are at an “historically elevated level.”

Since the financial crisis of 2007-2009 did more economic damage to the U.S. than all terrorist attacks combined and will have a devastating impact on the standard of living of the next generation, one would think this new financial warning would have been worthy of a mention on the front pages of mainstream newspapers. And yet, we could find no mention in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Washington Post, etc. (To their credit, the Wall Street Journal and Reuters did write about the findings.)

What might explain the hesitation to carry the story by the major dailies is the contradictory nature of the material released by the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Financial Research (OFR). That’s the body created under the Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation of 2010 to keep the Financial Stability Oversight Council (also created under Dodd-Frank) informed on a timely basis to rising threats to financial stability in the U.S.

The OFR report listed a litany of hair-raising threats to financial stability but then bizarrely concluded: “Overall, threats to U.S. financial stability remain moderate….”

Rational readers of the report must conclude that when financial data turns unprecedented and “historic” in a significantly negative way, it can’t be a “moderate” concern. For example, the report advises the following:

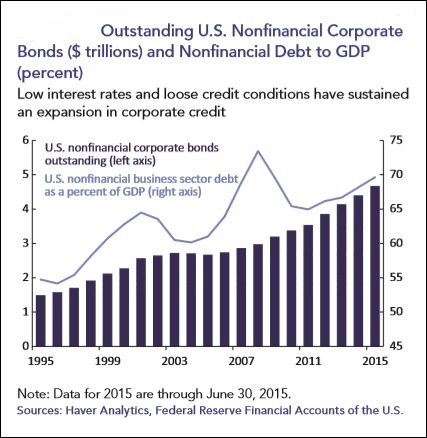

“Signs of excess in U.S. nonfinancial corporate credit markets have persisted since our last report. Rapid debt growth continued, and the ratio of nonfinancial business debt to GDP reached a new post-crisis high. Balance sheet leverage, particularly for highly-rated firms, has continued to rise as new debt continued to increase and earnings fell. The rise in leverage is most pronounced among more vulnerable companies — firms with already elevated debt levels or weak repayment capacity.”

Corporate debt to GDP reaching a “new post-crisis high” in a vulnerable economy does not sound like a “moderate” threat to us. Our major trading partners (Canada and China) are experiencing a significant slowdown, the rise in the U.S. dollar is impeding our ability to export our way out of subpar growth, and the Fed is signaling that it plans to raise rates. (We’ll know the outcome of that Fed “signaling” at 2 p.m. today.)

On the matter of how a Fed rate hike might add to financial instability, the OFR report notes the following:

“Higher base interest rates and spreads induced by monetary tightening may create refinancing risks, expose weaknesses in heavily leveraged entities, and potentially precipitate a broader default cycle. The fact that U.S. nonfinancial business debt has expanded so rapidly since the financial crisis suggests that even a modest default rate could lead to larger absolute losses than in previous default cycles.”

Nothing in the above statement sounds like a “moderate” level of risk either. Less than a decade ago, the U.S. went through the worst economic disaster since the Great Depression. To keep the country from sinking into a full blown depression, the government engaged in both fiscal and monetary spending which has ballooned the national debt to $18.8 trillion and the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet to $4.5 trillion – two more unprecedented firsts in not a good way.

The public thought that the irresponsible debt binge that led to the last crisis would be followed by a debt liquidation cycle – creating the foundation for a stronger, more resilient U.S. economy. So what happened to the debt liquidation cycle? How did we end up in a situation where “even a modest default rate could lead to larger absolute losses than in previous default cycles.”

We have a growing suspicion that the bureaucratic juggernaut that Congress has built around Wall Street and its financial appendages is providing the illusion of monitoring risk while the actual risk is spiraling, once again, out of control. The Federal agencies monitoring Wall Street banks are as follows: the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the U.S. Treasury and its OFR, the Financial Stability Oversight Council, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and that list doesn’t even include the industry’s self-regulators like stock exchanges and FINRA.

And yet, with all of those monitors and tens of billions of dollars in costs for staff and studies, yesterday OFR said in its press release announcing the new report that:

“Financial activity and risks have migrated outside the regulatory perimeter, market liquidity appears to have become more fragile in recent years, and interconnections among financial firms and markets are evolving in ways not fully understood.”

“Not fully understood?” Americans should be protesting in the streets over that revelation. It is simply unacceptable for our government to have spent seven years since the epic financial collapse and have nothing better to tell taxpayers than it does not fully understand how our financial system works. Clearly, if it can’t be understood, it must be simplified. As we have warned for years, the Glass-Steagall Act is the only reliable means of ensuring a stable financial system. An ever growing number of regulators have been scratching their heads and staring into the abyss ever since Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999.

To illustrate just how insane the new Frankenbank Wall Street model is, the OFR report explains how the effort to bring transparency and financial stability to the hundreds of trillions of dollars of derivatives on the books of the FDIC-insured, deposit taking banks has worked out. The plan was to create central counterparties (CCPs) that would clear derivatives transactions and replace the opaque, over-the-counter process that was in place pre-crisis. The new plan went like this according to OFR:

“CCPs can reduce a firm’s exposure to individual counterparties and can mitigate overall credit risk through multilateral trade netting and imposing risk controls on clearing members.”

What has happened instead is that the Financial Stability Oversight Council has now designated five CCPs as themselves “systemically important” because, says the OFR: “The failure of a CCP could impose large losses on major financial firms and disrupt the operation of other parts of the financial system. The main risk to the solvency of a CCP is the failure of its members to meet payment obligations on the transactions they clear through the CCP.”

We seem to have traveled in a circle for seven years, arrived back at the same point we found ourselves at on September 15, 2008, and have nothing to show for it but a sprawling octopus of financial industry watchers – not watchdogs, mind you, just watchers.